Are we doing enough to stop the worst pandemics?

COVID-19 has been devastating for the world. While people debate how the response could’ve been better, it should be easy to agree that we’d all be better off if we can stop any future pandemic before it occurs. But we’re still not taking pandemic prevention very seriously.

A recent report in The Washington Post highlighted one major danger: some research on potential pandemic pathogens may actually increase the risk, rather than reduce it.

Back in 2017, we talked about what we thought were several warning signs that something like COVID might be coming down the line. It’d be a big mistake to ignore these kinds of warning signs again.

This blog post was first released to our newsletter subscribers.

Join over 500,000 newsletter subscribers who get content like this in their inboxes weekly — and we’ll also mail you a free book!

It seems unfortunate that so much of the discussion of the risks in this space is backward-looking. The news has been filled with commentary and debates about the chances that COVID accidentally emerged from a biolab or that it crossed over directly from animals to humans.

We’d appreciate a definitive answer to this question as much as anyone, but there’s another question that matters much more but gets asked much less:

What are we doing to reduce the risk that the next dangerous virus — which could come from an animal, a biolab, or even a bioterrorist attack — causes a pandemic even worse than COVID-19?

80,000 Hours ranks preventing catastrophic pandemics as among the most pressing problems in the world. If you would be a good fit for a career working to mitigate this danger, it could be by far your best opportunity to have a positive impact on the world.

We’ve recently updated our review of career paths reducing biorisk with the help of Dr Gregory Lewis, providing more detail about both policy and technical paths, as well as ways in which they can overlap. For example, the review notes that:

- Policy changes could reduce some risks by, for instance, regulating ‘dual use’ research.

- New technology could help us catch emerging outbreaks sooner.

- International diplomacy could devote more resources toward supporting the Biological Weapons Convention.

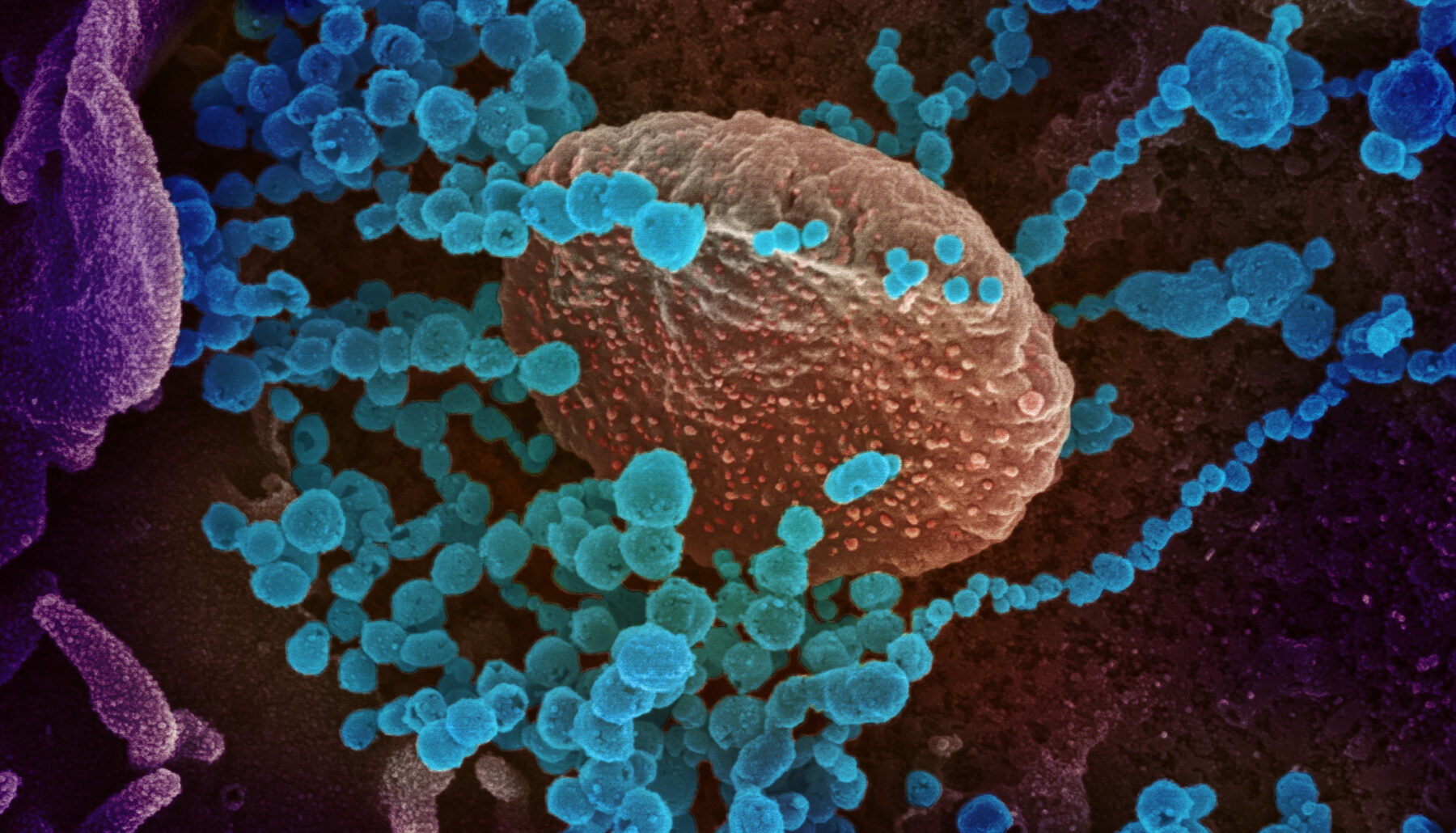

There’s particular reason to be worried about engineered pathogens, whether they’re created to do harm or for research purposes. Pandemics caused by such viruses could be many times worse than natural ones, because they would be designed with danger to humans in mind, rather than just evolving by natural selection.

The Washington Post story linked above suggests some reason for hope. Scientists and experts are raising alarms about risky practices in their field. And according to anonymous officials cited in the piece, the Biden administration may announce new restrictions on research using dangerous pathogens this year.

If executed well, such reforms might significantly reduce the risk that labs accidentally release an extremely dangerous pathogen — which has happened many times before.

We also need to be preparing for a time, perhaps not too far in the future, when technological advances and cheaper materials make it increasingly easy for bad actors to create dangerous pathogens on their own.

If you’re looking for a career working on a problem that is massively important, relatively neglected, and potentially very tractable, reducing biorisk might be a terrific option.

Learn more:

- Problem profile: Preventing catastrophic pandemics

- Updated career review: Biorisk research, strategy, and policy

- Podcast: Dr Gregory Lewis on COVID-19 and reducing global catastrophic biological risks

- Forum post: List of short-term (<15 hours) biosecurity projects to test your fit