How to choose a degree – putting it all together

It’s time. This is where you pull together all the information you have assembled to work out what you will be most likely to succeed at and which degrees will set you up to do good.

It’s time. This is where you pull together all the information you have assembled to work out what you will be most likely to succeed at and which degrees will set you up to do good.

I talked earlier about how at university you should probably pick more mathematical ‘hard’ subjects over more artsy ones and focus on getting a good degree class. This is pretty similar to conventional advice on choosing a degree. But I found a lack of practical step-by-step guides to picking the right degree for you. This guide gives you a structured way to gather all the relevant information and to make a decision on your degree. Without a structured process it’s easy to narrow down your options too fast, to ignore important evidence, and to apply your evidence inconsistently.

In my last post I looked at the role of degree choice for professional and academic careers. Now let’s branch out and look at the more general role of degree choice. This matters for people interested in Advocacy, Innovation, Improving as well as Earning to Give in non-professional careers. At this stage in our research, it seems that degrees in more quantitative subjects improve your employment prospects and your flexibility, which is important for making a difference. The next most important thing is to pick a degree you expect to do well in. But, again, we’ll be refining that view as we explore more of the evidence.

One of the most important early career decisions many people face is what to study at university. This is the first of a series of posts on degree choice intended for people who mean to go to university. Degree choice plays an important role in your ability to make a difference later in life. People probably don’t put enough effort into systematically thinking about degree choice. In this post I’ll look at the importance of degree choice for professional careers and academic careers. In the next post I look at the importance for general career choice.

Rob Wiblin and I interviewed Nick Bostrom, founding Director of the Future of Humanity Institute in Oxford, about his career and ways to do high impact research.

One huge barrier to making good career decisions is thinking too narrowly. There are just too many options, and too many different ways to compare them, to possibly hold all of this in our minds at once. But this means we could end up missing valuable options or important considerations. Why do we do this, and how can you broaden your options?

When people say that time is money, they mostly mean that you can earn money with your time. But it works both ways. In a previous post I discussed how we can spend money on a virtual assistant to save time. Here I will discuss some ways that you can spend money on goods or services to save you time.

Ben Gilbert’s an 80,000 Hours member who previously worked as a trader in the City, but now focuses his attention on the effective giving community and the development of charter cities. We met in Oxford to discuss his career, jobs in trading and his plans for making a difference in the future.

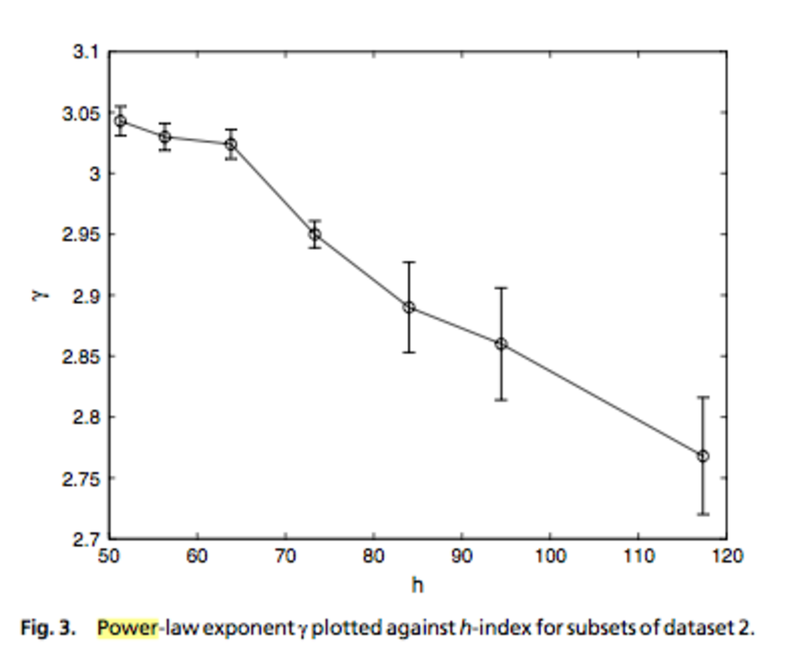

Why do the best researchers get almost all the attention? One factor is the Matthew effect, in which “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.” In this context, the Matthew effect means that the most accomplished researchers get increasing amounts of credit and attention.

