Can you have more impact working in a foundation than earning to give?

Photo credit: Flickr – Refracted Moments

Key points

- Working to improve grants at a foundation could well be more effective in terms of the impact of the money moved than earning to give. Which is better will usually come down to how good your personal opportunities are to make money, or get a job at a large foundation working on an important cause.

- If you know of a cause area or organisation that is many times more effective than what any foundations you could work at would make grants to, then earning to give is likely to be better.

- There are other issues, like the impact on your long-term career trajectory, that you have to consider as well as the direct impact of the money you move.

As soon as we thought of the idea of earning to give, we started thinking of ways to beat it. One idea that was floated in the very early days of 80,000 Hours was working in a foundation to allocate grants to more effective causes and organisations. Since a foundations grantmaker might allocate tens of millions of funding, far more than they could earn, maybe they could have a greater impact this way?

In this post, we provide a model for comparing the impact of foundations grantmaking and earning to give, which some people may find useful for specific scenarios where they have more info on the inputs. We also provide some very tentative estimates using the model to demonstrate how it works. Our highly tentative conclusion from using the model is that foundations grantmaking is higher impact than earning to give if you’re grantmaking in a high-potential cause.

A big disclaimer is that this is a very rough comparison which we are highly uncertain about. We make a simple model to compare foundations grant-making with earning to give, which is subject to both model and parameter uncertainty, and we caution against taking the results of comparisons like these literally. We should also make it clear that we are not making an ‘all things considered’ comparison of working at a foundation with earning to give – that depends on many other factors. See our profile on foundations for an overall picture.

How to compare the impact of foundations grantmaking with earning to give

Estimating the impact that foundation grantmakers have

A simple way to model the impact from grant allocations is as the amount of money you give out in grants multiplied by the (average) cost-effectiveness of where those grants go, and then subtract the amount in grants that would have been allocated if you didn’t take the job multiplied by the cost-effectiveness of where those grants would have gone:

Foundation Impact = (Money given in grants * Cost-effectiveness) - (Counterfactual money given in grants * Counterfactual cost-effectiveness)

If we assume that the money given out won’t differ much between foundation grantmakers, we can simplify the model by taking out the money given out in grants as a common factor:

Foundation Impact = Money given in grants * (Cost-effectiveness - Counterfactual cost-effectiveness)

Let’s call the difference between the cost-effectiveness of where you allocate grants and the cost-effectiveness of where the grants would have gone otherwise the ‘cost-effectiveness boost’:

Cost-effectiveness boost = (Cost-effectiveness - Counterfactual cost-effectiveness)

So the more you manage to improve the cost-effectiveness of grants, and the more grant money you manage to apply that improvement to, the greater your impact at a foundation.

Estimating the impact from earning to give donations

The impact from donations in earning to give can be modelled as the amount of money you donate multiplied by the (average) cost-effectiveness of where you donate:1

Earning to give impact = Money donated * Cost-effectiveness

If we combine these two models, the impact from allocating grants in a foundation will match the impact of earning to give donations when:

Money given in grants * (Cost-effectiveness - Counterfactual cost-effectiveness) = Money donated * Cost-effectiveness

Or expressed slightly differently:

Money given in grants * Cost-effectiveness boost = Money donated * Cost-effectiveness

Estimating the variables

Kerry Vaughan, who was a grantmaker at the Arnold Foundation, estimates that at major foundations program officers oversee budgets of around $10 million per year, and at smaller foundations like the Arnold Foundation around $4.5 million. For the amount of money donated in earning to give, we think that talented graduates who seek high-earning positions can donate in the range of $30,000 – $200,000 per year. We invite you to put in your own estimates for earnings into our model.

Assuming that you donate $100,000 in earning to give, and that you allocate $10 million as a foundation grantmaker, then our model looks as follows:

$10,000,000 * (Cost-effectiveness of grants - Counterfactual cost-effectiveness) = $100,000 * Cost-effectiveness of donations

Or expressed slightly differently:

$10,000,000 * Cost-effectiveness boost = $100,000 * Cost-effectiveness

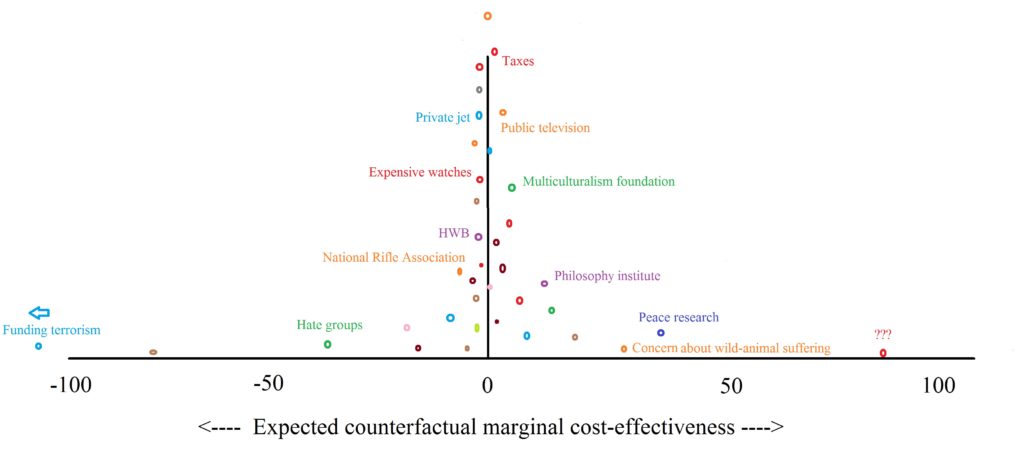

The most difficult variables to estimate are those concerning cost-effectiveness. Brian Tomasik estimates that “many charities differ by at most ~10 to ~100 times, and within a given field, the multipliers are probably less than a factor of ~5.” Assuming this is true (though many people think larger differences exist), the degree to which you can improve the effectiveness of grant allocations is at most ~10 to ~100 times, and because most foundation grantmakers are limited to a single cause, the improvement is at most ~5 times. It also suggests a difference of at most ~10 to ~100 times between the cost-effectiveness of organisations you donate money to in earning to give and the cause to which a foundation gives grants to.

Further reasons for expecting it to be hard to find opportunities that are vastly more cost-effective are in the following GiveWell blogposts:

- Broad Market Efficiency

- Trying (and failing) to find more funding gaps for delivering proven cost-effective interventions

- Why we should expect good giving to be hard

Our guess is that your cost-effectiveness boost as a foundation grantmaker is likely to be less than ~5 times, because:

- Most grant-makers are constrained by cause (e.g. Global Health) and intervention (e.g. malaria nets) that they can give out grants to. They also usually have to get approval from the board of the foundation for the organisations they want to allocate grants to.2 The smaller the range of options open to grant-makers, the smaller the difference in effectiveness between giving opportunities is likely to be. For example, GiveWell estimates that AMF, one of its recommended charities, is only 9% more cost-effective than other malaria net organisations. Even AMF’s own estimate puts it only at 17% more cost-effective than other malaria net organisations.3 We can’t generalise much from this, but it is an example of an intervention with relatively little (estimated) room for improvement in cost-effectiveness.

- Even if you manage to move some grants to organisations that are ~5 times more effective than they would have been otherwise, this is an upper bound on the difference between the effectiveness of organisations, so your average cost-effectiveness boost is likely to be significantly lower than ~5 times.

- We expect other foundation grant-makers to be relatively skilled at allocating grants to effective opportunities, which decreases the chance that you’ll find opportunities that are significantly better.4

Overall, we are highly uncertain about the improvement in cost-effectiveness that you could make as a foundation grantmaker on average, but given the above, we think it’s likely to be significantly less than ~5 times and in the range of 1.01x – 1.5x (1%-50%).

When is foundations grantmaking better than earning to give?

If we assume that you donate $100,000 in earning to give, and that you allocate $10 million as a foundation grantmaker, then foundations match the impact of earning to give in the following in the following scenarios:

| Scenario | Cost-effectiveness of average grant in foundation (as percentage of cost-effectiveness of earning to give donations) | Increase in cost-effectiveness of grants over average grant needed to match earning to give impact |

|---|---|---|

| High potential cause | 25% | 4% |

| Medium potential cause | 10% | 10% |

| Low potential cause | 2% | 50% |

If the cause is high-potential, so the average grants within the cause are at least 25% as effective as where you’d personally donate, then you only need to increase the efficiency of granting by 4%, which seems achievable.

If the cause is low potential i.e. typical grants are only 2% as effective as where you’d donate, you need to improve effectiveness by at least 50%. We think a 50% is probably optimistic for what one staff member can achieve, so earning to give likely wins in this case.

For a medium-potential cause, it’s unclear.

A key consideration is clearly whether you think you know of giving opportunities that are significantly more effective than what any of the foundations you could work at would be willing to make grants to.

We invite you to put your own inputs into our model, and we want to stress again to treat the outputs of this model as highly tentative.

Notes and references

- We’ll assume that the the counterfactual cost-effectiveness of earning to give donations is small enough that we can ignore it.↩

- This is based on reading the formal job descriptions of various positions offered at foundations, conversations with some people working in the field, and the personal experience Kerry Vaughan working in a foundation for 3 years.↩

- “GiveWell calculates the cost per net for AMF at about $5.30. GiveWell has calculated the cost per net for other organisations as $5.80. At $5.30 per net, AMF is 9% more cost-effective than other organisations.”

“At $4.80 per net, [AMF’s calculated cost per net is] 17% more effective.”

- “In general, in interacting with major foundations (such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Hewlett Foundation,CIFF and Open Society Foundations), we’ve encountered many program officers whom we perceive as well-informed, genuinely altruistic, and relatively analytical in their approach. It’s difficult to evaluate the quality of these people’s work, but they certainly don’t fit the stereotype of the “story-oriented donor.”

“While I do believe we’ve found some places in which more money is needed to deliver more proven cost-effective interventions, doing so has been far more difficult than I expected.”