#140 – Bear Braumoeller on the case that war isn't in decline

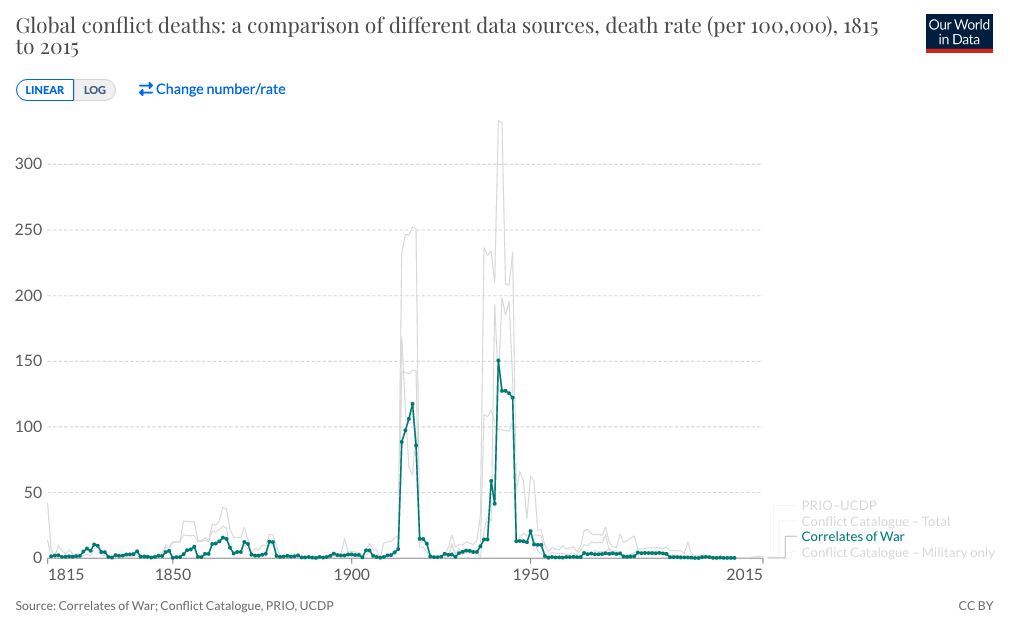

Is war in long-term decline? Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature brought this previously obscure academic question to the centre of public debate, and pointed to rates of death in war to argue energetically that war is on the way out.

But that idea divides war scholars and statisticians, and so Better Angels has prompted a spirited debate, with datasets and statistical analyses exchanged back and forth year after year. The lack of consensus has left a somewhat bewildered public (including host Rob Wiblin) unsure quite what to believe.

Today’s guest, professor in political science Bear Braumoeller, is one of the scholars who believes we lack convincing evidence that warlikeness is in long-term decline. He collected the analysis that led him to that conclusion in his 2019 book, Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age.

The question is of great practical importance. The US and PRC are entering a period of renewed great power competition, with Taiwan as a potential trigger for war, and Russia is once more invading and attempting to annex the territory of its neighbours.

If war has been going out of fashion since the start of the Enlightenment, we might console ourselves that however nerve-wracking these present circumstances may feel, modern culture will throw up powerful barriers to another world war. But if we’re as war-prone as we ever have been, one need only inspect the record of the 20th century to recoil in horror at what might await us in the 21st.

Bear argues that the second reaction is the appropriate one. The world has gone up in flames many times through history, with roughly 0.5% of the population dying in the Napoleonic Wars, 1% in World War I, 3% in World War II, and perhaps 10% during the Mongol conquests. And with no reason to think similar catastrophes are any less likely today, complacency could lead us to sleepwalk into disaster.

He gets to this conclusion primarily by analysing the datasets of the decades-old Correlates of War project, which aspires to track all interstate conflicts and battlefield deaths since 1815. In Only the Dead, he chops up and inspects this data dozens of different ways, to test if there are any shifts over time which seem larger than what could be explained by chance variation alone.

Among other metrics, Bear looks at:

- Battlefield deaths alone, as a percentage of combatants’ populations, and as a percentage of world population.

- The total number of wars starting in a given year.

- Rates of war initiation as a fraction of all country pairs capable of fighting wars.

- How likely it was during different periods that a given war would double in size.

In a nutshell, and taking in the full picture painted by these different measures, Bear simply finds no general trend in either direction from 1815 through today. It seems like, as philosopher George Santayana lamented in 1922, “only the dead have seen the end of war”.

That’s not to say things are the same in all periods. Depending on which indication of warlikeness you give the greatest weight, you can point to some periods that seem violent or pacific beyond what might be explained by random variation.

For instance, Bear points out that war initiation really did go down a lot at the end of the Cold War, with peace probably fostered by a period of unipolar US dominance, and the end of great power funding for proxy wars.

But that drop came after a period of somewhat above-average warlikeness during the Cold War. And surprisingly, the most peaceful period in Europe turns out not to be 1990–2015, but rather 1815–1855, during which the monarchical ‘Concert of Europe,’ scarred by the Napoleonic Wars, worked together to prevent revolution and interstate aggression.

Why haven’t modern ideas about the immorality of violence led to the decline of war, when it’s such a natural thing to expect? Bear is no Enlightenment scholar, but his book notes (among other reasons) that while modernity threw up new reasons to embrace pacifism, it also gave us new reasons to embrace violence: as a means to overthrow monarchy, distribute the means of production more equally, or protect people a continent away from ethnic cleansing — all motives that would have been foreign in the 15th century.

In today’s conversation, Bear and Rob discuss all of the above in more detail than even a usual 80,000 Hours podcast episode, as well as:

- What would Bear’s critics say in response to all this?

- What do the optimists get right?

- What are the biggest problems with the Correlates of War dataset?

- How does one do proper statistical tests for events that are clumped together, like war deaths?

- Why are deaths in war so concentrated in a handful of the most extreme events?

- Did the ideas of the Enlightenment promote nonviolence, on balance?

- Were early states more or less violent than groups of hunter-gatherers?

- If Bear is right, what can be done?

- How did the ‘Concert of Europe’ or ‘Bismarckian system’ maintain peace in the 19th century?

- Which wars are remarkable but largely unknown?

- What’s the connection between individual attitudes and group behaviour?

- Is it a problem that this dataset looks at just the ‘state system’ and ‘battlefield deaths’?

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type ‘80,000 Hours’ into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

Producer: Keiran Harris

Audio mastering: Ryan Kessler

Transcriptions: Katy Moore