Max Roser on building the world’s first great source of COVID-19 data at Our World in Data

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published June 21st, 2021

Max Roser on building the world’s first great source of COVID-19 data at Our World in Data

By Robert Wiblin and Keiran Harris · Published June 21st, 2021

On this page:

- Introduction

- 1 Highlights

- 2 Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

- 3 Transcript

- 3.1 Rob's intro [00:00:00]

- 3.2 The interview begins [00:01:41]

- 3.3 Our World In Data [00:04:46]

- 3.4 How OWID became a leader on COVID-19 information [00:11:45]

- 3.5 COVID-19 gaps that OWID filled [00:27:45]

- 3.6 Incentives that make it so hard to get good data [00:31:20]

- 3.7 OWID funding [00:39:53]

- 3.8 What it was like to be so successful [00:42:11]

- 3.9 Vaccination data set [00:45:43]

- 3.10 Improving the vaccine rollout [00:52:44]

- 3.11 Who did well [00:58:08]

- 3.12 Global sanity [01:00:57]

- 3.13 How high-impact is this work? [01:04:43]

- 3.14 Does this work get you anywhere in the academic system? [01:12:48]

- 3.15 Other projects Max admires in this space [01:20:05]

- 3.16 Data reliability and availability [01:30:49]

- 3.17 Bringing together knowledge and presentation [01:39:26]

- 3.18 History of war [01:49:17]

- 3.19 Careers at OWID [02:01:15]

- 3.20 How OWID prioritise topics [02:12:30]

- 3.21 Rob's outro [02:21:02]

- 4 Learn more

- 5 Related episodes

The real story was the growth rate. [That’s] the key thing that you have to know in an outbreak of an infectious disease, and the focus wasn’t on the growth rate. And I was going mad. I just couldn’t believe how poor this reporting was.

Max Roser

History is filled with stories of great people stepping up in times of crisis. Presidents averting wars; soldiers leading troops away from certain death; data scientists sleeping on the office floor to launch a new webpage a few days sooner.

That last one is barely a joke — by our lights, people like today’s guest Max Roser should be viewed with similar admiration by COVID-19 historians.

Max runs Our World in Data, a small education nonprofit which began the pandemic with just six staff. But since last February his team has supplied essential COVID statistics to over 130 million users — among them BBC, the Financial Times, The New York Times, the OECD, the World Bank, the IMF, Donald Trump, Tedros Adhanom, and Dr. Anthony Fauci, just to name a few.

An economist at Oxford University, Max Roser founded Our World in Data as a small side project in 2011 and has led it since, including through the wild ride of 2020. In today’s interview, Max explains how he and his team realized that if they didn’t start making COVID data accessible and easy to make sense of, it wasn’t clear when anyone would.

But Our World in Data wasn’t naturally set up to become the world’s go-to source for COVID updates. Up until then their specialty had been in-depth articles explaining century-length trends in metrics like life expectancy — to the point that their graphing software was only set up to present yearly data.

But the team eventually realized that the World Health Organization was publishing numbers that flatly contradicted themselves, most of the press was embarrassingly out of its depth, and countries were posting case data as images buried deep in their sites, where nobody would find them. Even worse, nobody was reporting or compiling how many tests different countries were doing, rendering all those case figures largely meaningless.

As a result, trying to make sense of the pandemic was a time-consuming nightmare. If you were leading a national COVID response, learning what other countries were doing and whether it was working would take weeks of study — and that meant, with the walls falling in around you, it simply wasn’t going to happen. Ministries of health around the world were flying blind.

Disbelief ultimately turned to determination, and the Our World in Data team committed to do whatever had to be done to fix the situation. Overnight their software was quickly redesigned to handle daily data, and for the next few months Max and colleagues like Edouard Mathieu and Hannah Ritchie did little but sleep and compile COVID data.

In this episode Max explains how Our World in Data went about filling a huge gap that never should have been there in the first place — and how they had to do it all again in December 2020 when, eleven months into the pandemic, there was still nobody else to compile global vaccination statistics.

We also talk about:

- Our World in Data’s early struggles to get funding

- Why government agencies are so bad at presenting data

- Which agencies did a good job during the COVID pandemic (shout out to the European CDC)

- How much impact Our World in Data has by helping people understand the world

- How to deal with the unreliability of development statistics

- Why research shouldn’t be published as a PDF

- Why academia under-incentivises data collection

- The history of war

- And much more

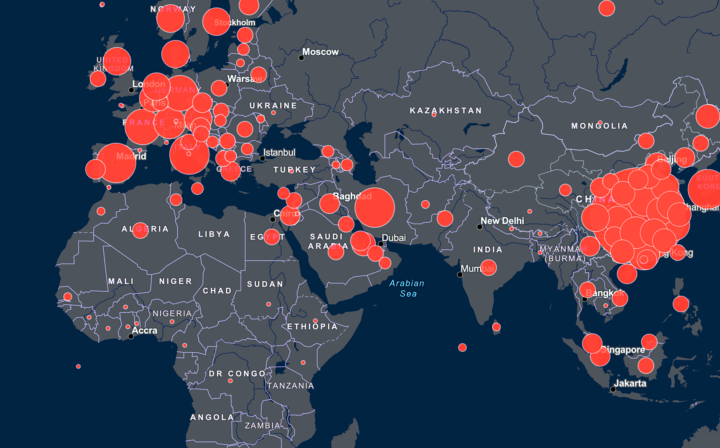

Final note: We also want to acknowledge other groups that did great work collecting and presenting COVID-19 data early on during the pandemic, including the Financial Times, Johns Hopkins University (which produced the first case map), the European CDC (who compiled a lot of the data that Our World in Data relied on), the Human Mortality Database (who compiled figures on excess mortality), and no doubt many others.

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris

Audio mastering: Ryan Kessler

Transcriptions: Sofia Davis-Fogel

Highlights

Our World In Data

Max Roser: The mission that we have is to present the research and data on the world’s largest problems so that we can find ways to make progress against those problems. That’s what we want to achieve. And then the way that we hope to achieve this is basically twofold: On the one hand, there are already lots of people who have this idea, that work on a big global problem, whether it’s a health issue, or a disease, or whether it’s getting kids into school and improving education. And for all of those people, we just want to serve the information in an accessible and understandable format. That’s really the key of that.

Max Roser: And then we also have this second part of the mission, where we would like to expand that community. Where I think lots of people are just very concerned about large global problems, but are very far away from the research and from the data. And so they have only a poor understanding of what the problems really are, how they compare in size, whether we are making progress or not, etc. And so we have this idea that many people are concerned, but don’t actually know that it’s possible to do something about these problems, and that there are ways forward. And so we try to encourage them and motivate them to see that it’s worth dedicating time, effort, even a career, possibly, to support this kind of work.

How OWID prioritise topics

Max Roser: One difference between our team and much of academia is that we are much more demand-driven. So while a lot of academics have this idea that they want to work on a particular project and hope for the best that someone picks it up, we try to speak a lot to the users that we have and hear what they see as gaps and where they see that something’s missing. And then try to respond to the demand that is there. That could also be journalists that we value, and we hear from a lot of experts what they would want to see. For example, last week I was having dinner with Will MacAskill, and he said there’s an internal document that’s basically his wishlist that’s growing and growing as he wants to see more research and data. And we take this into account, obviously.

Max Roser: Another key consideration is who the people on our team are and what kind of work they can contribute. For example, Saloni Dattani, who joined us very recently, is an expert in health issues, she cares a lot about mental health. I think that’s an aspect that is under-discussed on a global scale. And so she was the perfect fit to take on this project. And then another key consideration always is that we try to fill some niche where others often haven’t already done great work.

