Emergency episode: Rob & Howie on the menace of COVID-19, and what both governments & individuals might be able to do to help

Emergency episode: Rob & Howie on the menace of COVID-19, and what both governments & individuals might be able to do to help

By Robert Wiblin, Howie Lempel and Keiran Harris · Published March 19th, 2020

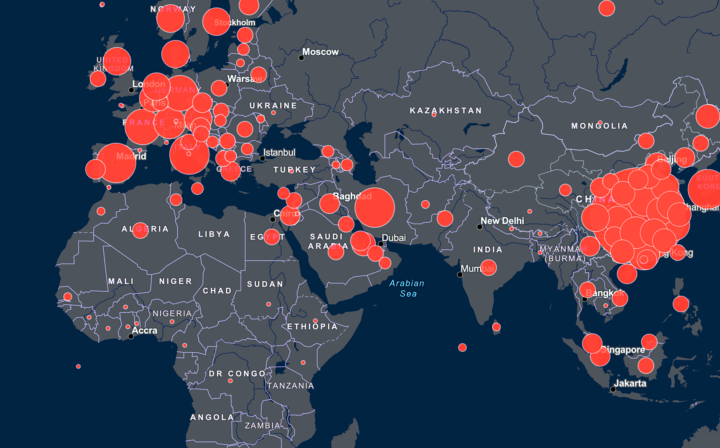

New York Times map of the spread from far back on March 4.

Hours ago from home isolation Rob and Howie recorded an episode on:

- How many could die in the coronavirus crisis, and the risk to your health personally.

- What individuals might be able to do.

- What we suspect governments should do.

- The properties of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the importance of not contributing to its spread, and how you can reduce your chance of catching it.

- The ways some societies have screwed up, which countries have been doing better than others, how we can avoid this happening again, and why we’re optimistic.

We’ve rushed this episode out, accepting a higher risk of errors, in order to share information as quickly as possible about a very fast-moving situation.

We’ve compiled 70 links below to projects you could get involved with, as well as academic papers and other resources to understand the situation and what’s needed to fix it.

A rough transcript is also available.

Please also see our ‘problem profile’ on global catastrophic biological risks for information on these grave risks and how you can contribute to preventing them.

For more see the COVID-19 landing page on our site. You can also keep up to date by following Rob and 80,000 Hours’ Twitter feeds.

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app.

Producer: Keiran Harris.

Articles, books, and other media discussed in the show

Academic resources

- The famous Imperial College London study comparing mitigation and suppression: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand by Ferguson et al. (16 March)

- Critical review of that paper “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions…” by Shen et al. (March 17)

- Reasons why suppression may struggle to work: Analysis of 25,000 Lab-Confirmed COVID-19 Cases in Wuhan: Epidemiological Characteristics and Non-Pharmaceutical Intervention Effects, by Xihong Lin. And Rob lists scenarios under which the UK might need to switch away from its current plan.

- Argument that suppression or containment might be too costly to be worth pursuing: Has the coronavirus panic cost us at least 10 million lives already? by Paul Frijters

- Lessons from containment efforts in Singapore by Lee et al. (13 March)

- Possible Fiscal Policies for Rare, Unanticipated, and Severe Viral Outbreaks from Bill Dupor at the St Louis Fed (March 17) and a breezier set of economic policy suggestions from Greg Mankiw (March 13)

- Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing by Wang et al. (March 3)

- Adjusted age-specific case fatality ratio during the COVID-19 epidemic in Hubei, China, January and February 2020 by Riou et al. (March 6)

- Clinical data on 1,099 patients hospitalized in China before January 29, 2020: Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China by Guan et. al. (Feb 28)

- Basic descriptive analysis of 72,000 patient records reported in China through Feb 11, 2020: Vital Surveillances: The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak in China CDC Weekly

- A Single Ventilator for Multiple Simulated Patients to Meet Disaster Surge by Neyman and Irvan (2006)

Approaches of specific countries

- Why Singapore’s coronavirus response worked – and what we can all learn by Dale Fisher on The Conversation (March 18)

- Which Country Has Flattened the Curve for the Coronavirus? in the New York Times (March 19)

- Without serious action, Australia will run out of intensive care beds between 7 and 9 April by Megan Higgie and Andrew Kahn (March 18)

- How crowded Asian cities tackled an epidemic by Hannah Beech for the New York Times (March 17)

- Korea’s Drive-Through Testing Is Fast — And Free by Anthony Kuhn for NPR (March 13)

- The FDA/CDC coronavirus response is one of the most shocking government failures I have seen in my lifetime by Alex Tabarrok (March 9)

- Website tracking each country’s COVID-19 policy response

Dashboards, models, figures and data analysis

- The best coronavirus dashboard: live updates, cases, death toll, graphs, maps, and compare countries

- Coronavirus Statistics and Research from Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina at Our World In Data

- How many tests are being performed around the world? from Esteban Ortiz-Ospina at Our World in Data

- Epidemic calculator for rough scenario modelling

- Modelling for policymakers: Why you must act now

- Data mapping from JHU GSSE. You can do your own analysis using the source CSVs.

- Great website offering coronavirus projections and comparing cases and deaths to ICU bed numbers made by Chris Billington

- Stay abreast of new developments by reading coronavirus articles at the Financial Times

- A page listing even more COVID-19 dashboards

Projects being undertaken by individuals and groups

- Help with COVID — A compilation of COVID-19 projects looking for volunteers

- Project Open Air — A group working on medical devices, to have a fast and easy solution that can be reproduced and assembled locally worldwide

- Pledge to #StandAgainstCorona – Four important steps can help slow the spread of COVID-19.

- Coronavirus Tech Handbook compiled by Nathan Young

- Crowd Fight COVID-19 appeal for volunteers

- Promoting simple do-it-yourself masks: an urgent intervention for COVID-19 mitigation, by Matthias Samwald and co-authors

- Looking at South Korea’s amazing progress through Rob’s scrappy projection models

- Coronavirus: Tens of thousands of retired medics asked to return to NHS, covered in the BBC

- GM’s CEO Offers to Make Ventilators in WWII-Style Mobilization by Jordan Fabian and David Welch in Bloomberg

- COVID-19 Open Research Dataset from Semantic Scholar

- Offering Funding for COVID-19 Projects by Sam Altman

- COVID-19 Testing Charts by Spencer Chen

- Prepare Now for the Long War Against Covid-19: Fighting the surprise attack should not distract us from the lasting battle by Richard Danzig & Marc Lipsitch in Bloomberg (March 20)

- A hospital begins UV sterilizing masks for reuse

Highly simplified explanations for rapid understanding

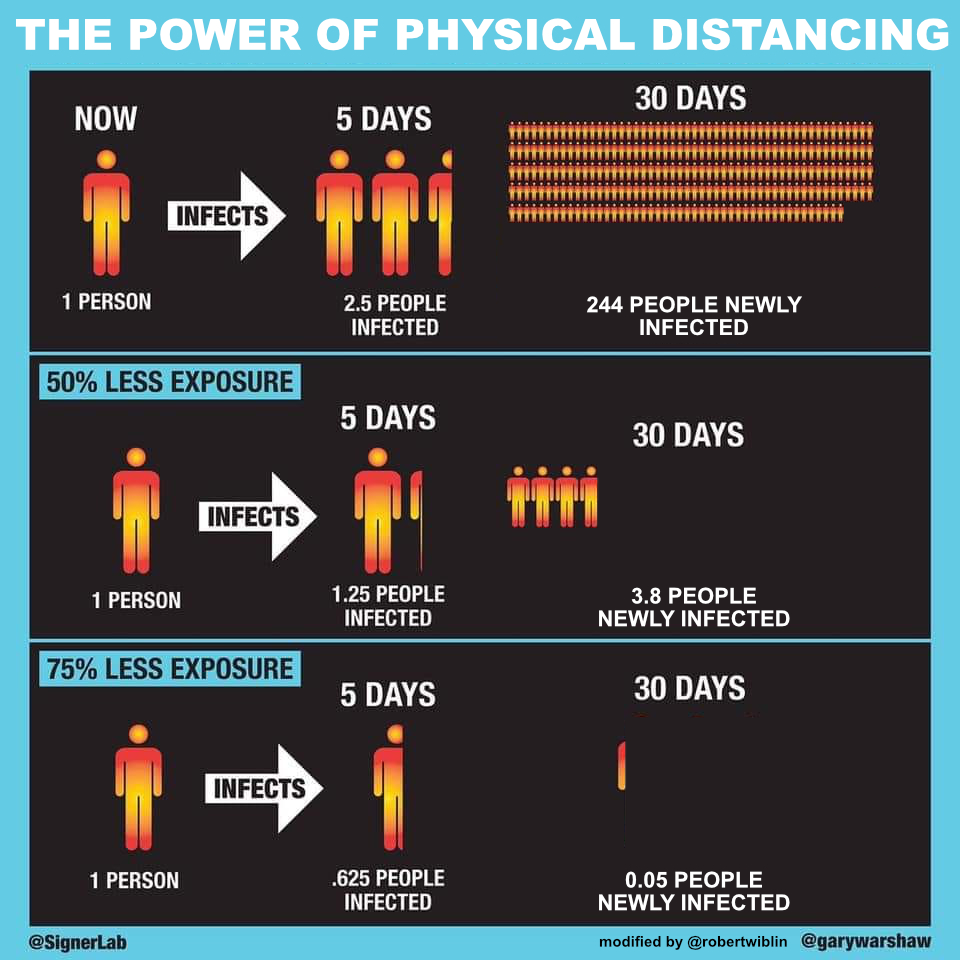

- How to explain the unexpectedly large impact of physical distancing, especially to your less mathy friends and family

