Some thoughts on moderation in doing good

Here’s one of the deepest tensions in doing good:

How much should you do what seems right to you, even if it seems extreme or controversial, vs how much should you moderate your views and actions based on other perspectives?

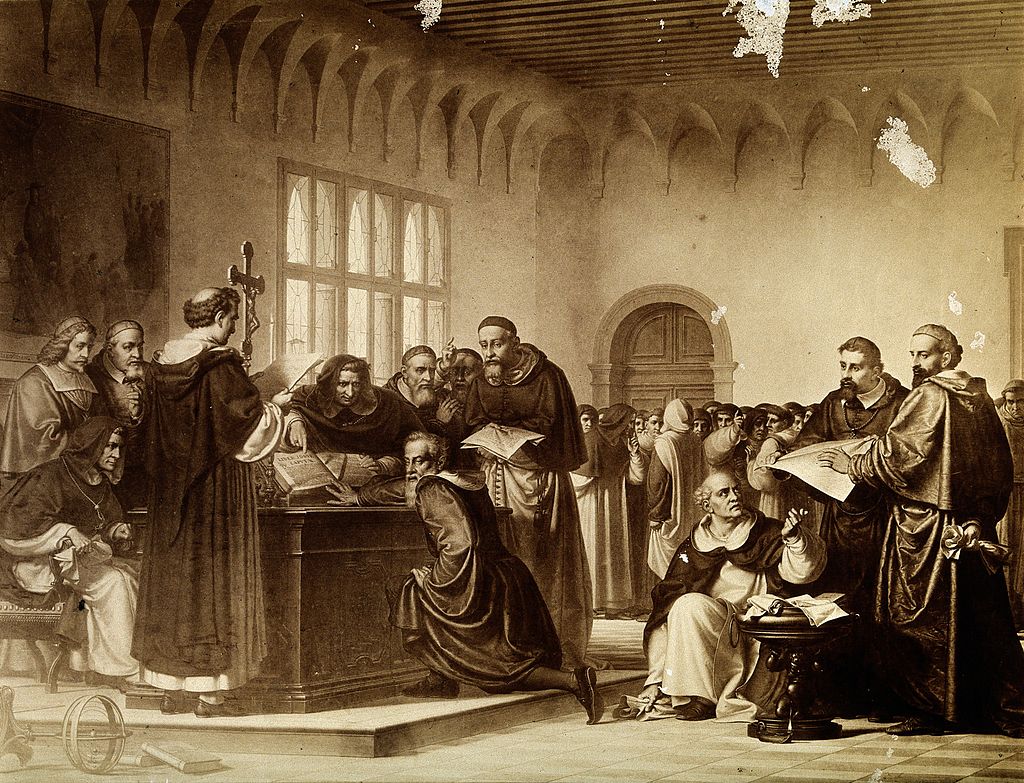

If you moderate too much, you won’t be doing anything novel or ambitious, which really reduces how much impact you might have. The people who have had the biggest impact historically often spoke out about entrenched views and were met with hostility — think of the civil rights movement or Galileo.

Moreover, simply following ethical ‘common sense’ has a horrible track record. It used to be common sense to think that homosexuality was evil, slavery was the natural order, and that the environment was there for us to exploit.

And there is still so much wrong with the world. Millions of people die of easily preventable diseases, society is deeply unfair, billions of animals are tortured in factory farms, and we’re gambling our entire future by failing to mitigate threats like climate change. These huge problems deserve radical action — while conventional wisdom appears to accept doing little about them.

On a very basic level, doing more good is better than doing less. But this is a potentially endless and demanding principle, and most people don’t give it much attention or pursue it very systematically. So it wouldn’t be surprising if a concern for doing good led you to positions that seem radical or unusual to the rest of society.

This means that simply sticking with what others think, doing what’s ‘sensible’ or common sense, isn’t going to cut it. And in fact, by choosing the apparently ‘moderate’ path, you could still end up supporting things that are actively evil.

But at the same time, there are huge dangers in blazing a trail through untested moral terrain.

The dangers of extremism

Many of the most harmful people in history were convinced they were right, others were wrong — and they were putting their ideas into practice “for the greater good” but with disastrous results.

Aggressively acting on a narrow, contrarian idea of what to do has a worrying track record, which includes people who have killed tens of millions and dominated whole societies — consider, for example, the the Leninists.

The truth is that you’re almost certainly wrong about what’s best in some important ways . We understand very little of what matters, and everything has cascading and unforeseen effects.

Your model of the world should produce uncertain results about what’s best, but you should also be uncertain about which models are best to use in the first place.

And this uncertainty arises not only on an empirical level but also about what matters in the first place (moral uncertainty) — and probably in ways you haven’t even considered (‘unknown unknowns’).