COVID-19 gaps that OWID filled

Max Roser: It’s shifted a bit. At the beginning, we had two projects that we were working on. It was very much also just explaining how to think about these numbers. So we wrote these explanations of what the case fatality rate is and how it’s different from the infection fatality rate, and in which ways these tool measures might differ. I know that lots of journalists were relying on these very basic explanations of the key metrics, and that became less and less important just because the media became better and better over the pandemic. Last February it wasn’t great, but I think now there have been really amazing journalists in many key outlets that do a great job. There was just a huge improvement. We did less and less of that.

Max Roser: And we did focus on the other job that we had of just cataloging the data, and that was bringing some of the existing international statistics together, the straightforward ones, cases and deaths, but then also increasingly things like excess mortality statistics, and hospitalization figures. Back in March, there were really several strengths to the work that we were doing on COVID. One was explaining the key metrics and helping readers to make sense of what the case fatality, the infection fatality rates are, how these two measures differ, how they might change over the course of an outbreak, how the amount of testing is impacting these metrics. And that was helpful for a lot of journalists at the time. We were in touch with many journalists, and then we did less and less of that because the journalism around COVID just hugely improved over time. It wasn’t great back in February, March last year, but it’s pretty awesome right now. There are lots of really great people.

Max Roser: Then another strand of the work was to compile these aggregate datasets on international statistics. We took the confirmed cases and confirmed deaths from the European CDC, but we then later compiled many more sources. We did the testing database, that was in our hands. We did aggregate the data on excess mortality. We compiled survey information from people’s opinions, and then much more recently, obviously, the vaccination data. And the key job there was, on the one hand, to produce a clean spreadsheet that other people could then rely on, that they could pull into their reporting — so big news organizations could just pull our .csv file every morning and then update all of their statistics on their outlets. And the other one was to build the tools that make it possible to explore the data right there on our site, because that’s something I think even the ECDC was struggling with. They made the data available, but the tools to then actually visualize the data and compare countries and understand the data, that wasn’t great. And it’s also not their job in a way. Right? So I think that’s fair.

Vaccination data set

Max Roser: I think the aspect that we haven’t spoken so much about is the vaccination dataset. And that’s honestly one that I really got wrong. I would have not expected somehow that there would be so much attention being paid to the vaccination dataset, and I would have also not expected that it would be on us to produce this dataset. And I was really wrong on both counts. The vaccinations started in December, and we were all tired. We were all looking forward to Christmas. And then Edouard was suggesting that we should probably compile the vaccination data, since the first person here in the U.K. was vaccinated just then. And I was like, “No, we’re not going to do this. This is just… It can’t be on us.” I was like, “I want to take some time off. I want to see my parents over Christmas. We’re not going to do that. And also surely someone will do it.” And then his point was like, “Well, no one is doing it yet. And also it’s something that’s going to be fine if we just do a weekly update.” That was the point that convinced me: “It’s going to be fine if we do a weekly update.” And then he started by himself. And obviously there was so much attention to it. I think at the beginning, it was just because of this story that Israel was vaccinating so much faster than everyone else, and there was this huge discrepancy. Lots of countries, again, struggle to make their data available. So there was much more focus on it.

Max Roser: And suddenly it became this really full-time job just for him. He was sitting in his apartment in Paris, producing this spreadsheet that everyone from The Economist, The Financial Times, The New York Times, the WHO, the U.S. CDC, everyone is relying on his figures. On the one hand, I think it should, again, not be the situation. On the other hand, I’m really proud of him pushing for that and building this dataset and informing the public about what’s going on with the global vaccination roll out.

Data reliability and availability

Max Roser: It’s a huge issue. And we touched on it earlier in the discussion, where I was mentioning that I think too many resources go into the analysis of often poor data, and too little resources are actually given to improve the data in the first place. And data from poor countries is one of those areas where we know that the data is often of poor quality. But that’s true for data across many sectors, even in rich countries. And it’s one of our key efforts in this work to find this balance, because we always live in a world with imperfect data. There’s no data that’s ever perfectly accurate, but we have to see where the data is actually able to tell us something about the world, and what we should know about the data to make sense of it, and where we should instead stay away from it. So it’s a massive concern. And just really at the heart of our work.

Rob Wiblin: Does that maybe imply that, in your work, less might be more? That perhaps trying to be really comprehensive and presenting lots of different pieces of data about all of the countries could end up replicating this unreliable data? And perhaps people would end up giving too much weight to data that they should mostly be ignoring. And perhaps you should just focus on a smaller range of numbers, the highest quality, most reliable ones.

Max Roser: Yes, that’s a concern. And I think we often decide against working on a project because we don’t have good data to report on. But it’s also the case that there are arguments that push you in the opposite direction. For example, on mental health, all of the research that we have suggests that mental health disorders are just very common in countries around the world. And we want people to take mental health much more seriously as a global health issue. Now, the data that is available on a global scale is of poor quality. And so you’re caught up in this dilemma where, on the one hand, the data is poor and you would rather not publish it. On the other hand, by not making the data available, and presenting no information about it, you leave this massive global health problem without any reporting. And in this case, we decided that the data should be made available and should be discussed. And we’re working now with Saloni, who just joined us in the team, to get a better understanding of global mental health issues.

How to be more like OWID

Max Roser: Our key role and why our work is more interesting is that we have this cross-country international perspective, right? That’s of course something that a particular country wouldn’t do, and so there’s no fault there. On the other hand, it’s an issue also just of software. The tools that are readily available just aren’t that great. The fact that much of our team is actually busy building visualization tools shows that, right? One of the hardest things in getting Our World in Data off the ground was to find funding for that work, because foundations, anyone that gives out grants, wouldn’t quite understand that. They were like, “You want to build visualization tools? Why don’t you just use Excel?”

Max Roser: Or if they’re a bit fancier, like, “Why don’t you use Tableau?” And so the tools don’t exist as easily. If someone is looking for tools, I would give a shout out to Datawrapper. That’s a really nice software solution for publishing data on the web. And we are also trying to do this ourselves. Our advantage is that you can extract data out of a large database and visualize it, and all of our work is open source. And it’s also part of our mission to make those visualization tools more used in government agencies, international organizations.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It’s an interesting phenomenon. I’ve heard from quite a few people that it’s very hard to get resources to build platforms and tools that then other people are going to use to put to a lot of purposes. And I wonder whether it’s just that it’s harder to demonstrate at that stage what the concrete output is going to be, and what the value is going to be. It’s sufficiently far away from the final delivery point that it’s hard to prove to a grantmaker that it’s worthwhile.

Max Roser: Yes. And also there is not really a delivery point. I think that’s also a key aspect. You want to build these kinds of tools to be usable over a long period of time, and that’s where many of these tools fall short. There are often great efforts that are one-offs, right? There’s new money at this international organization, now they’ve built this amazing presentation of their data. But two years later, the web has moved on. There are new tools. The databases have changed, and it’s this half-broken tool. And so the key in our work is to keep maintaining this infrastructure and keep developing over a long period of time. And I think that would be something that would help international organizations if they see the presentation tools as part of their core work, that they actually have to have an in-house team that keeps on working with them, and that they don’t outsource it to an agency that does a one-off job that’s good for the big launch, but is broken a year later.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Our World in Data work and pages

- Country exemplar Project

- COVID Data Explorer

- COVID country profiles (UK)

- COVID-19 deaths and cases: how do sources compare?