- The UK Government’s current strategy to combating COVID-19 in very brief form, and the case in its favour: one, two, three, four

- Viral video that shows you how germs spread

Pharmaceutical and medical interventions

- Handbook of Covid-19 Prevention and Treatment from Hospital with 0% fatality from the Zhejiang University School of Medicine

- Translation of the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia from the Chinese Health Commission (March 3)

- A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19 by Cortegiani et al. (March 10)

- Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro by Liu et al. (March 18)

- Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro by Wang et al. (February 4)

Figures

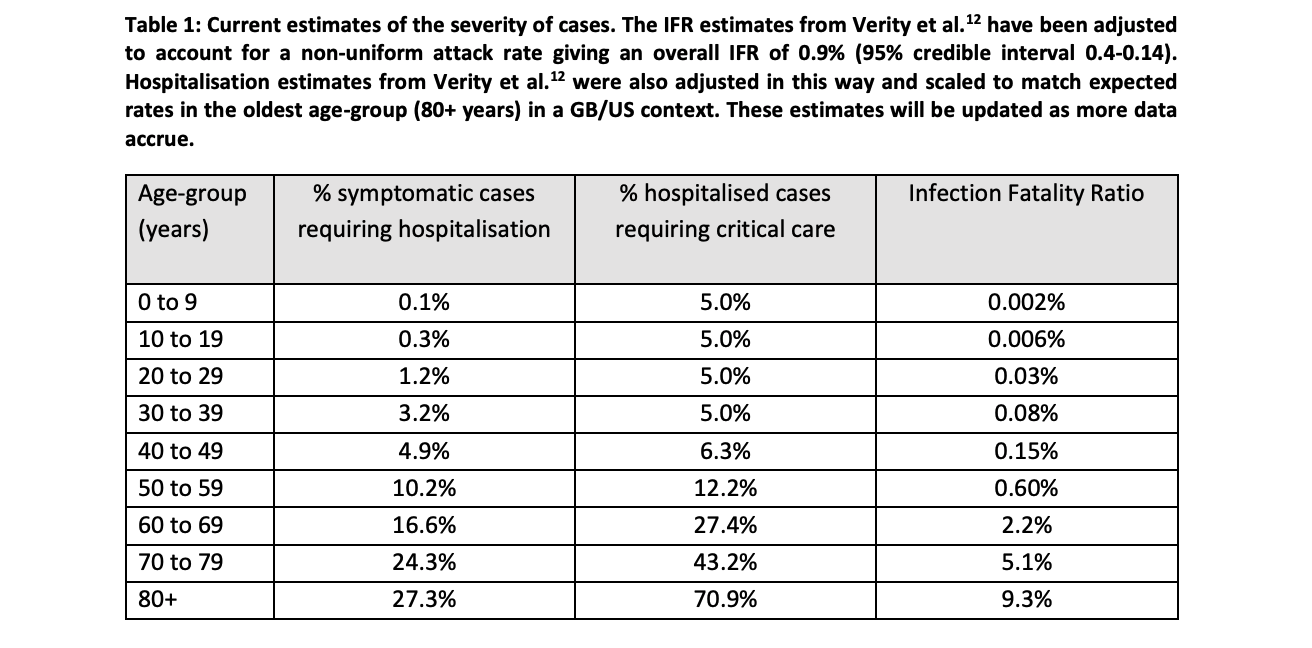

One: Estimates of fatality and hospitalisation rates by age

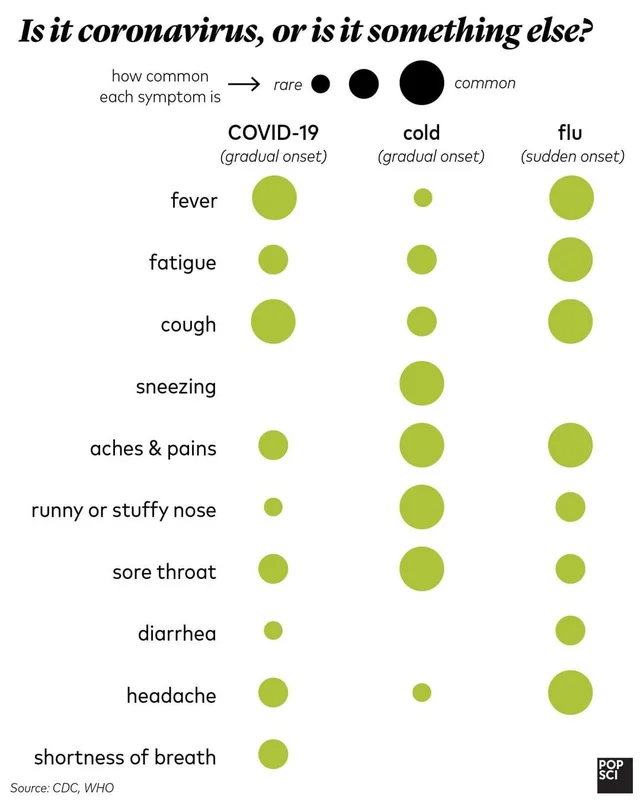

Two: Do you have COVID, or is it more likely something else?

Note: In the time since this graphic was created, we’ve heard preliminary reports that diarrhea and other gastrointestinal issues may be the primary early symptoms for a moderate number of patients.

Three: A simple visualisation of exponential growth

Other news stories lifted from Hacker News that may be useful

- Ten-Minute Coronavirus Test for $1 Could Be Game Changer by Alonso Soto (March 16)

- Government official: Coronavirus vaccine trial starts Monday by Zeke Miller (March 15)

- Italian hospital saves Covid-19 patients lives by 3D printing valves for reanimation devices by Davide Sher (March 14)

- Up to 50% – 75% of cases of Covid-19 could be asymptomatic (March 16)

- COVID-19 Has Caused A Shortage Of Face Masks. But They’re Surprisingly Hard To Make by Emily Feng and Amy Cheng (March 16)

- Is It Time to Rethink Globalized Supply Chains? by Willy Shih in the MIT Sloan Management Review (March 19)

- Alphabet, Walmart join U.S. effort to speed up coronavirus testing (March 16)

- FDA grants Roche coronavirus test emergency green light within 24 hours by Conor Hale (March 13)

- Nvidia calling gaming PC owners to put their systems to work fighting Covid-19 by Connor Sheridan (March 13)

- Face Mask Use and Control of Respiratory Virus Transmission in Households from CDC

Wikipedia on country outbreaks

- The 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic in: New Zealand, South Korea, Australia, United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, France, the United States, Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, Iran.

Government resources

- Relevant publications from the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE)

- UK guidance for households with possible coronavirus infections

- Hygiene promotion poster from Singapore: Let’s all do our part

See also this list of resources from the folks at LessWrong.

Transcript

Table of Contents

Rob’s intro [00:00:00]

Robert Wiblin: Hi everyone, as you might expect under the circumstances, today’s episode is our second impromptu recording about the COVID-19 crisis.

Three quick notes first. In this episode we spend a fair while at the start laying out the general situation that faces us — including where the virus is, in what numbers, how many have died and where, the properties of the virus and the disease and so on.

If, like many people, you’ve been obsessing about this for the last few days or weeks or possibly months, you may feel fine to just skip that section and jump to minute 31 after which we talk about things you’re less likely to know about. If your podcasting software supports chapters, we list 5 of them in this episode.

Second, if you’d like to follow along with my non-80,000 Hours-checked personal opinions as I’m learning about COVID-19 you can please follow me on Twitter at twitter.com/robertwiblin.

