#56 – Persis Eskander on wild animal welfare and what, if anything, to do about it

Elephants in chains at travelling circuses; pregnant pigs trapped in coffin-sized crates at factory farms; deers living in the wild. We should welcome the last as a pleasant break from the horror, right?

Maybe, but maybe not. While we tend to have a romanticised view of nature, life in the wild includes a range of extremely negative experiences.

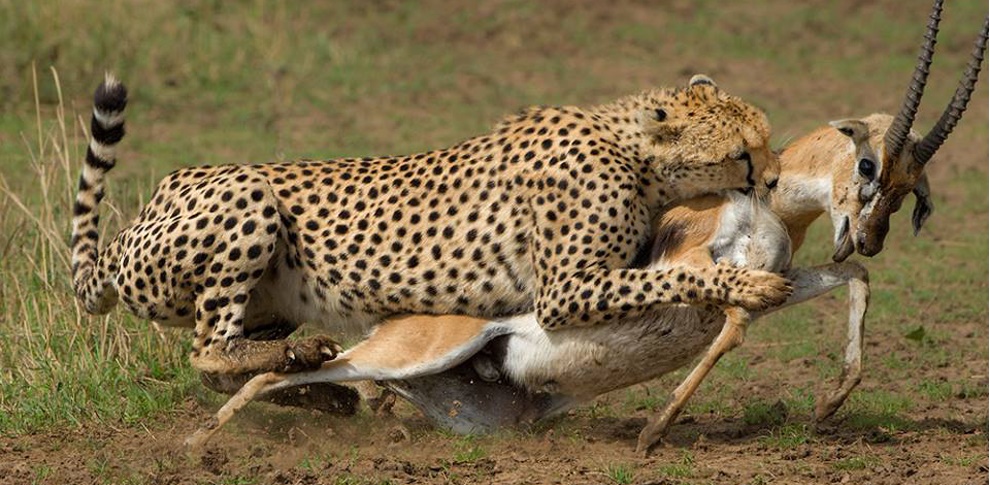

Most animals are hunted by predators, and constantly have to remain vigilant lest they be killed, and perhaps experience the terror of being eaten alive. Resource competition often leads to chronic hunger or starvation. Their diseases and injuries are never treated. In winter wild animals freeze to death and in droughts they die of heat or thirst.

There are fewer than 20 people in the world dedicating their lives to researching these problems.

But according to Persis Eskander, researcher at Open Philanthropy, if we sum up the negative experiences of all wild animals, their sheer number – trillions to quintillions, depending on which you count – could make the scale of the problem larger than most other near-term concerns.

Persis urges us to recognise that nature isn’t inherently good or bad, but rather the result of an amoral evolutionary process. For those that can’t survive the brutal indifference of their environment, life is often a series of bad experiences, followed by an even worse death.

But should we actually intervene? How do we know what animals are sentient? How often do animals really feel hunger, cold, fear, happiness, satisfaction, boredom, and intense agony? Are there long-term technologies that could some day allow us to massively improve wild animal welfare?

For most of these big questions, the answer is: we don’t know. And Persis thinks we’re far from knowing enough to start interfering with ecosystems. But that’s all the more reason to start considering these questions.

There are a few concrete steps we could take today, like improving the way wild caught fish are slaughtered. Fish might lack the charisma of a lion or the intelligence of a pig, but if they have the capacity to suffer — and evidence suggests that they do — we should be thinking of ways to kill them painlessly rather than allowing them to suffocate to death over hours.

In today’s interview we explore wild animal welfare as a new field of research, and discuss:

- Do we have a moral duty towards wild animals?

- How should we measure the number of wild animals?

- What are some key activities that generate a lot of suffering or pleasure for wild animals that people might not fully appreciate?

- Is there a danger in imagining how we as humans would feel if we were put into their situation?

- Should we eliminate parasites and predators?

- How important are insects?

- Interventions worth rolling out today

- How strongly should we focus on just avoiding humans going in and making things worse?

- How does this compare to work on farmed animal suffering?

- The most compelling arguments for not dedicating resources to wild animal welfare

- Is there much of a case for the idea that this work could improve the very long-term future of humanity?

- Would increasing concern for wild animals improve our values?

- How do you get academics to take an interest in this?

- How could autonomous drones improve wild animal welfare?

Rob is then joined by two of his colleagues — Niel Bowerman and Michelle Hutchinson — to quickly cover:

- The importance of figuring out your values

- Chemistry, psychology, and other different paths towards working on wild animal welfare

- How to break into new fields

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app. Or read the transcript below.

The 80,000 Hours Podcast is produced by Keiran Harris.