- We teamed up with Kurzgesagt to make a video about the COVID-19 pandemic

- Vaccination data set

- What is Economic Growth?

- Jobs

- Donate

COVID-19

- Johns Hopkins dashboard

- European CDC

- COVID Tracking Project

- COVAX

- Professor Neil Ferguson on the current 2019-nCoV coronavirus outbreak

Data

- Gapminder

- World Development Report

- Carbon Brief

- Nature Scientific Data

- World Bank database

- OECD statistical database

People

- Dr. Moritz Kraemer

- Marc Lipsitch

- Peter Brecke

- Tim Harford

- Tom Chivers

- Bryan Caplan

- Hans Rosling

- Rest of the team

Books

- Poor Numbers: How We Are Misled by African Development Statistics and What to Do about It by Morten Jerven

- The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

Other links

Transcript

Table of Contents

- 1 Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

- 2 The interview begins [00:01:41]

- 3 Our World In Data [00:04:46]

- 4 How OWID became a leader on COVID-19 information [00:11:45]

- 5 COVID-19 gaps that OWID filled [00:27:45]

- 6 Incentives that make it so hard to get good data [00:31:20]

- 7 OWID funding [00:39:53]

- 8 What it was like to be so successful [00:42:11]

- 9 Vaccination data set [00:45:43]

- 10 Improving the vaccine rollout [00:52:44]

- 11 Who did well [00:58:08]

- 12 Global sanity [01:00:57]

- 13 How high-impact is this work? [01:04:43]

- 14 Does this work get you anywhere in the academic system? [01:12:48]

- 15 Other projects Max admires in this space [01:20:05]

- 16 Data reliability and availability [01:30:49]

- 17 Bringing together knowledge and presentation [01:39:26]

- 18 History of war [01:49:17]

- 19 Careers at OWID [02:01:15]

- 20 How OWID prioritise topics [02:12:30]

- 21 Rob’s outro [02:21:02]

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Hi listeners, this is the 80,000 Hours Podcast, where we have unusually in-depth conversations about the world’s most pressing problems, what you can do to solve them, and what the criminal sentence should be for publishing good research as a PDF alone.

I’m Rob Wiblin, Head of Research at 80,000 Hours.

Today’s guest, Max Roser, is the person who got the website OurWorldinData.org off the ground. Most of you will already have heard of Our World in Data, but for those who haven’t, today’s your lucky day, because you’ll get to check it out for the first time.

Our World in Data has been in wide use for a few years now, but it really exploded into the public consciousness in April and May 2020 when it had the best collection and presentation of the COVID-19 numbers and graphs that people were desperate to access. People like me were checking it many times a day to stay up to date on what was going on.

When politicians or health experts got up in front of their nations to explain how the crisis was progressing and what had to be done, as often as not they were standing in front of familiar graphs produced by Our World in Data.

The website is so obviously necessary, and — given that it’s been such a success that is used by millions of people around the world every day — I was surprised to learn just how tenuous its survival was. Early on, Max, true to his reputation as a lovely and thoughtful guy, continued developing Our World in Data with almost no funding and almost no reward, just because he thought it was important.

We talk about a lot in this episode. In particular I wanted to know how a nonprofit with a handful of staff was able to outdo major institutions and newspapers that have thousands of staff, and become the go-to place to understand the COVID epidemic — especially when it came to testing and vaccination rates.

I hope you enjoy that story, and some of the many other lessons Max has learned building Our World in Data over the last ten years.

Alright, without further ado, here’s Max Roser.

The interview begins [00:01:41]

Rob Wiblin: Today, I’m speaking with Max Roser. Max is an economist at Oxford University who focuses on understanding large global problems such as poverty, disease, hunger, and damage to the environment. Max is most famous as the founder and editor of Our World in Data, a scientific online publication that has the goal of presenting research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems. In recent years, it has grown from a fairly small operation to a website with more than 10 million monthly users. And it’s used by more media outlets than it would be possible to count here. In 2020, it exploded onto the scene as the best place to get all the data you might need in order to understand the COVID-19 pandemic. Its resources were referred to at the highest level by global leaders, and also read by me every single day of the pandemic. It also presents data and analysis of all the world’s key measures of success and failure, like pollution levels, changes in education levels, and deaths from natural disasters. Most importantly of course, Max is also a regular listener of the 80,000 Hours Podcast. Thanks for coming on the show, Max.

Max Roser: Thank you very much for the invitation, Rob.

Rob Wiblin: I hope to chat about how you grew Our World in Data in the crazy days of early 2020, and the most important things that you’ve learned while building this resource. But first, what are you working on at the moment, and why do you think it’s important?

Max Roser: Well, I’m always working on Our World in Data, so the answer is kind of easy. And currently I’m splitting my time basically between mornings and afternoons, as I often do. In the mornings I’m currently writing a series that I’m calling something like ‘The world’s big problems in brief.’ And the idea is that for much of my recent writing, I was writing fairly long articles, and I would like to condense them and give the key takeaways in a briefer format. And then the afternoons are spent discussing the COVID data, and maintaining our database there, building the visualization tools that are necessary, and doing all the admin and finance work that comes with it.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I think that a compilation of the key takeaways on each of the different topic pages that you have on the website could be incredibly popular. Or at least it would be incredibly popular with me. I don’t know, maybe I overestimate how many people share exactly my interest. Well, I mean, the fact that you’re getting 10 million people on the website every month suggests that there is a hunger for people to actually get in touch with reality, and see what the basic facts are about the world.

Max Roser: Yeah, that’s right. There’s just much more interest than I would have expected. And I think it makes sense to try to condense it a bit, because for those who know our current work, it’s often pretty lengthy, and it’s very hard to read from top to bottom. The researchers always want to put in all of the caveats and all of the references. And I try to work a bit against my own instinct there and try to get it done a bit more succinctly.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, it is incredibly important to make it short enough that a reasonable number of people who actually have jobs and families and stuff can have a chance to absorb it. I think that’s a criticism that has been made of the 80,000 Hours website as well. It is a very tricky balance. You want to kind of sum it up quickly so that people can actually absorb it and remember it, but on the other hand, often these caveats can be incredibly important, and potentially you can end up accidentally spreading misinformation if you try to simplify stuff too much. So yeah, not an easy balance.

Our World In Data [00:04:46]

Rob Wiblin: What is your big-picture theory for how Our World in Data is going to improve the world?

Max Roser: The mission that we have is to present the research and data on the world’s largest problems so that we can find ways to make progress against those problems. That’s what we want to achieve. And then the way that we hope to achieve this is basically twofold: On the one hand, there are already lots of people who have this idea, that work on a big global problem, whether it’s a health issue, or a disease, or whether it’s getting kids into school and improving education. And for all of those people, we just want to serve the information in an accessible and understandable format. That’s really the key of that.

Max Roser: And then we also have this second part of the mission, where we would like to expand that community. Where I think lots of people are just very concerned about large global problems, but are very far away from the research and from the data. And so they have only a poor understanding of what the problems really are, how they compare in size, whether we are making progress or not, etc. And so we have this idea that many people are concerned, but don’t actually know that it’s possible to do something about these problems, and that there are ways forward. And so we try to encourage them and motivate them to see that it’s worth dedicating time, effort, even a career, possibly, to support this kind of work.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Obviously a lot of the positive impact that you have is going to be very diffuse in just allowing a very large number of people to have a more accurate model of the world, and set better priorities in their life or what they write about. But do you know of any kind of concrete, important, positive impacts that you’ve had where maybe someone, a bureaucrat in government, or a minister, has come to you and said, “Because of the data that you compiled and the fact that we could interpret it quickly, we got this better policy outcome.”