Third, we are going to have more articles about COVID-19 which you’ll be able to see when they go on up at 80000hours.org / blog. We’ll also post that as well as other work and articles that we think are interesting at twitter.com/80000hours.

OK, stay safe out there everyone. Here’s me and Howie.

The interview begins [00:01:08]

Robert Wiblin: All right, so we’re here, me, Robert Wiblin and my colleague, Howie Lempel, for what is very much an emergency edition of the 80,000 Hours Podcast to talk about the spread of COVID-19, what the situation is, and what potentially people can do about it, both individuals and governments. How are you doing, Howie?

Howie Lempel: I’m doing well. Happy to be here.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I guess I could be happier to be here. I’m actually out in the country. I left London a week ago. But Howie, you’re camped out in your house in London?

Howie Lempel: Yes, I am camped out and isolating myself at the moment.

Robert Wiblin: Because you have cold symptoms, right?

Howie Lempel: Yes. I started getting cold symptoms. Seemed pretty minor, but we figured be as cautious as humanly possible. And so our housemates went out and got an Airbnb to avoid us and now my girlfriend and I have the house to ourselves as we wait to make sure that neither of us are actually sick.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. We apologize if the audio here is not so good. We didn’t manage to get all of our equipment out of the office and into the different places that people on the team are in time. So this is a slightly more scrappy episode than usual and perhaps even scrappier than our last COVID episode that we did. All right. Well maybe we should start by talking about our qualifications just so people can have some sense of how seriously to take what we’re saying. I guess as many listeners will know, my background is in economics. I also did a science degree. I guess my main qualification to talk about this is, I’ve been paying attention to the COVID situation for two months and I guess the last two or three weeks living, breathing, eating COVID-19 stuff basically all the time. And I guess particularly the last week, I’ve more or less done nothing else. Yeah, Howie, I guess you actually have more of a background in the area than me.

Howie Lempel: Yeah, so my academic background was largely in math and economics and then a little bit of moral philosophy. And then I spent a couple of years in law school in the US and then left to go work for Open Philanthropy where I spent a few years. And when I was at Open Phil, I helped to get our biosecurity and pandemic preparedness program areas started up. We then later handed it off to somebody who is actually an expert, so I should be very clear that I myself am not one. I don’t have any formal training in any of the related areas, but hopefully I picked up something or other in the experience of searching for an expert, making our first couple of grants, trying to learn the space.

Laying out the current situation [00:03:57]

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I’ve gotten a little bit more confident about trusting our judgment in the last few weeks because it seems like things have played out much more closely to what we expected in late January and early February perhaps than what many other people were predicting. Because we had a view that there was a good chance that this could just spread everywhere and get out of control and be a worldwide pandemic, that it could kill something in the order of 1% of the world’s population, that that was plausible. We made, I guess, estimates in those early days about the case fatality rate, the infection fatality rate, the transmissibility, that now all seem kind of consistent with what we’ve seen over the last six weeks.

Howie Lempel: Yeah. I haven’t gone back and re-listened, but that all sounds just about right to me. I guess the thing that feels most surprising to me, relative to what I believed then, is how good of a job China has done of containing the disease in mainland China. I think that that was something that I hadn’t expected with a respiratory disease that a country so big would actually be able to shut down an outbreak that had already spread so far.

Robert Wiblin: Yes, that was quite surprising to me. And I guess initially when they started reporting such a trail off in new cases, I was suspicious that this could be a measurement error somehow. I think we did say at the time that it was just we were in uncharted waters in terms of the severity of the shutdown that China was doing. That basically no one else had done this before. So we just didn’t know what the effect of it was going to be, but it was more than what I thought. Basically, it seems like China, to a large extent, has control of the pandemic for now, and the question is, will they be able to maintain that while returning to something resembling normal life?

Howie Lempel: Yeah, that seems right.

Robert Wiblin: All right, let’s move on and just give people a sense of the state of play. As of, I guess we’re recording at, you have to say the time of day these days, recording at 16:30 in London on the 19th of March. And as of now, we’ve got about 225,000 confirmed cases globally. But in reality, we would guess that at least there’s 10x that number of actual people infected worldwide, potentially quite a bit more than that. About half that number is in China, where we now think that the pandemic is largely controlled as we said. So most of the growth is occurring outside of China and we’re getting about 15 to 20,000 new confirmed cases a day with a special concentration in Europe in particular; I guess France and Spain. Sorry, Italy is actually at the top. Some in Switzerland and Germany and the UK. But they’re reporting particularly large increases. And we’re seeing, I guess, about a 15 or 20% increase day-on-day of out-of-China cases. Is there anything you want to add to that, Howie?

Howie Lempel: Did we also catch Iran?

Robert Wiblin: Oh, sorry.

Howie Lempel: Which is another country that has a really high caseload.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, sorry. It seems like there’s an enormous number of cases in Iran, but I think their testing capacity is lower, so it shows up less if you just look at the confirmed case increase or at least it did when I last checked, if I recall.

Howie Lempel: Well, I guess it has the third most total confirmed cases after China and Italy, so it’s up there.

Robert Wiblin: So it’s up there. Nice. Okay. Yeah. Just checking on Iran, they’ve got 18,400 confirmed cases, 1,300 deaths or so. And I guess in the last day they reported, let’s see, about a thousand new cases, which is a 7.3% increase. Yeah, it looks like the case increases have been linear for quite some time, which I suspect is because of bottlenecks in testing rather than the cases actually growing at a linear pace. Anyway, yeah, globally we’ve got about 9,300 people reported dead, which would give us a case fatality rate around 4%. At least that’s what the figure was yesterday.

Howie Lempel: Going quickly back to the data in China, it looks like now just about a third of current cases or of total confirmed cases are in China. I think that there’s this perception that this is sort of like a Chinese virus, a Chinese disease, that sort of started to affect everybody else. And it seems worth noting that that’s just not the case anymore and that most of the confirmed cases at this point are happening outside mainland China.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, at this point, China should be stopping anyone from coming in rather than the reverse. They have a lower density of cases than many other places. Yeah. Okay. In terms of deaths, we’ve got, I think, put these numbers in yesterday, 9,300 deaths globally, which was about a 4% case fatality rate based on the number of confirmed cases at the time. Keeping in mind, of course, many people were confirmed recently so they won’t have passed away yet. And at the same time, we think we’re only capturing a small fraction of all of the cases that are actually out there. So that kind of raw case fatality rate doesn’t tell you all that much.

Robert Wiblin: But we can see interesting variation between countries. In South Korea, they’ve had 8,400 confirmed cases and done the most stringent testing regime of anywhere outside the Bhutani Gulf States. And they had a case fatality rate of 1%, so they’ve had 84 deaths out of 8,400 cases. By contrast, in Italy, they’ve had about 36,000 confirmed cases and almost 3000 deaths, which just translates to about an 8.3% case fatality rate. So an eightfold difference there, which I think is partly probably due to the different demographic breakdown that Italy is an older country. But also I think it suggests that we’re capturing a far smaller fraction of all the infections as confirmed cases in Italy. And you see that in the different confirmation rates within the testing. So in Korea, they’ve got, I think a 3% confirmation rate on tests while in Italy, when I checked yesterday, it was more like 20-21% which was among the highest in the world, which suggests that there’s a vast number of cases in Italy that are not being tested for. And if they were able to test more people, they’d find that there is way more people who have it than what is measured.

Howie Lempel: Yep. And in those cases, usually the people who do get tested are the people with the most severe cases. That’s a second mechanism for why you end up overestimating the case fatality rate.

Robert Wiblin: Right. So last time I think we pointed to some piece of research that suggested that the best estimate of the infection fatality rate, that is, the probability of someone dying if they actually get infected rather than if they’re confirmed through some test to be infected was about 1%. Where are we on that research now, Howie?

Howie Lempel: Yeah, I think the best answer is that it hasn’t changed all that much. It’s more complicated now because there are more estimates out there and people are now trying to do estimates that are sensitive to the differences between places because we don’t expect the infection fatality rate to be the same in every country depending on their medical system, depending on what interventions they choose. But a couple of recent estimates were 1), coming from a top modeling group at Imperial who used a 0.9% overall infection fatality rate as their assumption for what the infection fatality rate would be in Great Britain if Great Britain didn’t take any more measures than it currently is. So that’s sort of like a world where the hospitals really do fill up and get overwhelmed. And then another estimate that I thought was particularly good based mostly on data in China found a 1.6% overall infection fatality rate. So I think you’re going to see most of the estimates somewhere in that 0.8 to 1.6% range if you’re talking about basically situations that look fairly similar to the situations that we’ve seen so far.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. So that infection fatality rate is going to vary a bunch based on whether the hospital system is overwhelmed which is a big concern that people have. Do you have any sense of what the range would be between getting it early when the medical system is functioning well to getting it during a peak when most people are going to struggle to get medical attention?

