#43 – Daniel Ellsberg on the creation of nuclear doomsday machines, the institutional insanity that maintains them, and a practical plan for dismantling them

In Stanley Kubrick’s iconic film Dr. Strangelove, the American president is informed that the Soviet Union has created a secret deterrence system which will automatically wipe out humanity upon detection of a single nuclear explosion in Russia. With US bombs heading towards the USSR and unable to be recalled, Dr Strangelove points out that “the whole point of this Doomsday Machine is lost if you keep it a secret – why didn’t you tell the world, eh?” The Soviet ambassador replies that it was to be announced at the Party Congress the following Monday: “The Premier loves surprises”.

Daniel Ellsberg – leaker of the Pentagon Papers which helped end the Vietnam War and Nixon presidency – claims in his new book The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner that Dr. Strangelove might as well be a documentary. After attending the film in Washington DC in 1964, he and a military colleague wondered how so many details of the nuclear systems they were constructing had managed to leak to the filmmakers.

The USSR did in fact develop a doomsday machine, Dead Hand, which probably remains active today.

If the system can’t contact military leaders, it checks for signs of a nuclear strike. Should its computers determine that an attack occurred, it would automatically launch all remaining Soviet weapons at targets across the northern hemisphere.

As in the film, the Soviet Union long kept Dead Hand completely secret, eliminating any strategic benefit, and rendering it a pointless menace to humanity.

You might think the United States would have a more sensible nuclear launch policy. You’d be wrong.

As Ellsberg explains based on first-hand experience as a nuclear war planner in the early stages of the Cold War, the notion that only the president is able to authorize the use of US nuclear weapons is a carefully cultivated myth.

The authority to launch nuclear weapons is delegated alarmingly far down the chain of command – significantly raising the chance that a lone wolf or communication breakdown could trigger a nuclear catastrophe.