Max Roser: Sure, I think it’s right what you said at the beginning. Much of what we do is actually building infrastructure. That’s how we increasingly see our role. On the one hand it’s these big datasets that we make available to institutions, to big media outlets, and then you see it in print around the world. But sometimes it’s obviously the very concrete impact that’s most motivating and also most surprising.

Max Roser: One that we found very exciting is that we’ve heard from psychologists and psychiatrists in the last few years who actually use our work with their patients. So they have patients that suffer from anxiety, from depression, and that often feel in a way overwhelmed just by the amount of problems in the world, and just have this bleak outlook that nothing can be done. And yeah, it turned out that several psychologists rely on our work to show this to the patients. And show that yes, these problems are large, but it is also possible to do something about it.

Max Roser: And we all found this, at the beginning, very surprising. Because often the rebuttal to our work is, “It’s all this data, it’s all this abstract information. It doesn’t really touch people’s hearts in any way. It doesn’t move anyone.” And then to hear from the experts on what actually touches people’s minds and hearts that they are using our work in this way, yeah, we found it very surprising and encouraging.

Rob Wiblin: That’s fantastic. I never would have guessed that you were going to give that answer. I almost hesitate to ask this question, because the answer might be somewhat embarrassing for more traditional publication methods, but how many more views do you think your research is getting because it’s on this Our World in Data website that’s nicely designed and all comes together as a cohesive package, rather than say, in a published paper?

Max Roser: It’s hard to estimate, because obviously the information is a bit different. Like we are often very far away from the research frontier. And research at the frontier is obviously read by a different audience. So it’s a bit hard to make a one-to-one comparison. One data point that might be a bit relevant is the World Bank has this flagship report called the World Development Report. And I know that last year’s World Development Report was downloaded 400,000 times. Our monthly users are 25 times higher than that.

Rob Wiblin: Is it similar data? Is there anything that you could perhaps put that down to, is it maybe the presentation, or like how clearly and straightforwardly the information is communicated?

Max Roser: There’s lots to discuss there. One key thing I think is that many of these reports are published in PDFs, and it’s just very hard for people to access PDFs, to read PDFs. They don’t show up in search as easily. There’s no navigation in a PDF. So I think it’s just a really big flaw in the way that research is published, that we go for this paper substitute online. Like it’s hard to read on a mobile phone, as everyone knows. And so just by… Like one very simple thing is that it’s an HTML page rather than a very unhelpful format. And I think overall, search is just hugely important for our reach. I think sometimes people have a bit of a wrong idea there that social media plays a big role, but it’s all search. And that’s not something that’s on the mind of many researchers in their public outreach efforts, that they have to care about SEO. But it’s the most important.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. SEO is search engine optimization. That’s something we actually noticed during our annual review last year, was that we’d been underestimating how important the organic search traffic was. People who follow me on Twitter will know that it’s kind of a passion of mine, giving people a hard time when they have an amazing report, and an amazing bunch of research or information, and they only publish it as a PDF and have no HTML version, because it’s just so destructive to the amount of traffic and the number of readers that you can get.

Rob Wiblin: Like in addition to the problems that you were mentioning, you also can’t save it to things like Instapaper or Pocket. And you can’t find any way to have them read to you. You can’t share them on social media. Even if social media isn’t the most important, PDFs do not have share attachments with an image and a title on Twitter or Facebook. So yeah it’s just… Listeners, please, if you are publishing research that you think is valuable for people to read, please do not only publish it as a PDF. It just makes no sense.

Max Roser: Yeah. It’s a bit odd how little this is discussed in academia and institutions. Like PDF is so often the default, and it’s just not helpful. You can’t update it, you can’t navigate from it. You’re outside of the navigation of that page that you’re part of, so it’s hard for a user to transfer somewhere else and explore some other corners of your work. And in our work, of course, it makes a big difference. Because the website allows us to do these interactive visualizations that you can’t have in the PDF. And very long term, our idea is also to build a content management system that replaces that way of publishing research. Where, as new data becomes available, the research paper incorporates that data, reruns the models, redraws the charts, and keeps the research up to date.

Rob Wiblin: I’m so glad that I finally got a chance to rant about that gripe on the show.

How OWID became a leader on COVID-19 information [00:11:45]

Rob Wiblin: Alright, let’s push on to a story that I haven’t heard, and I think maybe the Our World in Data team hasn’t yet talked about, which is how you ended up becoming maybe the number one go-to resource for COVID-19 information. At least, I think, in English.

Rob Wiblin: I was very closely tracking the COVID-19 pandemic from February 2020 onwards, and it’s a little bit hard to remember now — you have to kind of cast your mind back to the experience that we were actually living through at that time — but I was trying to figure out in which countries COVID was taking off, which countries were managing to contain it better, in order to try to line up which policies might be working better than others. But every time I wanted to go to a case study and try to make sense of what was happening in that country, it was like going on a unique archeological dig to try to grab the data from a bunch of different sources, probably some horrible government website. And then I had to find out whether the data collection methods were completely inconsistent with other countries, that would then make them incomparable… I would have to then get the .csv file, put it into a Google spreadsheet, and then build my own like extrapolation model to see where things were going. And then I might realize that the data was so poorly collected that it didn’t really show anything at all.

Rob Wiblin: One of the astonishing things for so long was that countries were reporting the number of confirmed cases that they had, but they weren’t reporting the number of tests they were conducting or what the positivity rate was. So obviously countries that were organized enough to have a lot of tests being conducted, it made them look like they had far higher rates of COVID, versus a country that simply wasn’t conducting any tests at all, where it seemed like the pandemic wasn’t present. The fact that you couldn’t get good testing data made these inter-country comparisons extremely difficult and very laborious in each case.

Rob Wiblin: Anyway, yeah, so Our World in Data I think changed that over the course of March and April and May. And it became possible, using the tools that you developed, to actually quickly get a grasp of what is going on in all of these different countries with cases, and testing, and deaths, and now vaccinations.

Rob Wiblin: And I imagine it was a massive… It was a huge assistance to me in understanding what was going on, and what policies were working. And I can only imagine it was the same for bureaucrats, who might only have 20 minutes in a day between putting out fires everywhere else to actually try to understand where things might be working. With that little rant out of the way, I’m curious to know what is the story by which, what was really a much smaller organization than say the World Health Organization, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or these other big agencies… How did you manage to become the go-to place for people to learn about the pandemic? How does the story start?

Max Roser: Yeah, it was really a very different time, and we were also a smaller team. We grew quite a bit in the last year. So at the beginning of last year, there were about six people on the team. Two developers and four people that worked on research and data, and all of the administration that comes with it. And it started fairly early. I have a good friend here at the University Dr. Moritz Kraemer, who is a researcher in infectious diseases. And he was starting to work on it very early in January. So he basically first told me about it.

Max Roser: Then I went to Africa, and for several weeks I was in Tanzania and South Africa. And so, it was a bit further away from me. I was working there, and I think that delayed us a little bit, unfortunately. But when I came back from there, we knew that it was a big global problem. So it would fit the Our World in Data focus of making research and data on global problems available. But we were still somewhat hesitant. And maybe I should also say, my understanding of COVID in these early days was also hugely influenced by you guys at 80,000 Hours. I was always following your projections. Like you had this very simple model where you just looked at this exponential growth rate, and like three days later it was still kind of fitting the data. And eight days later, it was still fitting the data. And I thought this very straightforward crude approach was really helpful. So thanks for that.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Initially I was like, “Well, it’s probably going to grow something like an exponential.” And I just got the numbers and was like, “It kind of fits an exponential.” And then I forecast forward for all of these countries, including the country that I was in, and the U.S., and was like, “Wow, what if it continues to follow the same exponential?” I got all of these responses from people who knew an awful lot more and had studied all of these fancy things saying, “No, an exponential is wrong. You should be doing this other way.” And as it turns out, exponential was the data that came up extremely well. Sometimes the simple fit can be the best.