Howie Lempel: Yeah, I think it’s really hard to say. So the big constraints that we know of are going to be the number of ventilators that they can use. Basically, if your lungs stop working, they can mechanically sort of breathe air into you in ICUs. And so that’s a life saving procedure. And then the people to operate those ventilators. And our best guess right now is that those are sort of the two main constraints. It doesn’t seem like almost any country is going to have the capacity to treat everybody who needs access to these ventilators if the pandemic is just allowed to sort of go forward without any major interventions.

Howie Lempel: And so a question is, well, how high exactly the case fatality rate are we talking about if we don’t do that? And it’s really hard to estimate because you might want to compare to the data we have from China where they had an infection fatality rate of about 1.6%. But we don’t exactly know how much access to this equipment those patients had. So I think best guess is that moderately crowded hospitals are going to lead to infection fatality rates in the 1 to 1.6% range. And then as they get much more overwhelmed, you’re going to sort of see them higher than that. And if you can get them less overwhelmed, you’re going to see them go down. So that’s my sort of really high level take on it.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, so that sounds about right. I guess in Hubei, even though there was a ton of cases, they benefited from the fact that they could send medical staff and equipment from the rest of China, which I guess meant that things were kind of in an emergency situation but not completely overwhelmed necessarily and they were famously building those hospitals incredibly quickly. But if it was allowed to just overrun entire countries or entire continents, then everyone would just be in the same impossible situation.

Howie Lempel: Yeah. I don’t have a sense like just quantitatively how much exactly, and at what point the help from other provinces ended up making a big difference in Hubei.

Robert Wiblin: I don’t know either. You were saying if it spreads uncontrolled, then not everyone will be able to get that equipment. It seems like if it’s spread uncontrolled, approximately nobody who needed equipment, like roughly 0%, would be able to get medical assistance, which I guess is why this seems like it’s just such an incredible emergency potentially. Like the biggest global emergency that we might live through, potentially. That something has to be done to stop this progress. Otherwise, we could see fatality rates above 1% of the whole population.

Howie Lempel: Yeah, that seems right. And I guess when we’re talking about running out of ventilators, I think it’s often easy to slip into thinking about rich countries and the fact that they do have some spare ventilator capacity. And you can imagine them scaling it up and then there’s a whole bunch of countries that are going to have even less capacity than the places that most of the models are coming from. So should be even more worried there.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, it’s interesting. We might get to talking about those countries later in this episode, or might have to save it for another episode, because I haven’t done enough background research to understand what the situation is in India. I guess one thing that those countries have going for them is sometimes that it’s quite a bit hotter, which apparently can make it harder for the virus to spread. But I guess we also just have incredibly poor data in many of these countries to indicate what is the level of penetration of the virus at this point.

Howie Lempel: That’s right.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. So yeah, severity of the illness. What fraction of people are asymptomatic? What fraction of people will have a serious flu, and what fraction of people is it life-threatening for?

Howie Lempel: Yeah. So I think we don’t yet have excellent data on any of this, but I can give you a sense of what’s out there. So on what percent of patients are asymptomatic, one of the best measures that we have is we can look at data from the Diamond Princess, which was this cruise ship that had a terrible outbreak. And a very high percent of the people on the cruise ship ended up getting tested. So they got tested even if they were asymptomatic. And we can then look at, okay, out of all the people who are infected, how many of them were asymptomatic. And depending on how you measure, I think you end up getting something like 45% to 55%. The issue there is that it has a fairly long incubation period. So from when you get infected until you start getting sick, even if you’re eventually going to be symptomatic, there’s going to be a long period of time. So we don’t know how many of these asymptomatic people from the Diamond Princess, once they left the ship, ended up developing symptoms. So you can sort of think of that number as like an upper bound.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, there’s also some more recent report of, I think, 3000 or so people who were tested in an Italian village where they found about 50 to 75% they estimated were asymptomatic currently. But that’s suffers maybe even more severely from this issue that many of them will develop symptoms in future. And it’s very frustrating that more followup wasn’t done on all of the people from Diamond Princess. It seems like a massive oversight because we could have gotten a much higher quality dataset there.

Howie Lempel: Yeah, I’ve actually been looking into this and it seems possible there’s some data out there. Worldometer seems to have some follow up, but it’s just entirely unclear where it comes from. So I don’t know how thorough it will be or anything like that.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I like Worldometer as a website and it is incredibly frustrating how poorly they source their data. Usually when I’ve looked into it, it is real. They’re not just making stuff up. But you have to hunt around for where they’re getting it from.

Howie Lempel: Yeah.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. So that’s the asymptomatic cases. How about the severity breakdown?

Howie Lempel: Yeah, so the heuristic that people have been using has been something like 20% of cases are severe.

[Ed: After this episode was released, we learned that some prominent studies use a weaker definition of ‘severe.’ Our heuristic is now to think of ‘mild’ as everything from asymptomatic through ‘flu/pneumonia that’s at the borderline of requiring hospitalization.’

We’re generally thinking of severe as ‘flu/pneumonia that requires hospitalization and oxygen’ to ‘in need of mechanical ventilation in an ICU.’

Definitions vary across studies, though, so it remains important to track exactly what definition is being used.]

Howie Lempel: And severe means, in my opinion, like actually quite severe. And it depends by the study, but usually it’s defined as something like needing to go to an ICU because you’d need a ventilator to assist your lungs. That’s a pretty serious situation. A bunch of people who end up in that situation don’t end up making it. There’s some chance that you’ll end up with longer term damage from going through that. But it is good that it’s only about 20% of people as far as we know. And then the other 80%, if that’s right, would be a combination of people who are seriously ill, who maybe have pneumonia but pneumonia that’s not bad enough to get them put into an ICU to people who have flu-like symptoms to people who are nearly asymptomatic or asymptomatic. And so that’s sort of the range of severity. And I don’t think we have a lot of precision within that about exactly how it breaks down between those categories.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, so this might be a good time to talk about this table that we found in this muddling from Neil Ferguson’s group at Imperial College London, which has had a big influence on the conversation over the last few days. In table one, they have infection fatality rate estimates by age, from Verity et al., a paper that I have not looked at, at all. And so they try to estimate using the percentage of symptomatic cases that would require hospitalization, which I guess gives you a sense of the fraction there that are critical. And then they also try to break down the percentage of hospitalized cases that require critical care, which I guess, in this case, is something like a ventilator and potentially a full staff member to monitor them.

Robert Wiblin: So for people in our age group, which is thirties, which is what I looked at first perhaps unsurprisingly, they had a 3.2% requiring hospitalization estimate. Five percent of those would require critical care, and then they had an infection fatality ratio estimate of 0.08%, so about one in a thousand. Interestingly, as you go below that, all of those rates decrease a lot. Even for young children, it seems like the disease is affecting young children much less than even middle-aged people to the point where it seems like it’s very rare for someone under 10 to die. I guess possibly newborns could be affected worse. But people under 30 don’t need to worry so much for themselves. They mostly need to worry about the fact that they’re going to infect and kill other people.

Robert Wiblin: These numbers ramp up a lot for people who are older though. So if you’re 40 to 50, then you’ve got a 5% chance of requiring hospitalization. 50 to 60 it’s more like 10%. 60 to 70 it’s 17%. 70 to 80 it’s 24%. And then 80 plus, they estimate 27%. And similarly, the infection fatality ratios that they estimate go from 0.1% for you and me Howie, to 0.15% for people in their forties. 0.6% for people in their 50s. 2.2% for people in their sixties. 5.1% for people in the 70s and all the way up to 9.3% fatality rate for people in their 80s. So very severe numbers potentially for people who are older than us.

Howie Lempel: And do we have a sense of why the numbers are differing so much by age?

Robert Wiblin: Interesting. Yeah, I don’t know off the top of my head. I guess in general it seems like the flu affects people who are older potentially a lot worse, but I’m not sure exactly why that is either.

Howie Lempel: Yeah. I guess one theory is that it actually is specifically to do with age and I think that’s certainly playing a role. I think lung capacity gets a bit worse as you age. Another big proportion of it I think is that people with pre-existing conditions have done a bunch worse.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah.