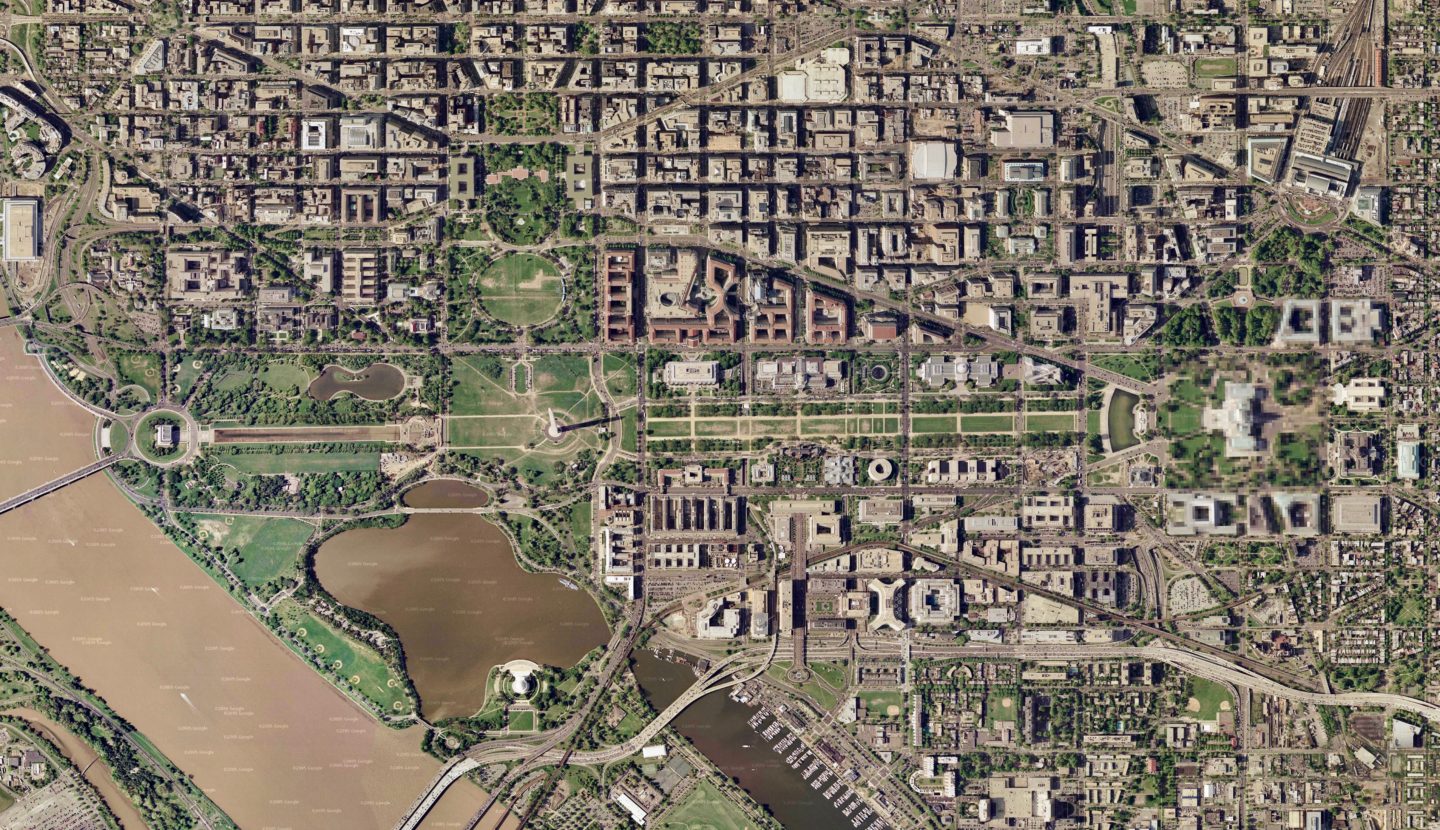

The whole justification for this is to defend against a ‘decapitating attack’, where a first strike on Washington disables the ability of the US hierarchy to retaliate. In a moment of crisis, the Russians might view this as their best hope of survival.

Ostensibly, this delegation removes Russia’s temptation to attempt a decapitating attack – the US can retaliate even if its leadership is destroyed. This strategy only works, though, if you tell the enemy you’ve done it.

Instead, since the 50s this delegation has been one of the United States most closely guarded secrets, eliminating its strategic benefit, and rendering it another pointless menace to humanity.

Even setting aside the above, the size of the Russian and American nuclear arsenals today makes them doomsday machines of necessity. According to Ellsberg, if these arsenals are ever launched, whether accidentally or deliberately, they would wipe out almost all human life, and all large animals.

Strategically, the setup is stupid. Ethically, it is monstrous.

If the US or Russia sent its nuclear arsenal to destroy the other, would it even make sense to retaliate? Ellsberg argues that it doesn’t matter one way or another. The nuclear winter generated by the original attack would be enough to starve to death most people in the aggressor country within a year anyway. Retaliation would just slightly speed up their demise.

So – how was such a system built? Why does it remain to this day? And how might we shrink our nuclear arsenals to the point they don’t risk the destruction of civilization?

Daniel explores these questions eloquently and urgently in his book (that everyone should read), and this conversation is a gripping introduction. We cover:

- Why full disarmament today would be a mistake

- What are our greatest current risks from nuclear weapons?

- What has changed most since Daniel was working in and around the government in the 50s and 60s?

- How well are secrets kept in the government?

- How much deception is involved within the military?

- The capacity of groups to commit evil

- How Hitler was more cautious than America about nuclear weapons

- What was the risk of the first atomic bomb test?

- The effect of Trump on nuclear security

- What practical changes should we make? What would Daniel do if he were elected president?

- Do we have a reliable estimate of the magnitude of a ‘nuclear winter’?

- What would be the optimal number of nuclear weapons for the US and its allies to hold?