Max Roser: Yeah. I thought it was really helpful. And I thought this first principle way of looking at it, rather than letting maybe too much knowledge of the infectious disease modeling get in the way, was a helpful way of looking at it. And also, obviously, some infectious disease experts were influencing me at the time. I remember looking at Marc Lipsitch’s account at the time. And I think he was saying up to 70% of the world’s population will at some point be infected by the virus? And my first reaction was like, “This can’t possibly be.” But I didn’t have a good idea of why it shouldn’t become the case.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I can’t remember who’s the head of the Imperial Research Group in London, but he said basically the same thing, that I think at least half of the world would get this virus. And he said that in like the first week of February in a YouTube video that went really viral. So yeah, there were definitely some people who were on the ball.

Max Roser: Yeah, exactly. And that really helped. But we were still hesitant in mid-February. And one reason why we were hesitant was that we were tiny, and funding was obviously a headache, and we had other issues to work on. Another one was that we didn’t have anyone in the team who was working on infectious diseases. And that was in a way very unfortunate, because we actually had a colleague the year before who is an infectious disease expert. But she left us basically just as the first cases were reported. That was really unfortunate.

Max Roser: And then the other aspect was that in all of our work, we always try to put most effort into those problems where others don’t. So maybe if the current work we’re working more on is biodiversity and deforestation than say on climate change, it’s not because we don’t think that climate change is as important, but because there’s lots of good information on climate change from other institutions. And so we were also thinking, well, there’s The Guardian and The Financial Times and The Economist, and all of them are already on the COVID reporting.

Max Roser: But then I think the thing that changed it for me was really just how difficult it was to access the data. And the other aspect was that I thought the media was not telling the story that was most important at the time. It was very much focusing on low case numbers. It was like, “Here in Brighton, there are three cases reported. And over in Cardiff, there’s another case, and that’s it.” But the real story was the growth rate. And that was really the key thing that you have to know in an outbreak of an infectious disease, and the focus wasn’t on the growth rate. And I was going mad. I just couldn’t believe how poor this reporting was.

Max Roser: And then we started bringing the data together, and as you said, it was ridiculous how difficult it was to bring this data together. It was… At some point we started working very seriously on it, and Hannah Ritchie, my colleague, and the team and I were having these morning phone calls every morning, super early. She always wakes up at like 4:00 AM or something. We had these early calls where we would be looking at the PDF, like the WHO was actually publishing their data in a PDF, it wasn’t even a spreadsheet. And we would go through, and Hannah would be dictating, like, “Philippines: 7. Indonesia: 9. Thailand: 14.” And I would be typing the numbers down in a spreadsheet. And it was obvious that the numbers wouldn’t add up. It was like, yeah, the total in Thailand is now lower than the total in Thailand was yesterday. And the total in the world is lower than the numbers in China alone. And it was just clear what a poor state the data was in.

Rob Wiblin: Just to be clear, you’re saying… I suppose at this stage you were maybe just trying to understand what was going on for your own purposes, not even for Our World in Data. And like me, and like lots of other people, you’re going to these authorities, like the World Health Organization, and saying well, what are the numbers actually showing? I want to explore this myself. And then once you start looking at them and comparing the numbers they’re giving, even within the World Health Organization’s own reports, they’re like direct contradictions. Is that right?

Max Roser: Yeah, that’s right. We wrote about it at the time, yeah. The numbers didn’t add up. It wasn’t like huge mistakes, but there were a couple of mistakes every day where you knew that it couldn’t be accurate. And it was just very painful for anyone to use this information. And so we were just compiling these spreadsheets. And another reason why we couldn’t move as fast as I would have wanted was that in all of our work, always, the shortest frequency for data is the year.

Max Roser: We had year by year information, decade information, information by centuries, but we never had any information from day to day. And it’s one of these things where you set up your database structure in a way, and then you’re kind of locked in. And so it was actually not easy for us to switch to daily reporting. All of the tools that we’ve built didn’t allow that. And then one of the developers who came into the team just fixed it incredibly fast. Like we couldn’t believe how quickly he wrapped his head around our architecture. And the next day we were able to plot charts over days.

Rob Wiblin: Who was that?

Max Roser: His name is Breck Yunits. And it just happened that we were hiring at the beginning of the year, in late 2019, and these new colleagues, they just joined us in May, February, and March. And so they entered Our World in Data in this incredibly hectic period. I guess they—

Rob Wiblin: …weren’t sleeping very much.

Max Roser: —they must’ve been pretty shocked by the first weeks of their work experience.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So what date are we up to now?

Max Roser: So then when we were that far, that was probably like late February.

Rob Wiblin: So you were actually kind of ahead of the curve, because the media was kind of playing it down. There were relatively few people in the last week of February, I remember, who were really worried. The official line was that we shouldn’t worry too much.

Max Roser: Yeah, that’s true. I wish we would have been earlier. But it’s true that some big media organizations weren’t quite up to speed with what was happening. And I remember it was also just like a hectic time for us on a personal level, right? On the one hand we were working all the time. But on the other hand, I had to call my parents, call my sisters, friends, and tell them… And I wasn’t as public, obviously, about it at the time, I mean, I’m not an infectious health expert, so I thought my role is getting the data right. Making it possible to plot the data on a chart, and that’s it. But personally I was thinking it’s much more serious than most people think. And so I was also busy much of my time just getting on the phone with friends and family and telling them they should take this more seriously than maybe the media was suggesting at the time.

Rob Wiblin: Right, okay. So we’re in late February, you’ve kind of redesigned parts of the website so it can potentially offer this COVID-19 data in a timely way. That makes sense. Now the team has some familiarity with the data sources, and they’re copying them out verbally into spreadsheets, because they’re not being offered that way.

Rob Wiblin: When did things kick up a gear? Because there was a point at which it seemed like you guys went all in on this.

Max Roser: Yeah. There was some preparation work where it wasn’t actually online yet. But once we then put it properly online, it went pretty fast. I would have to look at the analytics to see exactly how this went, but that was then probably the beginning of March where we were compiling the research that was there at the time. Mostly out of China. Our basic job at the time was cataloging confirmed cases and confirmed deaths, always with the emphasis that it’s confirmed cases, and that this is an undercount of total cases. And then there were two efforts on top of that: One was to get the testing data. We started at some point early in that month with that. And I thought that was just also poor reporting from much of the media where it was actually reported as cases. It was always like, “How many cases are in your neighborhood? How many cases are there in different countries?” But it was—

Rob Wiblin: …1/100th of the true number.

Max Roser: —what cases are known. Right. Exactly. It was a huge undercount, obviously. And so we wanted to get the testing data together. And then a couple of colleagues, Joe Hasell, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina started compiling these testing figures showing also just how big the differences are, where South Korea was ramping up testing very rapidly, Germany to some extent, and the U.K., for example, where we are based, did much less so, and just explaining how important it is to know the number of tests that are done.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. That makes sense. I’m guessing that there were a couple of barriers to you all thinking that it’s your responsibility to take this on. One is we’re not experts in contagious disease. So why would we be doing this? We in general don’t do things on a day-to-day basis. We’re reporting long-term trends. That’s kind of our thing. And on top of that, you don’t have the resourcing of these enormous agencies whose statutory authority is meant to be to do this kind of thing. But I’m guessing that over the course of March, you just realized that no one was picking up the mantle on this, that there wasn’t really a better source. I guess there was the Johns Hopkins dashboard.