Howie Lempel: And older people are much more likely to have additional health issues. So that might give some sense that a particularly healthy person in one of the older age groups might expect outcomes that look a bit different from the ones here.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Unfortunately, I still have not seen a multivariate regression or a cross tabulation of the fatality rate by both age and pre-existing conditions, which would be extremely helpful to have because let’s say that you’re in your 70s, but you have no heart problems, no lung problems, no other health conditions. It could be that your infection fatality rate could be quite low, but unfortunately no one has yet done that analysis, at least, I haven’t seen it yet.

Howie Lempel: And then I guess a really scary other option for why the infection fatality rates get so high for people who are older. So we’ve started to hear some really scary reports about the triage decisions that doctors are having to make. And one of the main ways that they make those when there aren’t enough ventilators for the number of people who need them, sort of look at expected healthy life years going forward. And so it may be the case that young people are just getting first access to the ventilators that everybody needs to stay alive.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I guess there’d be two things there that they might considering. One is, the number of years of healthy life that they have left, but also their chances of surviving. That potentially if the chances of someone making it just drops too low, then they decide that they have to prioritize someone else who has a better shot.

Howie Lempel: Yep.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. So what do we know about how it’s caught? Do we know more than we did a month and a half ago?

Howie Lempel: My sense is that we don’t know more than we did a month and a half ago. So I think what we know is that the virus will stay on certain surfaces like steel for up to three days, although it degrades over that period of three days. At the end of three days, it’s going to be very little left.

A recent study showed that the virus could remain viable in the air for several hours when a mechanical device was used to keep it suspended as an aerosol. In contrast to what we suggest in the episode, the study did not show that the virus could remain suspended in the air on its own.

Howie Lempel: It seems like it hangs in the air in an ideal laboratory condition up to like a few hours, although even there it degrades really quickly. And then we can take that and then we can take what’s known about how people have gotten sick, who their contacts have been, and sort of make some guesses. So the best guess that we have is that most of the transmissions are happening through a couple of mechanisms.

Howie Lempel: One of them is through droplets. That’s when someone coughs and the droplets that come out directly land on someone else. Another mechanism that seems likely to be playing a big role is fomites. And so that’s when someone gets some virus particles. Maybe they cough into their hand and then they touch something. Now there’s just virus particles lying on that thing. Then someone else comes by, touches it, now they have virus particles in their hand. They touch their face and they get infected. So that seems like another potentially major mechanism. And then there’s direct contact. And so that basically means that if you shake hands with somebody who is sick and it’s reasonably likely that they touched their face fairly recently, it’s reasonably likely that you’re going to touch your face after it happens. And so the virus sort of gets transferred and you get sick that way.

Howie Lempel: So those are the ones that we have the strongest consensus on. Other possibilities, one of them is fecal-to-oral transmission. There’s some evidence that some of that is happening. So that can happen, for example, if you’re in a public bathroom: you flush the toilet and if the seat’s not closed, that flush can sort of throw a whole bunch of microscopic aerosol particles up into the air. And if some of those are dangerous, you’re exposing yourself to those.

Howie Lempel: And then another possibility is that some of it is going through aerosol transmission, which is when someone coughs or even maybe when someone spits or breathes, they sort of expel out even small droplets of water that are able to hang in the air for a while. And those can sort of travel farther and lasts longer. And so when you hear about staying six feet away from people, part of what’s going on there is it’s sort of a guess at how far those aerosols might go, in case the aerosols are driving some of the infection. I haven’t seen any strong evidence, but the thing that everybody seems to believe, which is very unlikely to be the case, is that the virus is actually airborne in a sense that virus particles themselves just stick in the air and stay there for hours to days and can fly more than six feet. So as far as we know right now, there’s no reason to think that.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. How controversial is it that just merely breathing and then someone being six feet away, or I guess less than six feet away, that you can catch it that way without someone coughing? Do many people think that’s definitely the case?

Howie Lempel: This feels like I’m a bit outside of my area of knowledge. My read on what I’ve heard from the virologists, epidemiologists and doctors I follow on Twitter is that people mostly say they don’t think that just being breathed on is where most of the transmission is happening. But it’s also just absolutely possible that some virus is being expelled when that happens. And I think nobody would be shocked to learn that some substantial amount of transmission turned out to be happening that way, is my read of the situation.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Okay. It seems like there’s been a lot of messaging around washing hands and not touching surfaces. And I wonder why there hasn’t been more of a focus on covering up people coughing, because I think there’s good reasons to think that in public spaces, where people are moderately crowded or even in say a supermarket, someone coughs and then those droplets hang around for a while and then just people around you could pick up the illness. I suppose maybe it’s somewhat harder to deal with and in the West we don’t have as much of a culture of wearing face masks that might help to protect against that. But I guess I would like to see more work on that because I expect people have already picked up the hand washing message quite a bit.

Howie Lempel: Yeah, I don’t know why it’s been less of a message. I guess part of it is it might be just harder to build the habit. So it comes out of nowhere. Part of it might be that actually sneezing into your elbow still doesn’t block all of it and maybe it’s only somewhat effective. Yeah, but I guess I’m not entirely sure why that is.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. So the incubation period we think is what, two to 14 days with a handful of outlier, unusual cases. But typically people develop symptoms three to five days after being exposed to the virus. Is there anything to add on that?

Howie Lempel: No. I think people should have five days as the average in their head, and they should think that after 14 days it’s quite unlikely that someone develops it.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. And how long do people stay sick for?

Howie Lempel: We’ve seen lots of data on this and it differs by the sample you’re working with. But if you had in the back of your mind about two weeks if your case is not severe. So basically if you don’t end up needing to be hospitalized, or need to be hospitalized, but it’s fairly minor in that category. If you’re thinking two weeks around, don’t be surprised if it’s a bit longer than that. And then severe, I think, can last somewhere between three weeks and six weeks.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I’ve seen figures suggesting that people who need intubation or people who need medical assistance to help them breathing could potentially require that for several weeks at a time, which was more than I was thinking. And suggest that they’re going to have potentially symptoms for a long period of time as they try to recover.

Howie Lempel: That’s right.

The importance of isolating yourself [00:30:32]

Robert Wiblin: Okay. That’s the scene set. Let’s move on to think about what we think people should be doing or at least the basics of what people should be doing which, in my view, in most places right now, certainly most places our listeners are, is self isolation to stop transmission. Basically, I’m a supporter of everyone who can stay at home, without society collapsing in their absence, should be staying at home. That means no eating out, no going to clubs, no socializing in large groups, no parties. The things that seem least harmful if you need to get out or not be alone is walking alone either outside or in one-on-one situation in a non crowded area or meeting someone one-on-one in your house without having contact with others. Those create much less of a risk of transmission than people being in crowds. Is there much more to add on that, Howie?

Howie Lempel: Yeah, I guess I agree with everything Rob said and then just sort of want to acknowledge the reality that self-isolation is just not a possibility for lots of people. People who have to go to work, people who are doing critical jobs. And so I guess isolation makes it sound like a binary. And what we actually most care about is physical distancing than social distancing. So you know, to the extent that you can create fewer close contacts between you and other people by taking any of these steps, you’re reducing the likelihood that you get sick. You’re reducing the likelihood that if you get sick, you pass it on to others.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Fortunately it looks like government policy is coming along to provide income support to people or relief on their rent or on their mortgage payments or bills so that people can potentially stop working even if they are not in a salaried job where they might continue to be paid anyway. And I think that that is something that we do desperately need. That everyone who can stay home and everyone who society can kind of pay to stay home should be doing that at this point. At least in countries where we know that the virus has reached in any significant numbers. You’re exactly right. It’s about physical distancing, not social distancing. So if you can talk to people on Skype, get on the phone, hang out with people that way, then that’s completely fine.

Robert Wiblin: It might be worth us explaining why we think it is important for people to take what might seem like a drastic step to them if they haven’t been following this for several weeks. And I guess that’s just that if each person who has this transfers it to 2.5 other people, then it’s just going to explode. The case numbers are going to explode exponentially. And the hospital system is going to be completely overwhelmed.

Robert Wiblin: If we managed to cut down the number of contacts that people have by 50% or 75% by getting them to mostly just stay in their house and socialize with no one or just with the same few people repeatedly, then rather than have the case numbers explode, we can actually have new cases decrease as we’ve seen in some countries. Potentially we can have the virus go into recession in a sense and then we can begin to loosen up those restrictions and return to normal life hopefully without the virus then coming back and creating an enormous peak in cases that would just overwhelm the hospital system and society as a whole. Anything to add on that, Howie?

