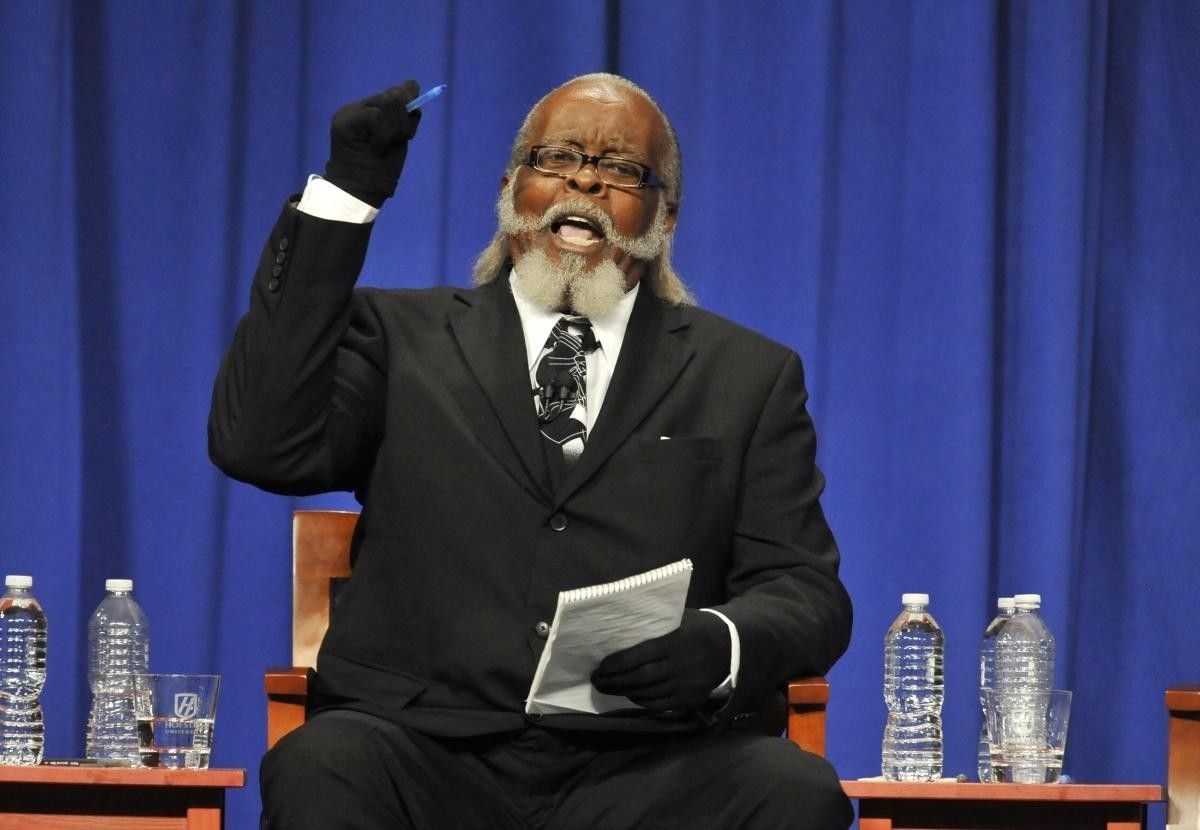

#2 – David Spiegelhalter on risk, statistics, and improving the public understanding of science

My colleague Jess Whittlestone and I spoke with Prof David Spiegelhalter, the Winton Professor of the Public Understanding of Risk at the University of Cambridge.

Prof Spiegelhalter tries to help people prioritise and respond to the many hazards we face, like getting cancer or dying in a car crash. To make the vagaries of life more intuitive he has had to invent concepts like the microlife, or a 30-minute change in life expectancy. He’s regularly in the UK media explaining the numbers that appear in the news, trying to assist both ordinary people and politicians to make sensible decisions based in the best evidence available.

We wanted to learn whether he thought a lifetime of work communicating science had actually had much impact on the world, and what advice he might have for people planning their careers today.