Max Roser: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Rob Wiblin: But did you gradually come to realize that if you didn’t do it, it might not really be done properly?

Max Roser: I think it took me a lot longer. I think it’s also important to note that there were some institutions that did really well, like the European CDC, based in Sweden. We switched from the WHO data to the European CDC data on confirmed cases and confirmed tests, and those guys were really on it. They were awesome. We were getting in touch with them early on. They were helpful in the calls, and they were just really focused on getting the data right. I know that those guys over there, they woke up every morning at 4:00 AM and were compiling the data from countries around the world. What’s maybe also not so obvious for listeners that aren’t getting their hands into country-by-country statistics, and that rely mostly on aggregate sources, is just how messy this transfer from the data from the country to an aggregate data source is.

Max Roser: It’s not like there’s some official channel where someone reports the data in a clean spreadsheet in the morning, and the receiving agency puts it all in a clean spreadsheet from there. Sometimes it’s like that, but it’s very rarely the case. And in most cases it’s super messy. It’s like some country publishes their data in a .csv file on the health ministry. That’s cool. Sometimes it’s really obscure ways, like the health ministry has a Facebook account, and on that Facebook account, they share a screenshot of some table. And in that table, that’s the only place where they report their latest data. That was the case from the start, and it’s still the case today. And so the guys at the European CDC did that job every morning. They had a huge catalog of obscure sources where they went from page to page in the morning and typed up the numbers from countries around the world.

Rob Wiblin: And it’s so easy to mess that kind of thing up, because you’ve got this ambiguity about which… Well, there’s multiple different problems. One is ambiguity about which day the data falls into, and you can easily put it in the wrong one, or double count it, or not count it. Another one is what do you do with data revisions? Do you then go back and change the old ones? Because then people are going to be like, “The numbers don’t add up.” This mere data entry thing is somewhat trickier than it sounds. But yeah, I really do want to give a shout out to the European CDC people. I think all of my data import instructions in my Google spreadsheets were pointing towards their .csv exports. Their data seemed more reliable and more consistent than anyone else’s. So it sounds like that was a huge number of person hours that went into that, and a huge amount of attention to detail and getting up at 4:00 AM, so… Respect.

Max Roser: Yes. And I think just also very dedicated people that took their job very seriously, and they did this one job thoroughly.

COVID-19 gaps that OWID filled [00:27:45]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. So I guess the European CDC was doing this good job within this particular remit, but what did you think was lacking that Our World in Data could potentially add to this by focusing on COVID-19?

Max Roser: It’s shifted a bit. Back in March, there were really several strengths to the work that we were doing on COVID. One was explaining the key metrics and helping readers to make sense of what the case fatality, the infection fatality rates are, how these two measures differ, how they might change over the course of an outbreak, how the amount of testing is impacting these metrics. And that was helpful for a lot of journalists at the time. We were in touch with many journalists, and then we did less and less of that because the journalism around COVID just hugely improved over time. It wasn’t great back in February, March last year, but it’s pretty awesome right now. There are lots of really great people.

Max Roser: Then another strand of the work was to compile these aggregate datasets on international statistics. We took the confirmed cases and confirmed deaths from the European CDC, but we then later compiled many more sources. We did the testing database, that was in our hands. We did aggregate the data on excess mortality. We compiled survey information from people’s opinions, and then much more recently, obviously, the vaccination data. And the key job there was, on the one hand, to produce a clean spreadsheet that other people could then rely on, that they could pull into their reporting — so big news organizations could just pull our .csv file every morning and then update all of their statistics on their outlets. And the other one was to build the tools that make it possible to explore the data right there on our site, because that’s something I think even the ECDC was struggling with. They made the data available, but the tools to then actually visualize the data and compare countries and understand the data, that wasn’t great. And it’s also not their job in a way. Right? So I think that’s fair.

Rob Wiblin: At some point I recall you started adding these country profiles where I think you would have a single page that was explaining the state of play in a particular country, like say Taiwan, where you would go through all of the key facts and figures. And then you would also add some interpretation about, is Taiwan doing a good job, and what stuff that they’re doing might be actually important. And I guess these were partly there in order to perhaps inform policymakers who were scrambling to figure out what to do.

Max Roser: Yeah, that’s right. We did this project called the Exemplar Project, and we collaborated with health experts in those countries, but that started in March. So in March it was my job to figure out which countries actually did well. Actually the two of us were in touch about that at the time, I remember.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. We were, yeah. I think you ended up making an awful lot more progress on it than I did, but I was curious about this topic.

Max Roser: Right. I was selecting the countries that did well. And at the time we selected Vietnam, South Korea, and Germany to have a bit of a geographical mix and also a mix of different income levels of the countries. And at least for the first wave, that was actually a good choice. Germany did obviously much worse last winter. And then we handed it over to country experts. There were colleagues involved from Korea, colleagues from Harvard, and they tried to really understand how those countries reacted. What did they get right? What were their policies? And we then later published it on Our World in Data.

Incentives that make it so hard to get good data [00:31:20]

Rob Wiblin: It seems like there’s maybe three different niches that you fell into. One was this data-sourcing, data-cleaning and organizing process, especially across different states and across different countries. Then there’s presenting the data clearly, which for some reason it seems like government agencies, it’s not their specialty to present data in a way that makes sense to just a typical person off the street. And then maybe the third one is analyzing that and offering opinions about what’s good, which I mean many people were doing, but again, sometimes government agencies feel somewhat constrained in what they can say publicly because they do have an awful lot of stakeholders.

Rob Wiblin: It’s kind of a bit of a running joke that national agencies and international agencies are just so bad at providing data in a way that is useful to researchers and useful for doing analysis, that this kind of thing where, yeah, it’s released on a PDF with a screenshot and then you have to copy it out manually, that is like… Not everything is like that. Some countries and some agencies do a fantastic job and deserve credit. But it’s far more common than it ought to be. What is it about the nature of the organizations or the incentives that they face that means data that people desperately need is often so hard to access and compile?

Max Roser: Yeah. I think what’s lacking somehow is this understanding that the output of data at one institution is the input of data at another institution. Many institutions seem to think their job is done once the data is out in some shape or form. And they’re not really thinking that someone else is picking it up from them. It is hard to understand why this is happening, and I don’t quite know the answer. I mean, it’s definitely not a problem that is on many people’s minds. It’s not a problem that the public is very concerned about, even though it very much impacts public knowledge in the end. And so it’s just pretty absurd.

Max Roser: Even in March last year, I remember there was one other effort that was compiling testing data at the time. And those guys, for this issue that I was mentioning that sometimes it’s on a screenshot on a Facebook account, those guys were building machine learning tools to automatically read the data off a Facebook image. It’s absurd, right? We have this amazing technology that can automatically extract information out of an image, but then it’s used in this completely bonkers way where the data was in a spreadsheet before.

Rob Wiblin: We’re having to apply this absolutely world-class technology in order to undo the most basic errors some people are making. Yeah. That’s humanity in a nutshell, to some extent.

Max Roser: Yes.