Howie Lempel: No, that seems right to me.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. So there’s this interesting phenomenon that you may not know many people who have caught COVID. You may not know anyone who’s died of it yet. But we have to implement these quite stringent physical distancing measures before that happens. If we only implement them at the point when you’re likely to know someone who has it or even someone who’s died of it, then it will be far too late. And we would have to engage in this physical distancing for a very long period of time. Or it could just be that it’s too late for that to function, to stop the virus from spreading to a vast number of people. It’s just the nature of exponential growth that things are picking up so fast that the only way to maintain control is to do it while you know one in a thousand or ideally fewer people have caught the virus yet.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. So some other advice that we might be able to offer that is fairly straightforward is that if you start getting symptoms of illness, you need to rest up. And it’s much more important than usual for two reasons. One is let’s say that you are getting a cold or the flu. This is a really bad time to be getting that for your own health because it’s possible that you will then catch this other much more serious virus later and you ideally don’t want to have two respiratory illnesses simultaneously. So you want to get over this initial thing, if it’s not COVID, as quickly as possible.

Robert Wiblin: Secondly, if you do have COVID, there’s a risk that it could become serious. If you say just keep working or you don’t rest sufficiently to cure it or to clear the virus without having serious symptoms, then you could end up needing to go to hospital, end up needing medical attention and in the current environment if they’re treating you, they may well not be treating someone else so you’re potentially imposing a huge burden on someone else who then won’t be able to get a respirator or won’t be able to get medical attention because you didn’t stay in bed. Because you didn’t take care of yourself. So strong recommend on listening to what your mother told you when you were growing up and resting if you feel ill.

Robert Wiblin: I think another thing that you can do that is good for society and good for you is to stop smoking. I don’t know what the exact data is on whether smokers have higher fatality rates here. I haven’t seen the latest on that but common sense would suggest that if it’s like other respiratory illnesses, that smoking is going to be an aggravating factor. More generally, I’m trying to get as much sleep as I can and just stay very healthy so that if I do get sick, I’m starting from a better base of health.

Robert Wiblin: And just in general, keep in mind that this is a war scenario for society. It’s a very serious issue and recklessness, going out, socializing in large groups: these are actions that seriously could kill other people and undermining what is a collective social effort to try to control this disease and get back to normal as soon as possible. Do you have anything to add on that, Howie?

Howie Lempel: I guess maybe one other thing I would add as far as those types of things that people can do or another reason why you really want to avoid transmitting a cold is you might be pretty sure that you don’t have COVID. Maybe you’ve matched up the symptoms and decided that it’s very unlikely. If you then you use that and then start going out, one big risk is that you get someone else a cold and then that cold, that person is going to spend the next two weeks wondering if they have this much more serious disease. They’re potentially going to spend those two weeks isolating themselves so that they know for sure they won’t spread it to anyone. And so just even if nobody gets sent to the hospital, the costs of getting someone else any kind of disease have just gone way up.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I might just add a little bit onto that about people who shouldn’t follow those instructions. I mean many listeners will be working in hospitals or they will be helping deliver electricity or collecting the trash or making the water function or delivering medicine to people in hospitals or just delivering groceries and essential items to people. Obviously those people, it’s impossible for them to stay at home. They’re the heroes who are keeping society functioning through this time. And hopefully they are getting instructions from their employer on how to minimize the risk to them and others of them transmitting the disease. I suppose obviously just trying to stay away from people and in some high risk professions, potentially wearing masks. But I guess we’ll leave that to people’s employers to offer advice on.

Robert Wiblin: Let’s just talk quickly about how you can try to get some idea of whether you have COVID or some other condition. I suppose in your case, Howie, you’re deciding to basically play it safe and regardless, to isolate yourself as much as possible. But we do have some ideas. Like if you think you have a 50% chance of having COVID on base rates, then you can look at your symptoms and potentially shift that estimate up a little bit up and down. Do you want to explain that?

Howie Lempel: Yeah, sure. So two of the symptoms that seem to be most common are dry cough and fever. And so that might be about when you start taking the possibility seriously that that’s what you’ve got. And there are some other symptoms that seem to be fairly uncommon in COVID relative to other similar diseases. Only 5% of people admitted to a hospital with COVID had a sore throat. Only 4% had a runny nose. 2% had diarrhea. So if all you’ve got is a sore throat and a runny nose, that’s a pretty good sign that you probably have something else.

Howie Lempel: If you’ve got a fever and a cough and a runny nose, you should certainly be taking the possibility that’s COVID quite seriously. But those are also pretty common symptoms. The runny nose makes it a bit more likely that maybe it’s something like flu where runny noses might be more common. And so that’s sort of the way that I would be thinking about figuring out how likely you are to be sick. But that said, I think being just on the cautious side, because it’s bad to spread any type of illness right now seems really important. And then the findings that we have on symptoms come from a study of a hundred hospitalized patients, so it wouldn’t be shocking to me if we had fairly different beliefs sometime down the road.

Robert Wiblin: Interestingly, I started getting cold symptoms a bit over three weeks ago. At the time, I estimated that there was kind of, given the number of people who start getting a cold or flu symptoms just every day regardless of COVID and given the number of people who we thought were infected in the UK, I think there was a base rate of about one in 3000 that had COVID. And then also, my symptoms weren’t ever a good match. So I had a runny nose and no fever. So that made it seem less likely. Then just a week ago I started getting cold symptoms again. By that stage, it seemed like the base rate had probably climbed potentially as high as one in a hundred. Fortunately, again, my symptoms didn’t match at all, so I don’t think that I actually have been infected.

Robert Wiblin: Fortunately, I’m also isolated out here and isolating myself. So fingers crossed, not passing it to anyone regardless of whether it is or isn’t. But it is interesting just how quickly this disease has spread such that a few weeks ago, the odds of you having it, if you had these symptoms was very low. But it is ramping up incredibly quickly.

What governments should do (Rob’s guess) [00:41:03]

Robert Wiblin: All right, let’s maybe talk about the situation in different countries. I actually spend a lot of my days at the moment looking over the case confirmation numbers, the testing numbers, the death numbers for different countries to understand which ones have the worst situation and which ones… well, the thing that I’m most interested in is finding out which countries are managing to successfully contain and suppress the infection and potentially turn things around.

Robert Wiblin: So as I mentioned, I guess things are very bad in Italy and Spain where they now have almost a full lockdown and people are not allowed to leave their houses unless they have a central business. Those countries seem to now have less than exponential growth, which is perhaps what you would expect if you were seeing a decrease in the number of contacts of people, starting a week or two ago, when people would have been exposed to the virus if they were now starting to get symptoms and get tested.

Robert Wiblin: Things are bad in France, Germany and Switzerland. They’re somewhat less bad in the UK, Australia and Canada. But they’re only days or a week behind. There’s other countries that are in a much worse situation. There’s only very limited breathing space for them to try to change things so that they don’t end up in the same situation that France, Italy, Spain, Switzerland are in now.

Robert Wiblin: It’s basically I think unknown what the situation is in the US because the testing has been so weak and as we mentioned, the testing in many poorer countries, many developing countries is basically completely absent so we just don’t have a clear picture at all. Is there anything you want to add on that, Howie?

Howie Lempel: No, that seems like a good summary to me.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. Okay. And then the countries that are doing well. We have China, as we mentioned, which basically has suppressed the illness. South Korea, through massive testing, seems to have brought down the number of new cases below 100 each day and held it there. Singapore has a lot of testing and it also seems to have kept the number of new cases each day to about 10 or 20. There’s also Hong Kong, which actually I haven’t looked at that data in the last few days, so I’m not quite as familiar.

Robert Wiblin: A lot of people mentioned Japan. I was a bit disappointed to look yesterday and see that they actually had not been testing many people. So I suspect that the disease may be quite a bit more widespread in Japan than is appreciated and perhaps it’s a bit of a statistical illusion that they’re suppressing it as much as it seems. They had a 5% confirmation rate from memory, but they were like relative to the population of Japan; the number of tests was really quite low. Lower than in other places. So that’s a little bit concerning.

Robert Wiblin: Taiwan has done well despite the fact that they are incredibly linked with China. They had a very early response: manufacturing masks, discouraging people from going out, doing widespread testing, doing widespread contact tracing, preventing people from entering the country if they had, in the last 14 days, been in any region where COVID was prevalent. And so they have managed to bring down new cases to a fairly low and constant rate, and fingers crossed they’ll be able to keep it there.

Robert Wiblin: Someone was telling me that Kuwait has done a good job, but I haven’t had a chance to look at that yet. So that’s something that I’ll hopefully get to later in the day. Are there any other good news stories that you’d like to mention, Howie?

Howie Lempel: I think you’ve gotten most of the ones that I know of.