As you add additional considerations, you will often find that not only does how good an action seems to change, but even whether the action seems good or bad at all may change (‘crucial considerations’).

For instance, technological progress can seem like a clear force for good as it raises living standards and makes us more secure. But if technological advances create new existential risks, the impact could be uncertain or even negative on the whole. And yet again, if you consider that faster technological development might get us through a particularly perilous period of history more quickly, it could seem positive again — and so on.

Indeed, even the question of how to in principle handle all this uncertainty is itself very uncertain. There is no widely accepted version of ‘decision theory,’ and efforts to make one quickly run into paradoxes or deeply unintuitive implications.

It’s striking that almost any moral view taken entirely literally leads to bizarre and extreme conclusions:

- A deontologist who wouldn’t lie to save the entire world

- Radical ‘deep ecology’ environmentalists who think it would be better if humans died out

- The many counterintuitive implications of utilitarianism

How are we to wrestle with all these different perspectives?

The case for moderation

One thing that’s clear is that the course of action that seems best likely has some serious downsides you haven’t considered.

Partly this is true due to good old-fashioned self-delusion. But even for an honest and well-intentioned actor, there are good reasons to expect this mismatch to happen theoretically, and it has been seen empirically.

Whenever someone proposes an action that seems unusually impactful, further investigation is far more likely to produce reasons that the impact is less good than it first seemed.

Indeed, there are good reasons to think that aggressively maximising based on a single perspective is almost bound to go wrong in the face of huge uncertainty.

The basic idea is that if your model is missing lots of what matters, and you try to aggressively push for one outcome that makes sense to you, it’ll probably come at the expense of those other values and outcomes that are missing from your model. (This idea is closely related to Goodhart’s Law and the AI alignment problem.)

This kind of naive optimisation is especially likely to go wrong when the things that are missing from your model are harder to measure than the main thing you’re focused on, since it’s so seductive to trade a concrete gain for an ill-defined loss.

There are many more reasons to moderate your views:

- Epistemic humility: If lots of people disagree with you about what’s best, and they have similar (and likely greater) information to you, then there’s little reason to think you’re right and they’re wrong.

- Reputation effects: If you take extreme actions, and especially if they turn out badly, you’ll become seen as a bad, reckless, or norm-breaking actor by others. And you’ll also damage the reputation of the causes, ideas and communities you’re associated with. This is an especially big deal since all your impact is mediated by being able to work with and coordinate with other people.

- Signalling and norm setting: Actions we take have direct and indirect effects. One key type of indirect effects that may be overlooked is that they signal to others what’s acceptable, shaping the kind of society we live in. If we send the signal that social norms can easily be broken whenever any given individual thinks of a reason to do so, that’s damaging.

- Character: Humans are creatures of habit. Acting unilaterally or on extremist views in one situation is likely to turn you into the type of person who disregards norms habitually.

- Efficiency arguments: Other people care about doing good to some degree, so truly easy ways to do a lot of good should have been taken already. If you think you’ve found an apparently outsized way to do a lot of good, you should be sceptical of your reasoning.

- Trade: If you don’t think a certain outcome matters that much, but lots of others do, it’s often worth putting some weight on those values, since it will facilitate cooperation in the future.

- The unilateralist’s curse: If everyone working on an issue simply pursues the course of action that makes sense to them, this will lead to the field as a whole systematically taking overly risky actions.

- Chesterton’s fence: Common sense or conventional ways of doing things often contain evolved wisdom, even if we can’t see why they work (also see the The Secret of Our Success).

- Burnout: You have lots of needs, so focusing too much on a single goal is likely to be shortsighted and cause you to become unhappy and give up.

All this means that some degree of moderation is crucial. The difficult question then is to moderate by how much and in what ways.

Striking the balance

After FTX, I definitely feel like moderation is even more important than I thought before. But striking the right balance still feels very hard.

I think the question of how much to moderate may well be the biggest driver of differences in cause selection in effective altruism. People who are more into moderation are more likely to work on global health, while those who are less moderate are more likely to work on AI alignment. (I’m not saying this is a good state of affairs – I think there are ways to work on AI alignment that are compatible with moderation – but it seems likely empirically.)

And the tradeoff comes up in many other places, for instance:

- How much money to spend on saving time even if doing so isn’t normal in the charity sector and could easily be self-serving

- How countercultural vs normal should the your life outside of work be

- Deciding when it’s justified to break norms, be inconsiderate or say unpopular things in order to advance some other important goal

- How possible it is to be more successful than average at conventional things like making money, running an organisation or making predictions

- How much it makes sense to be really ambitious, maximise, and optimise

The spectrum also has many dimensions. Moderation can sometimes look like humility, prudence, pluralism or cooperativeness. Here I’m just trying to point at the broad cluster of ideas, rather than precisely define a single concept.