Rob Wiblin: I mean, there’s probably a whole bunch of different factors. It seems like government bureaucracies often have lots of rules about how they operate, and they don’t necessarily allow individual staff members to decide that they’re going to do things a different way. And often there’s good reasons for that, because if you give people lots of discretion, then they can potentially do a much worse job as well as a much better job. I guess also they don’t often have a phone number on the website where you can just call up the person who’s posting this on Facebook and say, “Have you considered putting this in a spreadsheet? Just make a Google spreadsheet and copy it in there, and then we can extract it.”

Rob Wiblin: It’s sometimes a little bit hard to communicate with these organizations, especially during a catastrophe where everyone is run off their feet. It’s also kind of a cliche that agencies like this are not very good, even when they have the data and they’re kind of presenting it, they don’t tend to present it in the beautiful graph format that Our World in Data has. Do you have any idea why that might be, and what people can do inside these agencies if they look at Our World in Data and say, “I wish our website could be like that?”

Max Roser: Our key role and why our work is more interesting is that we have this cross-country international perspective, right? That’s of course something that a particular country wouldn’t do, and so there’s no fault there. On the other hand, it’s an issue also just of software. The tools that are readily available just aren’t that great. The fact that much of our team is actually busy building visualization tools shows that, right? One of the hardest things in getting Our World in Data off the ground was to find funding for that work, because foundations, anyone that gives out grants, wouldn’t quite understand that. They were like, “You want to build visualization tools? Why don’t you just use Excel?”

Max Roser: Or if they’re a bit fancier, like, “Why don’t you use Tableau?” And so the tools don’t exist as easily. If someone is looking for tools, I would give a shout out to Datawrapper. That’s a really nice software solution for publishing data on the web. And we are also trying to do this ourselves. Our advantage is that you can extract data out of a large database and visualize it, and all of our work is open source. And it’s also part of our mission to make those visualization tools more used in government agencies, international organizations.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It’s an interesting phenomenon. I’ve heard from quite a few people that it’s very hard to get resources to build platforms and tools that then other people are going to use to put to a lot of purposes. And I wonder whether it’s just that it’s harder to demonstrate at that stage what the concrete output is going to be, and what the value is going to be. It’s sufficiently far away from the final delivery point that it’s hard to prove to a grantmaker that it’s worthwhile.

Max Roser: Yes. And also there is not really a delivery point. I think that’s also a key aspect. You want to build these kinds of tools to be usable over a long period of time, and that’s where many of these tools fall short. There are often great efforts that are one-offs, right? There’s new money at this international organization, now they’ve built this amazing presentation of their data. But two years later, the web has moved on. There are new tools. The databases have changed, and it’s this half-broken tool. And so the key in our work is to keep maintaining this infrastructure and keep developing over a long period of time. And I think that would be something that would help international organizations if they see the presentation tools as part of their core work, that they actually have to have an in-house team that keeps on working with them, and that they don’t outsource it to an agency that does a one-off job that’s good for the big launch, but is broken a year later.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I just want to tell a story of another project that has some similarities with what Our World in Data did with COVID-19, finding a niche where something that should have been happening wasn’t happening and then filling it, even though it wasn’t really their place to do it: the COVID Tracker group in the United States. So you might think that the United States is a rich country with quite a developed government, so there would be someone whose job it was to compile all of the data on positive tests in different states, in different hospitals, and so on, in order to figure out how many positive COVID cases there were each day in the United States.

Rob Wiblin: But it turned out that nobody was doing this. And then I think a bunch of journalists from The Atlantic and I think some other newspapers basically just realized after a while that it wasn’t that this was about to be released suddenly, that some agency was about to start collecting and releasing this dataset. They realized that it was seemingly nobody’s job, or at least the people whose job it normally was weren’t going to do it. And so they created the COVID Tracking Project, where this bunch of freelance journalists basically just took it upon themselves to call around states and hospitals and scrape data off of all of these websites every day for something like a year in order to be the resource that people would go to to know how many COVID cases there were in the United States. And I think it was an amazing effort, heroic effort, and it’s fantastic that they were able to fill that gap as quickly as they did. But I suppose it does raise a systemic question of how can it come to this? How can it come to this even in a country as rich as the United States?

Max Roser: And this wasn’t only in the U.S. The COVID Tracking Project I think was a huge success and it’s great that they stepped in, but in many countries there were similar issues where the data was only reported in some regions and no one was aggregating these figures. And it was often these volunteer groups that would actually produce the most useful datasets. And it’s of course also not just COVID, right? On all of these many global problems, the efforts that go into the data production are in no relation to the efforts in analyzing this data later. There’s so much fancy research with fancy statistical models being done on the basis of very poor data. And I think the balance between funding for good data and funding into research isn’t quite right. We should put more resources into getting the data right first.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It seems probable that in future disasters we’re also going to have to rely on people to just fill gaps that they notice that no one else is filling.

OWID funding [00:39:53]

Rob Wiblin: Something that can make it hard for organizations to suddenly jump in and fill these roles is having the necessary funding immediately on hand in order to scale up, and also to put towards a specific cause. Because sometimes nonprofits have grants and they might have money in the bank, but it’s all dedicated to specific projects and they can’t then spend it on something else when circumstances change. How did Our World in Data either end up having enough money to throw at this problem really quickly, or I guess maybe raise the money really quickly?

Max Roser: Yeah. There’s two things to it. One is that we always try to not get restricted funding because of this. It’s a very common thing that the donor wants to restrict funding for a particular purpose that they think is most important. But I think it’s rarely the case that a donor knows better than the actual organization of what to do. And so luckily we always fought for unrestricted funding. And the other one was reader donations. A good chunk of our funding comes from reader donations, and that is completely unrestricted. That’s people who give us anything between $20 and a couple of thousand dollars, and we have this in the bank as flexible funding that we were able to use in April, May, also to grow the team, to pay new colleagues, to get on board where we didn’t have to deal with any funders. So that was really, really helpful.

Rob Wiblin: Speaking of hiring, it seems like it would be hard, in such a frantic time when you’re trying to build these tools and fill this gap, to also then be making good decisions about hiring. You have to test people, see if they’re a good fit, train them up. How did you balance the need to rapidly expand the team with the need to just keep up with the day-to-day flood of work?

Max Roser: To a good extent it was luck. We had hired some colleagues before the pandemic started, and they were coming on board in the early days. It was also luck that we got in touch with some colleagues during the pandemic that turned out just to be great, like Edouard Mathieu, who is maintaining the vaccination dataset now. He’s the single guy who built the vaccination dataset really. He joined us last March, in addition to his full-time job. It was mad. He was working two full-time jobs. So every day at 4:00 PM, he would start his second full-time job with us to build the data. And he just turned out to be super good at his job. And I didn’t know that. I guess he didn’t know that. It was just a bit of a lucky coincidence.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Cometh the moment, cometh the person.

What it was like to be so successful [00:42:11]

Rob Wiblin: When you started to have success and had huge traffic numbers to the website, I’m guessing probably at some point you had to update your servers in order to keep them operating. How much of a rush was it for you and for the team to realize what an impact you were having?

Max Roser: It was maybe less of a change than your question suggests. We also had periods of high traffic before. In the very early days when I started by myself, any particular user was as huge. I always had two screens, and Google Analytics was running on one screen. And when someone somewhere was visiting Our World in Data, I would just stop everything and watch. There’s actually a person from the U.S. looking at the sites! I think the thing that tests you is Reddit, because if you get traffic from Reddit, it’s just so much. And in the early days, it often broke the site. Even the second developer that was working with me was getting everything up for these ‘Reddit hugs of death,’ that’s why they’re called, right?