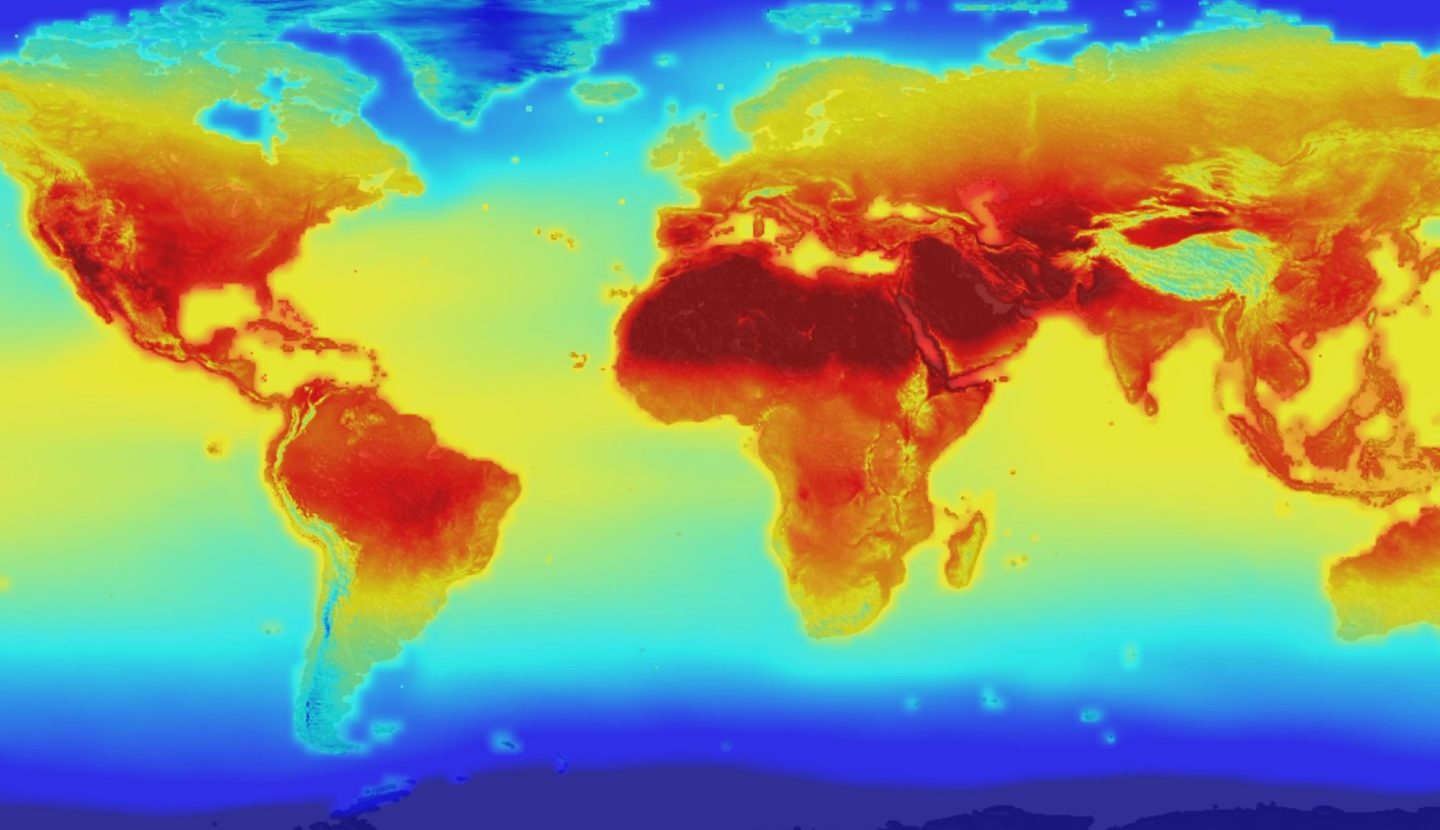

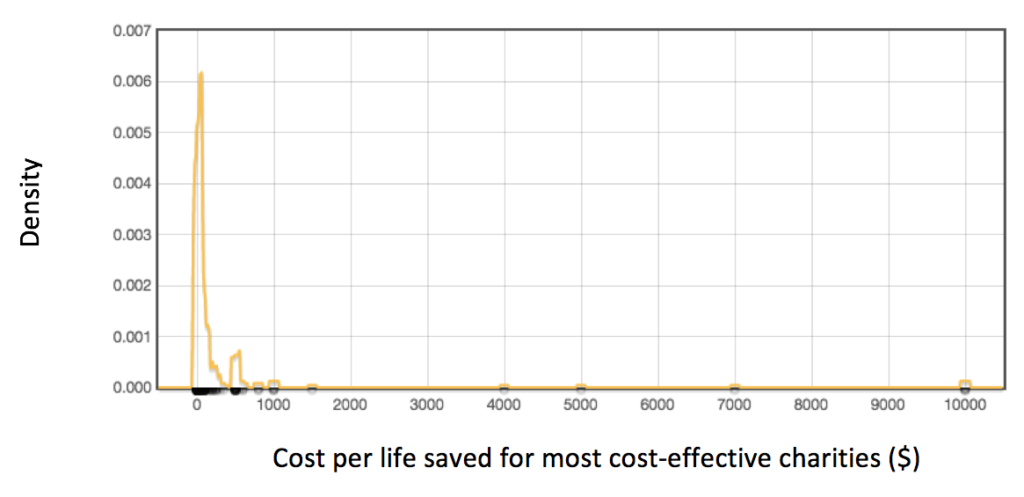