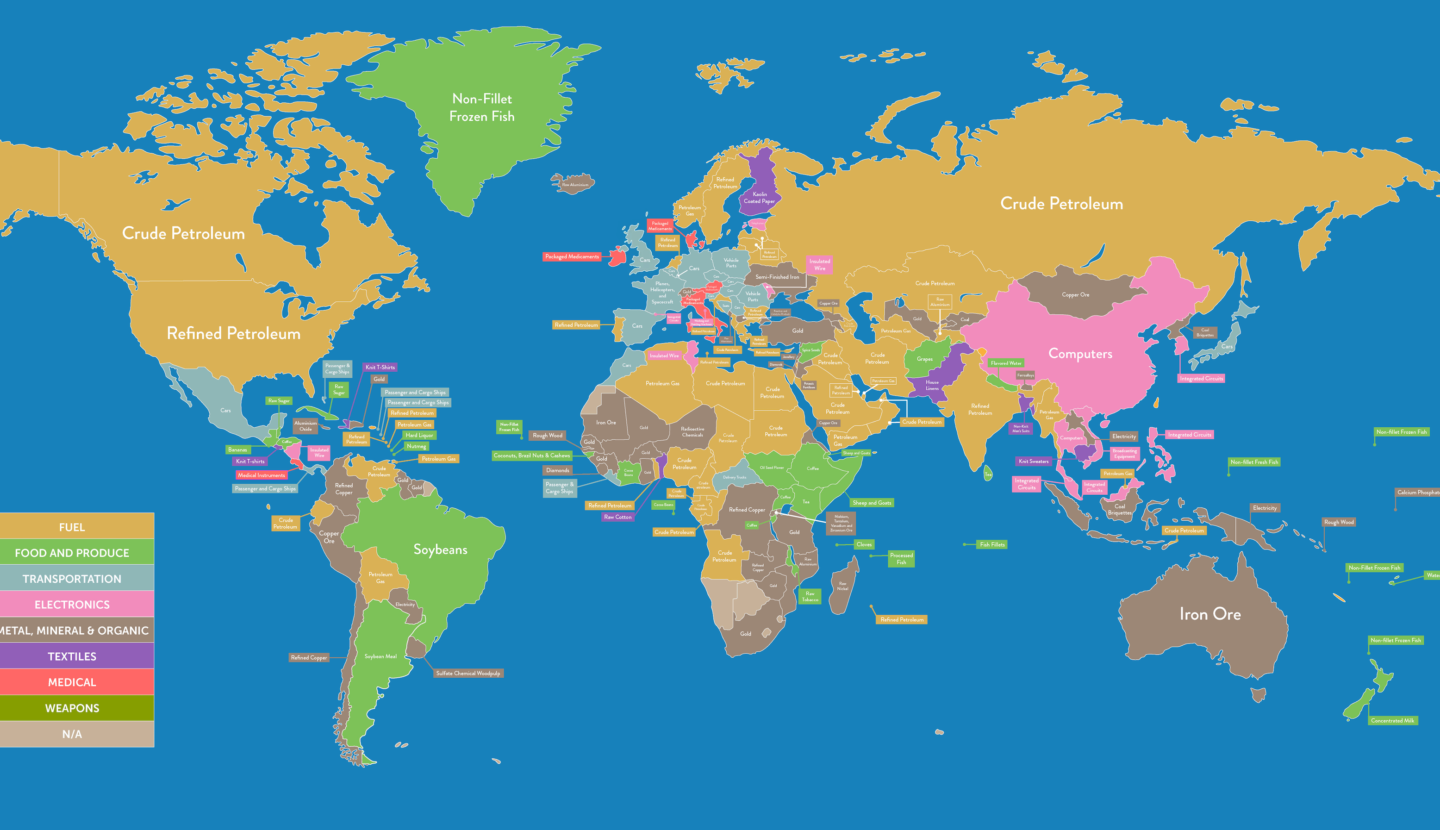

- What should we make of China’s nuclear stance? What are the chances of war with China?

- Would it ever be right to respond to a nuclear first strike?

- Should we help Russia get better attack detection methods to make them less anxious?

- How much power do lobbyists really have?

- Has game theory had any influence over nuclear strategy?

- Why Gorbachev allowed Russia’s covert biological warfare program to continue

- Is it easier to help solve the problem from within the government or at outside orgs?

- What gives Daniel hope for the future?

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

The 80,000 Hours podcast is produced by Keiran Harris.