Rob Wiblin: For listeners who don’t know, that’s when you suddenly get hundreds or thousands or millions of visitors from Reddit, which then brings your site down because the server can’t keep up.

Max Roser: Exactly, so the hugs of death, they prepared us for the COVID search. And then, I mean, the change was big, but it was five fold. So before COVID we had two million readers or users every month and now we have 10 million, so it was not a huge change, it was not orders of magnitude or anything.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah, I recall all kinds of political leaders going and giving talks in front of their countries and basically pulling out Our World in Data graphs. I was excited for you, seeing that, surely you must have been kind of pleased?

Max Roser: Of course, that was quite crazy to see. I mean, the first time Donald Trump was using our statistics, we were on a phone call, all of us, and then I got a message from a friend like, “Trump is tweeting Our World in Data stats,” and with this polarized discussion in the U.S., I was mostly scared actually, right? I was thinking now we’re part of this battle, and the source of one camp or the other. But then Joe Biden was also using Our World in Data, and so I think that one of the things we’re very happy with is that people from very different opposing camps are all relying on Our World in Data. Even if they disagree, they at least agree on the data.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. What was most challenging about this time emotionally or personally for people on the team?

Max Roser: I think it’s almost always to make a big mistake, to say something that is presented in a way that’s really wrong and misinforms people, that’s for sure the biggest. It was also quite frantic to get lots of feedback from infectious disease experts at the time. That was very helpful. And then it was, I mean, everyone was struggling with the situation in February, March, and the pandemic was spreading fast and people were afraid. Maybe not so much about their own health, or at least I wasn’t, as a relatively young person, but I was obviously scared for my parents’ health and that they stay safe, buy enough beans and rice. And then the work was just very, very long hours. We were all working as many hours as we possibly could. In the night I was sleeping here on the floor just so that we could maximize the time trying to understand what’s happening and trying to get clean spreadsheets out into the world.

Vaccination data set [00:45:43]

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. Are there any parts of the COVID resources that you think were particularly innovative or which you’re particularly proud got built, or maybe that the team as a whole is really proud of?

Max Roser: I think the aspect that we haven’t spoken so much about is the vaccination dataset. And that’s honestly one that I really got wrong. I would have not expected somehow that there would be so much attention being paid to the vaccination dataset, and I would have also not expected that it would be on us to produce this dataset. And I was really wrong on both counts. The vaccinations started in December, and we were all tired. We were all looking forward to Christmas. And then Edouard was suggesting that we should probably compile the vaccination data, since the first person here in the U.K. was vaccinated just then. And I was like, “No, we’re not going to do this. This is just… It can’t be on us.” I was like, “I want to take some time off. I want to see my parents over Christmas. We’re not going to do that. And also surely someone will do it.” And then his point was like, “Well, no one is doing it yet. And also it’s something that’s going to be fine if we just do a weekly update.” That was the point that convinced me: “It’s going to be fine if we do a weekly update.” And then he started by himself. And obviously there was so much attention to it. I think at the beginning, it was just because of this story that Israel was vaccinating so much faster than everyone else, and there was this huge discrepancy. Lots of countries, again, struggle to make their data available. So there was much more focus on it.

Max Roser: And suddenly it became this really full-time job just for him. He was sitting in his apartment in Paris, producing this spreadsheet that everyone from The Economist, The Financial Times, The New York Times, the WHO, the U.S. CDC, everyone is relying on his figures. On the one hand, I think it should, again, not be the situation. On the other hand, I’m really proud of him pushing for that and building this dataset and informing the public about what’s going on with the global vaccination roll out.

Rob Wiblin: How much of that work is just going to a web page for every country that you want to have data on every day and then pulling out the number? And has it been possible at all to outsource that kind of work to virtual assistants or maybe people who aren’t such core members of the team?

Max Roser: Yeah. So to a good extent, this data is pulled in by scrapers that Edouard also built, but to a good extent, it’s still the same problem that we keep on coming back to, that the data is published in obscure ways and then it has to be typed in by hand. And yes, people did get involved also on our GitHub and helped us a lot with pointing us to sources when new vaccination campaigns started, when new sources became available. But that’s also stressful, right? For him in particular because once you are the central data source, the public is also quite demanding. If it’s Sunday morning and the data for Malta hasn’t been updated in the last four hours, you have five emails from Malta about how you have this bias against Malta and how you have this agenda not showing the amazing figures from Saturday in Malta. And that’s also psychologically taxing, right? You try to do your best, but then you get quite a bit of screaming where people see all kinds of agendas in your work that just aren’t there.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. It’s really interesting that people have this sense of entitlement, or it’s because you’ve been doing such a good job that then any way in which you fall short of perfection, people feel like they’re entitled to this incredibly high performance by this team. I mean, admittedly, I guess you’ve raised money from donors in order to do this, and you’ve said that you’re going to have a crack at it, but there’s no particular reason why this is your responsibility more than any other group’s, right?

Max Roser: Yeah. I think it’s both. It’s fine if people demand the best work and want the data to be updated as soon as possible. I think what’s not fair is if people see this kind of agenda, and I think that’s just… It’s maybe also even a bit hard to understand, because if you have only one of these messages come your way, then I can deal with that. But it’s just relentless, right? And you tweet this statistic, like, okay, we say the data has been updated on the vaccination database. Here is the data for 10 countries. And the immediate response is, “Why isn’t Canada shown? Why is Mexico shown? Why isn’t Brazil shown?” And every decision that you make around that is interpreted by someone as some kind of vendetta against a particular country, and that’s just taxing over time.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. That’s something that I wouldn’t have totally anticipated, but I guess when you have an audience as large as 10 million regular readers, then even if 99.99% of people are sane enough to realize that you don’t have an anti-Malta agenda, the one person in 10,000 who thinks that you have a vendetta against them might be particularly motivated to email you, and that becomes an awful lot of people. Hundreds of people harassing you about make-believe concerns.

Max Roser: Right. I sort of don’t want to overstate it, lots of people also take time to just say that they appreciate the effort and that they’re thankful that the work is there. But yeah also maybe I tell the story because it’s not so obvious that this would happen. I would have not expected that this would be one of the issues to deal with.

Rob Wiblin: …the biggest downside.

Max Roser: Yeah.

Rob Wiblin: I remember sometime around maybe June last year I was on your website and I was like, “Oh wow, they’ve done this big update. They’ve restructured it. They’ve got all of these pages. They’ve nailed the COVID-19 thing. I’m so glad that they can probably put up their feet a bit and feel like they’ve done it.” But it seemed from the outside like you just never gave up on trying to find ways of reorganizing things and presenting things more clearly and having more resources. I guess, what was it temperamentally perhaps that meant that you just never accepted that you’d done a sufficiently good job?

Max Roser: Because it’s so obvious that there’s so many ways in which you can do a better job. That it’s online doesn’t allow so many things that you would like to see. For example, one thing is that we have a big problem in all of our work where we have a really large amount of information in the database, but for you as the user, it’s very hard to actually explore everything that is there. For the COVID work we have this Data Explorer where you can perhaps see 50 metrics or so, but we would have even more. And you would also want to see how the death rate compares with the age profile in the country? Or how does it compare with the income of the country? And that’s all not possible. So the really obvious things that should be possible aren’t possible yet. It’s just very obvious for us to keep on going and be better prepared for the next pandemic.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah. I don’t know, as a user you were satisfying my needs, but maybe from the inside you can see all of the imperfections in a way where I haven’t even yet thought about, ways that it could be even more useful.

Improving the vaccine rollout [00:52:44]