So, under what circumstances should you bet against conventional wisdom, and how much should you moderate?

Here are some notes about how I currently think about the balancing act in my own decision making, which I think of as attempt to create a cautious contrarianism:

- Use conventional wisdom as your starting point or prior.

- Generally stick with conventional wisdom except for a couple of carefully thought through ‘bets’ against it. You should have an explanation for what other people are missing. Spotting one important way people are wrong is already hard enough, so you need to pick your battles — and being unconventional has costs. So for example, if a startup is launching an innovative product, it should probably just apply best practices in its corporate management, rather than also trying to innovate in how to run a company.

- In working out what these bets should be, don’t just apply a single perspective. Consider a range of perspectives, including common sense, expert opinion and other plausible models and heuristics, weighing them based on their strength. Seek out the best reasons you might be wrong. Remind yourself that you’re very likely to be deluding yourself.

- It’s safest to eliminate any courses of action that seem very bad according to one important perspective. If you can’t do this, proceed cautiously and be open to changing your mind.

- In particular, don’t do anything that seems very wrong from a common sense perspective ‘for the greater good.’ Respect the rights of others and cultivate good character. Yes, in principle there are exceptions to this rule, but if you think you’re one of them, you’re almost certainly not.

- Once you’ve limited your downsides, then seek the course of action with the most upside according to your different perspectives. It’s OK to have your actions driven by one perspective, and to aim ambitiously at long shots, if other perspectives are ambivalent or neutral about it (rather than very negative). Maximise with moderation.

- The more leverage, scale and effect on other people you seek, the more vetting and caution to apply. Chatting about a radical policy with a friend is totally different from pushing for a government to adopt it.

Here are some more notes about the nuances of applying these:

- In general, it’s much more important to moderate your actions (since they could have big direct negative consequences for others) than your views. Indeed, it can be actively good to try to develop unusual views about a topic, since that can add to the collective wisdom. I don’t mean to advance a strong form of epistemic modesty in which you should believe what everyone else believes.

- It’s also useful to distinguish between your internal ‘impressions’ — how things seem to you — and your ‘all-considered view,’ which takes account of the outside view and peer disagreement. It’s fine and often healthy to foster contrarian impressions, but when taking high-stakes action, it’s important to use your all-considered view.

- It’s helpful to think in terms of upsides, downsides, and the median case. Your all-considered view might be that a contrarian position has an 80% chance of being wrong, but if in the 20% scenario acting on it would do a lot of good, and being wrong won’t have big downsides, then it can be well worth betting on that contrarian view — even though it’s most likely to be wrong.

- I’ve framed things in terms of “eliminate big downsides, then seek upsides” since I think that’s a reasonable approximation that’s relatively easy to apply. A more sophisticated version could involve something more like a moral parliament, in which different perspectives have a different number of votes according to your confidence in them, and they collectively bargain to come up with the overall policy. For example, a deontological perspective would be very opposed to violating rights, whereas a utilitarian one will want to do whatever helps the most people. Collectively, this could end up as picking the action that helps the most people but doesn’t violate rights.

All this is pretty complicated to apply, and I’m not sure it would provide bright enough lines to do much to prevent dangerous behaviour in practice, so more work to develop these norms seems useful. We also need other mechanisms to prevent bad behaviour, like good governance — this post is only about one perspective on the problem.

If the main concern is to avoid dangerous behaviour, then I think point (5) about not harming others is most important.

Part of this is because the cases that seem most problematic historically seem to mostly involve dishonesty, rights violations, and domination over others (e.g. totalitarian communism and fascism).

Cautious contrarianism

There are lots of ways to support radical ideas that don’t have these features, such as non-violent protest or academic debate. It’s possible and necessary to have sandboxes, such as academia, where radical ideas can be explored and developed without immediate attempts to apply them.

Or consider the Shrimp Welfare Project. Promoting shrimp welfare sounds a bit nuts at first, but even if shrimp welfare turns out to be entirely unimportant, it’s not doing direct, serious harm to anyone — the likely worst case is that resources are wasted.

People who want to do good are on the safest ground when they can find projects like these. They’re on the most shaky ground when they try to force change on society as a whole.

Another simpler framework would be ‘constrained maximisation.’ Try to do the most good you can, but within the constraints of respecting rights, having a good character and your other important personal goals.

Here are some things that I think follow from cautious contrarianism:

- Have some balance in your life. Doing more good isn’t the only thing that matters. It’s healthy to have a life that’s normal in most other ways.