Often when faced with a really difficult question, people “cheat” by opting to answer an easier but related one, without realising they’re doing it. Sometimes this is a helpful tactic, but it can be a huge source of error. Could you be doing this with your career decisions?

People often end up cheating and answering an easier question because the real question is so complex that they don’t even know how to go about answering it. What we’re aiming to do is provide you with the tools and guidance you need to answer the questions “Which career is right for me?” and “How can I make a difference in my career?”, so that you don’t need to cheat.

The power of persuasion for making a difference is often underappreciated. If you can convince just one other person to care about a cause as much as you, then you’ve easily doubled your impact. But people’s efforts at influencing others often aren’t as efficient as they could be. By stepping outside your circle of personal contacts and choosing a strategic approach, your time and influence can go ten or even a hundred times further.

Note: this post has been superseded by our job satisfaction page and supporting research page.

Many people aren’t as satisfied as they could be with their careers. This is a big problem: not only is the person less happy, they also end up making less difference in society. The even bigger problem is that people don’t seem to know what to do about this – how to find a job that they’ll find satisfying. There’s a lot of psychology research on happiness that could be really useful, but people don’t seem to be aware of it or at least aren’t applying it. So we decided to start collecting together the research that seems most useful to job satisfaction, and explaining how it applies to your career decisions.

You want to make a difference. This means being as successful as possible in whatever high-impact path you pursue. In recent posts, I raised a worry that we might overestimate our chances of success. But at the same time we don’t want to underestimate them: something we do have reason to think we’re better than average at something.

There are three ways to contribute to scientific progress. The direct way is to conduct a good scientific study and publish the results. The indirect way is to help others make a direct contribution. Journal editors, university administrators and philanthropists who fund research contribute to scientific progress in this second way. A third approach is to marry the first two and make a scientific advance that itself expedites scientific advances. The full significance of this third way is commonly overlooked.

It’s getting closer to Christmas, and we’re running out of time to get presents for friends and family. It can be hard to work out what presents people will actually enjoy. An increasingly popular option is to make a donation on behalf of someone else as a present. What’s the best way to do that? Does it involve goats? You might be interested in Giving What We Can’s gift cards that let you donate to the world’s most effective charities .

If you want to make a difference in your career, you need to think not just about which jobs have the most impact, but which jobs you’ve got the best chances of success in. This latter point can be easily neglected. It’s all very well working for an incredibly high impact cause, but if you do a rubbish job you won’t make much difference. Judging your chances of success is hard. Knowing the odds: the average person’s chances of success, is a good place to start.

Ben and I spoke with Anders Sandberg, a James Martin research fellow at the Future of Humanity Institute, about his career and how to make a difference through research. Here are some of the highlights!

Most people think they’re better than the average person: that they’re smarter, more likeable, more attractive. This tendency to think of ourselves as better than average is a well-established bias. But if we need to do this to feel better about ourselves, who cares? The problem is that we’ll also overestimate our chances of being successful. And if you want to work out where to make the most difference, you need to have a realistic idea of where your chances of success are best.

Microcredit has become one of the most popular ideas in charity. 2005 was named the Year of Microcredit.The microcredit charity Kiva has over 800,000 lenders, the highest possible rating from Charity Navigator, and was endorsed by Oprah… The 2006 Nobel Committee boldly claimed that microcredit “must play a major part” in ending global poverty.

Recently, however, criticism of microfinance has been growing. And that’s a good thing, because it’s far from proven that microfinance, on average, has any positive effects at all.

Paramedics appear to make good, fast decisions based on “gut feeling”: knowing what to do without knowing how you know. Along a similar vein, chess grandmasters are able to identify and decide on the best moves incredibly rapidly, moves which mediocre players may not even spot at all.

But this ability to make astoundingly accurate judgements in the blink of an eye isn’t limited to experts. We all do it every day: when we judge what some else wants from their facial expressions, or catch a ball without doing any complex physics calculation. How are these triumphs of intuition possible?