Robert Wiblin: Right. So I think what we can learn from this is that if you do the right combination of policies and you’re willing to pay the cost and to take action soon enough and you’re organized enough, this disease is controllable. I think there’s pretty good evidence of that now, at least for societies that can potentially do the kinds of things that China, South Korea, Singapore or Taiwan are doing, which I guess not every country can do, but I’m optimistic that places like the UK, Canada and Australia could do if they had the will and they started doing it as quickly as possible now.

Howie Lempel: That seems right as a proof of concept, but it’s still too early to see how. Both, I haven’t seen any great measures of costliness to compare it to and it’s still too early to see what happens as you roll it back. It’s definitely a huge win if all you had to do was tough it out for a couple of months. But that becomes a harder call as you go from there.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. There’s a few ways that this could end up being mistaken I suppose. Yeah, as you mentioned, it could be that any loosening up of these restrictions means that you just get outbreaks again and so you’re kind of stuck in this constant bind where you have to keep imposing a high cost on people. Interestingly, in China and Singapore and Taiwan, they don’t have a lockdown. They don’t have lockdown conditions in South Korea. People are able to move around and life is continuing to a decent degree as normal. That is giving me some hope. I guess it’s possible that despite the fact that they’re doing quite a lot of testing, they’re still missing a lot of cases and it’s spreading under the radar and so it could be an illusion that that case numbers are as low as they are.

Robert Wiblin: What other ways could this… I suppose it could also just be the case that these countries are exceptionally more organized than other places and so other areas won’t be able to copy them. And then potentially, I suppose, somewhere like Singapore could just end up being overwhelmed by travelers from other countries bringing it in and that could exceed their capacity at containment and suppression and so they could end up failing in the long term. Is there any other ways that that lesson could end up being wrong?

Howie Lempel: Those seem like the main risks to me.

Robert Wiblin: It might just be worth me listing off again the things that I’m aware that these successful countries have done, especially the ones that were able to control cases without having a full lockdown. This is something that I’m researching a lot at the moment, trying to figure out, what is the pattern of what successful countries have been doing. So we might have more to say about this in a future episode or at least maybe in an article on our website.

Robert Wiblin: But basically South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, they ramped up their testing capability very early and very aggressively. They developed places that people could go and get tested that were unlikely to then infect other people in the process of them getting there and waiting for the test results and so on. So they were able to test a lot of people from an early stage. They then had mandated home isolation for people who had tested positive or they kept them in hospitals. And they really did enforce that and would actually fine people and punish people if they violated those rules.

Robert Wiblin: In at least some of those countries, they also would chase up people who had had exposure to people who tested positive and then similarly, on pain of a serious fine or a criminal conviction, require them to remain in their rooms where they wouldn’t infect other people.

Robert Wiblin: Many of these places also increased… they stockpiled more masks than other places did and they have ramped up their production of face masks quite aggressively. I know there’s some skepticism among some people about the value of face masks, but there is an interesting pattern that countries that use face masks do seem to be doing better than countries that don’t. That could just be correlation or coincidence, but many of these countries do seem to think that people wearing face masks is an important aspect of their control strategy.

Robert Wiblin: Many of them imposed stronger restrictions on travel into their countries from regions where there were active cases of COVID demonstrated from an earlier date. For example, Taiwan started scanning people who were coming from Wuhan as early as the 31st of December for any cold symptoms, which is well ahead of what other countries, certainly what the UK or U.S. were doing. But that’s not surprising given how well connected they were with China.

Robert Wiblin: But they also cut off any connections from Wuhan and the rest of China quite a bit earlier than other countries did. They also actively were tracking down people’s travel history so they were able to find out whether people had been in those regions within the last two weeks and then deny them entry on that basis, whereas other countries have mostly lacked that capability.

Robert Wiblin: In many places they have also been able to use people’s phone records to see what phone numbers have had GPS tracking close to their phone, and then notify them immediately that they are required to stay home and self isolate. Which you can imagine there’s a risk that those people have been infected and then they immediately find out that someone they’ve met has had a positive case and then they go home and self isolate. That does make it a bunch harder for the virus to spread because you’re just, without having to keep everyone at home, you’re identifying most of the people who are most likely to have received the virus. Is there anything else you want to add on that, Howie?

Howie Lempel: Yeah. So one question is, do you have a sense of how many of those countries are countries that have had recent experience with just really serious respiratory illnesses, whether it’s sort of SARS or whether it’s MERS?

Robert Wiblin: Yes, all of them. Which may explain why they had all this infrastructure ready to go. And I guess that does suggest that it could be harder for other countries to copy. So Taiwan and Singapore both had SARS outbreaks and built institutions and processes in order to prevent a repeat of that including these kinds of tracking mechanisms. And I guess that could have been what prompted them to stockpile more materials for the situation.

Robert Wiblin: And South Korea had an outbreak of MERS, although I don’t know the details about that, which I think caused them to ramp up their testing capabilities. I’m trying to think are there any others? I guess Hong Kong was affected by SARS, similarly. China obviously was massively affected by SARS, which I guess in retrospect might have been a fortunate test run that has allowed them to do what they’re doing now.

Howie Lempel: And then I guess one other question that I’m very confused about when I think about comparisons across countries is why the U.S. and the UK seem to have been so unable to copy the parts of those strategies that seem most uncontroversial. Especially with rolling out testing. I mean as far as I’ve read, we basically have South Korea just way ahead of the United States having like seemingly unlimited drive-through testing while the U.S. is barely able to test anyone and still trying to manufacture its own tests. And I’m wondering if you have any insight into, I guess, both. What’s preventing the U.S. from moving more quickly and then also why is it not the case that as soon as this happens, the U.S. just buys IP from South Korea and just starts making the same tests?

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I don’t understand the details of that. There does seem to be quite a big difference between the UK and Australia and the U.S. The U.S. seems to be doing exceptionally poorly in this regard. The number who were tested in the UK, I wish it were higher, but it’s at least a decent number. I think 20,000, 30,000 by now, which could be worse. Australia has actually tested 80,000 people when I last checked, which is actually quite a lot.

Robert Wiblin: The U.S., so I’m aware of part of the problem which was that the CDC said that they wanted to do all of the testing themselves and then they, I think, bought a bunch of tests and then they found out they didn’t work and then they tried to make their own and that didn’t work and they weren’t approving anyone else to conduct tests. And unfortunately, bizarrely during a pandemic, they have the ability to deny anyone else the ability to do tests for the disease.

Howie Lempel: My impression is that it was the FDA.

Robert Wiblin: Oh sorry, yeah. Sorry, I’m thinking of the government as a whole. But yeah, the FDA was blocking anyone else from rolling out their tests. And I think that has only recently kind of been relaxed, that they’ve started approving things. I mean, it’s one thing I understand… It’s to hard to run these projects, to scale these things up massively. It’s possible that any one institution might make mistakes and so they don’t manage to scale it up. But to forcibly, through your own regulatory power, prevent other hospitals, other research groups that can actually test people, that might save many lives and save trillions of dollars of lost GDP by controlling this thing. To use the law to prevent them from doing it just seems like an absolute barbarity to me. Made me furious and I think there’ll be a commission that will… hopefully heads will roll for this appalling decision.

Howie Lempel: My initial instinct is similar to yours, although I would really like to see any information at all about how accurate the other tests are. Maybe see where someone’s coming from. If you find out that the tests in South Korea actually don’t look so hot. But I suspect we’ll find out that they’re actually more than sufficient.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, I mean it seems like they should be able to develop them and then roll them out and then in an emergency situation, then test later. Are they working once they’d actually started applying it, rather than having this very command and control centralized mechanism, which has this one single point of failure, the CDC, that then basically just can’t test people almost at all for weeks. Shocking.

Robert Wiblin: So much time wasted. Especially, it seems like different labs in different manufacturing centers around the world have had different approaches to producing these tests and it’s impossible for anyone to know ahead of time which one of these is going to have the best trade-off between cost and ability to manufacture them quickly and reliability.

Robert Wiblin: So they could really want lots of different groups to be trying to make these things. And then just whoever can make the most of them, start buying tons of it. But that was not the way the U.S. was thinking about it. Because I think a single university research lab in Washington, from memory, who managed to test more people than the entire federal government. There’s a single billionaire in China who sent more tests to the U.S. than the entire federal government has managed to provide up to now by a large fraction. So it gives you some sense of the scale of the failure. At least if their reporting on this is at all correct.

Howie Lempel: Yep, that’s right.

Robert Wiblin: Yeah. I expect that in terms of why other countries haven’t been able to do more, probably it is just a slightly difficult technical challenge to make these tests good and then manufacture very large numbers of them. I suppose if you have not done any of the preparatory work to figure out how you would do that. But I don’t know the details of… I don’t know the science behind it.