- Always consider multiple kinds of outcomes — don’t measure everything in terms of QALYs or existential risk reduction.

- Take peer disagreement seriously, especially when others think your actions might cause a lot of harm.

- Don’t surround yourself only with people who share your worldview. Have some friends or colleagues with other views.

- Both means and ends matter.

- It basically rules out individual acts of violence, even if you think it might be justified to respond to a major risk like climate change or AI.

- I don’t identify as a utilitarian — I think there’s a bunch of truth in it, but we’re too uncertain about ethics for me to identify with any single perspective.

- Don’t reinvent the wheel. Apply best practice in most areas of your life.

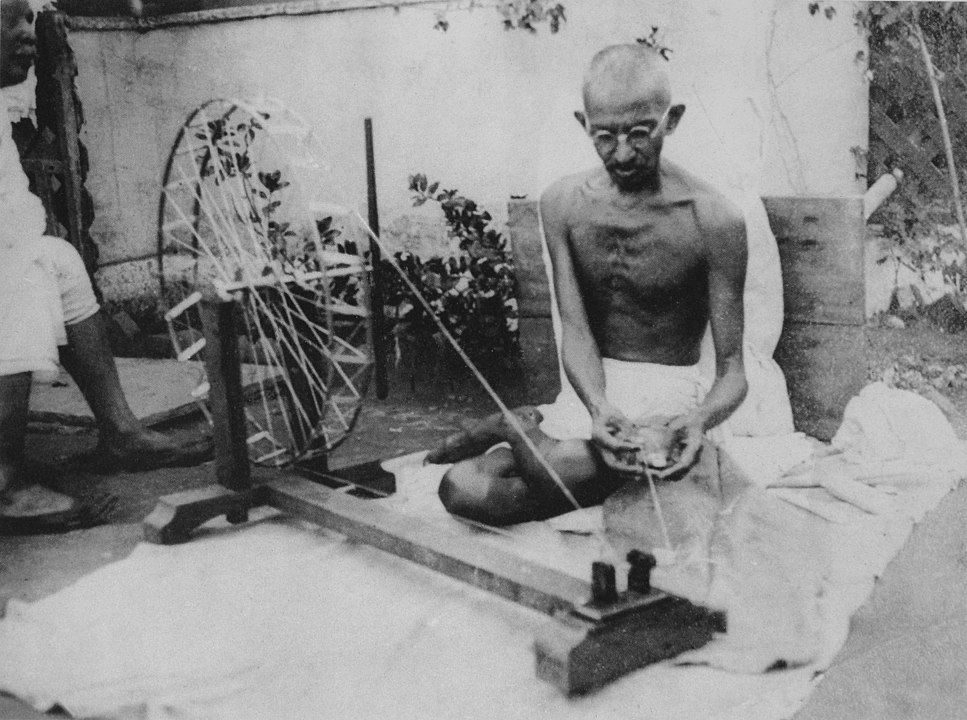

None of these are absolutes. Gandhi definitely didn’t ‘live an otherwise normal life’ and that was part of his influence. It’s plausible there are cases when you should violate these guidelines, but you should do so deliberately, cautiously, and with considered awareness of the downsides.

Some warning signs that could suggest someone isn’t applying cautious contrarianism:

- Willingness to break norms or twist the truth to help their project

- Almost never taking on board criticism or deferring to peers: I don’t think people are obligated to respond to all criticism that’s directed at them all the time, but if you know someone well who’s doing a high-stakes project, you should see at least some serious attempts to engage with the best critics.

- Expressing a lot of confidence about totally unsettled areas like philosophy or topics way outside their area of expertise

- Being a unilateralist, that is, doing things a large fraction of their field thinks have significant harm

- Making rapid and radical changes to their whole life based on a single argument or philosophical view

However, it’s not a warning sign to seriously consider weird ideas with radical implications.

Almost all ideas could lead to crazy, harmful, or weird-seeming implications if pursued to their logical end or allowed to dominate your life. You need to learn the skill of holding multiple conflicting perspectives in mind and coming to some kind of synthesis of them.

Unfortunately there’s no fully principled way to make these tradeoffs, but I think we face something similar in normal life all the time with internal conflicts. Maybe part of you wants to be a parent, but part of you wants freedom. These drives would lead to very different lives, so how do you balance them?

There is no easy answer, and completely overriding either drive would be bad. Hopefully, you can come to some kind of compromise or synthesis that both sides of yourself are happy with.

Likewise, we have to do our best to balance contradictory worldviews and perspectives.

When it comes to effective altruism in particular: doing more good matters and is underappreciated, but it’s not the only thing that counts, and shouldn’t be the only focus of your life.