#33 – Anders Sandberg on what if we ended ageing, solar flares & the annual risk of nuclear war

Joseph Stalin had a life-extension program dedicated to making himself immortal. What if he had succeeded?

According to our last guest, Bryan Caplan, there’s an 80% chance that Stalin would still be ruling Russia today. Today’s guest disagrees.

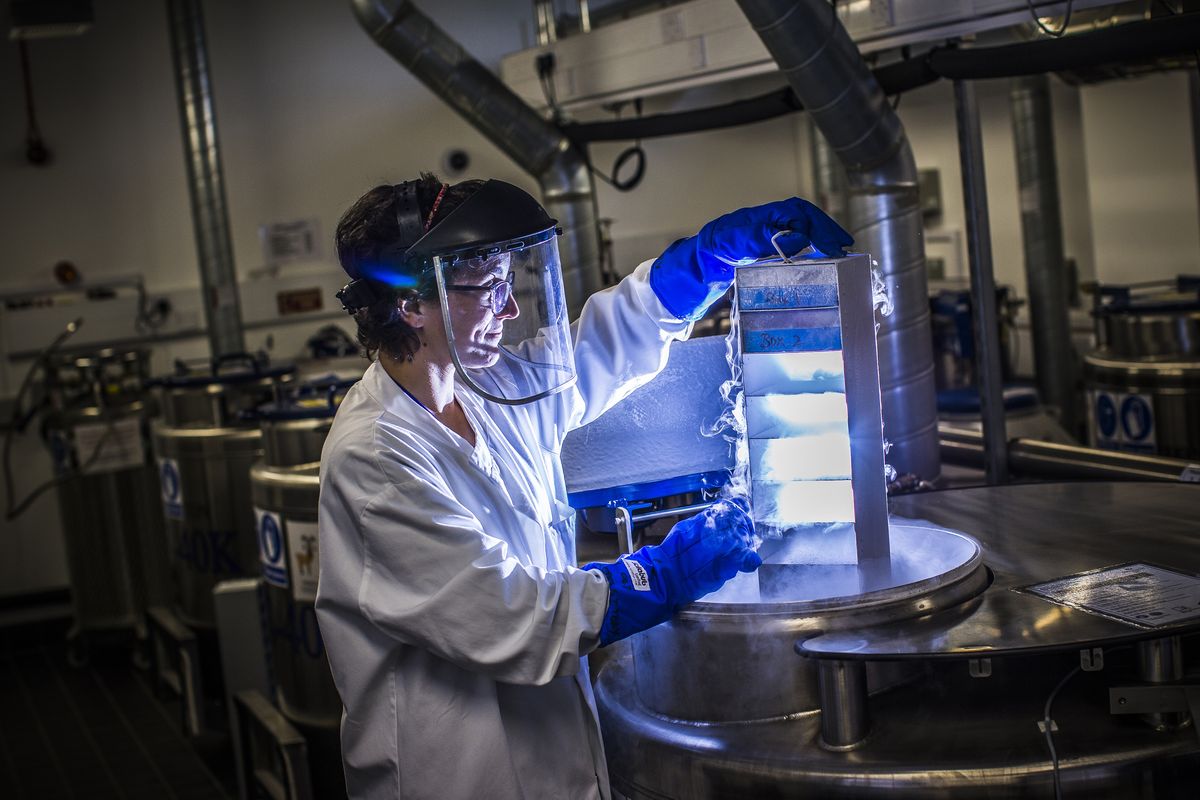

Like Stalin he has eyes for his own immortality – including an insurance plan that will cover the cost of cryogenically freezing himself after he dies – and thinks the technology to achieve it might be around the corner.

Fortunately for humanity though, that guest is probably one of the nicest people on the planet: Dr Anders Sandberg of Oxford University.

The potential availability of technology to delay or even stop ageing means this disagreement matters, so he has been trying to model what would really happen if both the very best and the very worst people in the world could live forever – among many other questions.

Anders, who studies low-probability high-stakes risks and the impact of technological change at the Future of Humanity Institute, is the first guest to appear twice on the 80,000 Hours Podcast and might just be the most interesting academic at Oxford.

His research interests include more or less everything, and bucking the academic trend towards intense specialization has earned him a devoted fan base.

Get this episode by subscribing to our podcast on the world’s most pressing problems and how to solve them: type 80,000 Hours into your podcasting app.

Last time we asked him why we don’t see aliens, and how to most efficiently colonise the universe. In today’s episode we ask about Anders’ other recent papers, including:

- Is it worth the money to freeze your body after death in the hope of future revival, like Anders has done?

- How much is our perception of the risk of nuclear war biased by the fact that we wouldn’t be alive to think about it had one happened?

- If biomedical research lets us slow down ageing would culture stagnate under the crushing weight of centenarians?

- What long-shot drugs can people take in their 70s to stave off death?

- Can science extend human (waking) life by cutting our need to sleep?

- How bad would it be if a solar flare took down the electricity grid? Could it happen?

- If you’re a scientist and you discover something exciting but dangerous, when should you keep it a secret and when should you share it?

- Will lifelike robots make us more inclined to dehumanise one another?

The 80,000 Hours Podcast is produced by Keiran Harris.