Robert Wiblin: I guess we talked about some ways that countries that we’re in, countries that many listeners are in, like the UK, U.S. and Australia, why they might not be able to copy. But I am somewhat optimistic that China, which has some very strong aspects of state capacity, but also some areas in which it’s weaker, did manage to successfully contain the disease, starting from what was really quite a high density of cases in Wuhan. Potentially like a large fraction of the population has already been infected. So it does seem worth it. Trying to give it a go to do that rather than just allow 1% of the population to die.

Robert Wiblin: And if we have a strong response now, then we can always decide later that it’s not practical and give up on that. Or we could learn from the experience of other countries that it doesn’t work in the long term. But if we don’t act very decisively and very quickly, then the door for that will close and we will just have to accept the very high level of fatality. And, of course, an enormous economic effect as well. If so many people are getting sick, if so many people are dying, I don’t think that is going to be great for consumer confidence. Of course, having to stay at home isn’t great either, but also just allowing very large numbers of fatalities will bring its own massive economic repercussions as well.

Robert Wiblin: I’ll just add that we’re talking about case studies in all these different countries: Italy, South Korea and so on. There’s a Wikipedia entry on the 2020 coronavirus pandemic in X for basically every country that is affected. Potentially just every country in the world by this point. Where you can often see a timeline of their response and you can see these nice graphs that show the increase in tests and confirmations and deaths and so on. So you can potentially learn about this yourself. There’s nothing magical that we’re doing here. Basically just requires the legwork of reading these things and trying to understand what’s happening in each country.

Howie Lempel: I guess in the story where you’re able to have a really short suppression period and then able to open up again afterwards and sort of from there, catch cases as they come up. That sounds like a pretty good story to me. I guess I worry about, one worry I have is just the other possibilities. At least some governments seem to be talking like we are going to have these intense measures and we’re trying to wait out a vaccine. And I guess I don’t feel like I’ve seen a lot of folks really look hard at how much of a talk to the economy are we really talking about here.

Howie Lempel: And who is this affecting? How are they going to make it through? And just really looking at that impact and asking, “Is it worth it to essentially shut down the economy for 12 to 18 months?” So I don’t know. Do you have any thoughts on, if the likelihood that that ends up being what the intervention looks like? And does it still look worthwhile if that’s what it looks like?

Robert Wiblin: Yeah, obviously I haven’t done all the modeling and the cost-benefit analysis there. I guess I’m not sure that anyone in the world has done that super well. I guess the Imperial College London study that we’ll link to might come closest, but that was obviously very rushed out the door, and there’s a lot more than one can say about it. It might be worth, at this point, me mapping out my view of what will happen over a longer period of time, so we can perhaps get an intuitive sense of how costly it will be if I’m right.

Robert Wiblin: So I think first, countries like the UK or US, where there’s already widespread community transmission, quite a lot of people have it. They’re going to have to enter a suppress phase, which could last, I guess, two to five weeks, which will be very costly. But the goal there is to bring the transition rate from one person to another well below one. So then over time, the number of new cases just starts coming down potentially quite a lot. More or less you have to do that, because otherwise if you don’t, within a few weeks, your country is already going to be overrun with cases. Then we can do the phase that China is in now, which I guess I’m going to call the release phase, which will happen potentially over one to six months, depending on how long it takes for us to learn how much we can get back to normal life.

Robert Wiblin: So obviously, during the suppress phase, we still have to keep supermarkets running. We still have to keep pharmacies running. We still have to keep the electricity grid running. But, during the release phase, we’ll figure out how much can we add back? How many people can go back to their offices? Can gyms reopen? Can people start going out on the street again? Without, the R nought figure, that is, the number of people who catch it from each affected person rising above one. If we can keep the R nought below one, then we’re in a stable situation, and we can just keep going with a relatively small manageable number of cases until we have a more serious solution to the problem.

Robert Wiblin: And it’s going to have to involve a bunch of learning on our part. How can we still have people having contact with one another without having lots of transmission? And fortunately, one advantage that we have is that we are going to be able to learn from the experience of other countries that are several months ahead of us. Countries like China, where they have been trying to figure out, how can they restart the economy, or how can they get things somewhat back to normal without lots of transmission. So things like just checking people’s temperature everywhere that you can so that as soon as people start showing a fever, they can self-isolate and potentially go to a special clinic where they can get tested quickly before they pass it on to other people.

Robert Wiblin: We’re already messaging a lot on hand washing. We’re going to have to keep that up a great deal just to have very high levels of personal hygiene and sanitation. These things like offices should be very well ventilated because that helps to clear out the air that might have these aerosolized virus particles in it. I guess, I don’t know how significant each of these individual things is, but probably together, they’re going to add up a fair bit.

Robert Wiblin: And also just massively stigmatizing people coughing in an uncovered way. It’s already a little bit rude in normal times. I think, at this point in history, it should be viewed as just a deadly thing to be doing in public. And so the hope is by adding those kinds of things, and then other things that we’ll learn from countries like Taiwan and China, we’ll be able to potentially have many, especially younger people, especially a bit healthier people who are less likely to get infected and also less likely to be killed by the virus, to go back to normal life. That’s one to six months period, I’m guessing.

Robert Wiblin: Then we enter this longer muddle through period, where I expect that having done as much as we can to get things back to normal, we’re going to sometimes have outbreaks in particular locations in cities, where it turns out that we’ve allowed R nought to slip above one and more people to start transmitting the virus and more people to catch it.

Robert Wiblin: And so we’re going to end up having to do this difficult balancing act between preventing outbreaks and having the economy function and not having a massive depression. But fortunately, over this time, we’ll likely have ramped up relevant medical training. We’ll have built lots of ventilators. We’ll potentially by this stage have quite effective treatments in terms of antivirals that, fingers crossed, we’ll be able to have manufactured a lot of. Hopefully the testing capability issues that we’ve had over the last month or two we’ll have resolved by then. And we’ll be able to have test far more people, and get the results much more quickly.

Robert Wiblin: And so that will potentially all make it easier to control outbreaks where they occur in particular locations. We might even have, in countries like the UK, figured out this mechanism for texting everyone who’s had exposure to someone who ends up getting diagnosed. That sounds like a technically complicated thing to do, but six months maybe if we really focus on it, we can do it.

Robert Wiblin: And through all of this time, we’re going to have researchers working incredibly hard, many labs converting over to working on a coronavirus vaccine, to working on testing antivirals to figure out which existing antivirals are most effective. And that, fingers crossed, will last only six to 18 months before we either get a vaccine, or very effective antivirals that do effectively mean the disease is rarely deadly, or potentially we now have so many ventilators and we’ve scaled up other treatments so well that we can relax and allow many people to become infected without freaking out too much.

Robert Wiblin: So that gives you some idea of the scale of the effort that we’re talking about here. And I don’t know whether that is more of an economic cost than most people expect it or less. We’re in for a pretty rough economic ride regardless, as I was saying earlier, and my hope is that this is the least damage approach.

Howie Lempel: How likely do you think it is that during the release phase we’re going to see something that makes us decide that this plan just isn’t that viable?

Robert Wiblin: Well, we might have a decent idea before we even get there because we’ll find out whether South Korea has been able to maintain control for more than a month. I guess maybe one in three. I guess I’m somewhat optimistic that if we keep a third of people who most don’t need to go back to work at home, and other people are doing everything they can, hopefully, out of fear of their own lives, quite literally, to avoid catching this virus, that we will be able to keep R nought at a sufficiently low level. Perhaps I’m just naively optimistic, but I guess I don’t feel like I’ve been naively optimistic about most other things so far.

Howie Lempel: That seems absolutely true.

Robert Wiblin: Do you have a more pessimistic take?

Howie Lempel: I guess I think that there is a world in which countries like the US, and the UK, and Australia are able to maintain very low levels of virus for a long time. I think I’m probably a bit more worried than you that it requires staying in a situation that’s similar to the suppress phase for a fairly long time, but I’m pretty unclear on whether or not we’re going to be able to start opening things up, and not have it just shoot up to another outbreak again. And countries have shown the ability to do it. I mean, if you lower the cases enough, then you’re able to just track every contact of anyone who does have it, and you are able to really cut down outbreaks that way. But whether or not these countries in particular can do it successfully, I think I’m a bit more worried.

Robert Wiblin: Okay. Interesting. So I guess a few responses to that. One is that even if we do end up abandoning this long term strategy, doing the suppress thing now and then trying to flatten the curve does still save quite a lot of lives, because in the meantime, we can potentially have manufactured some more antivirals, and some more ventilators, and have more ability to treat people without other people catching it.