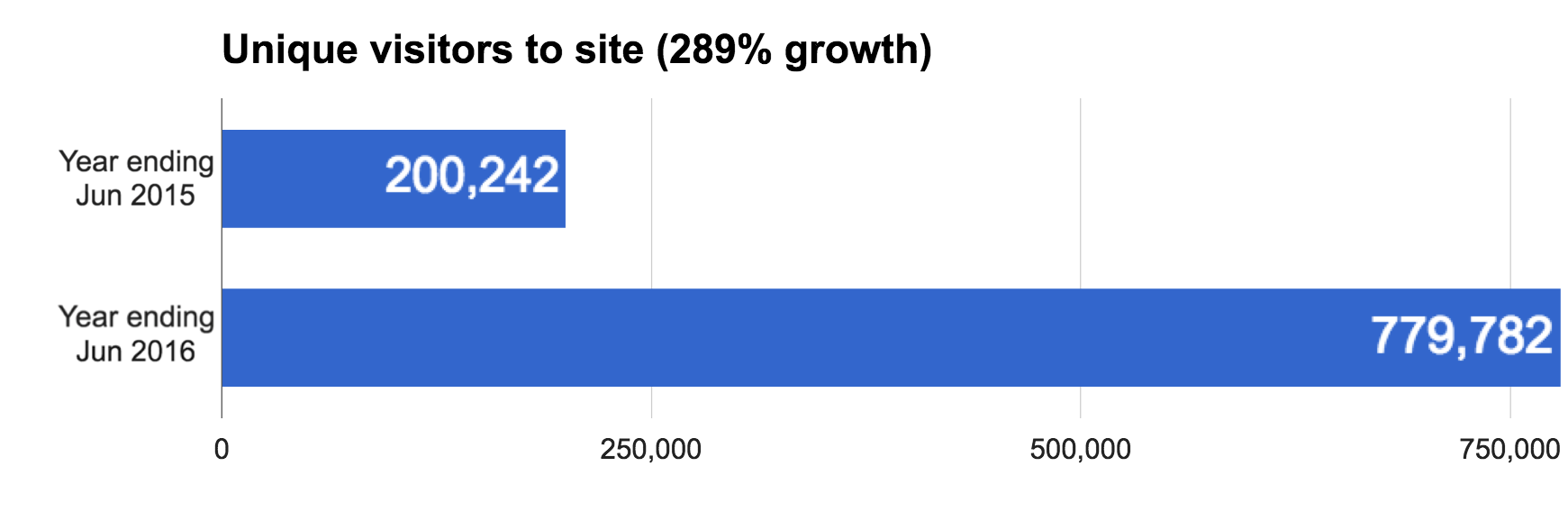

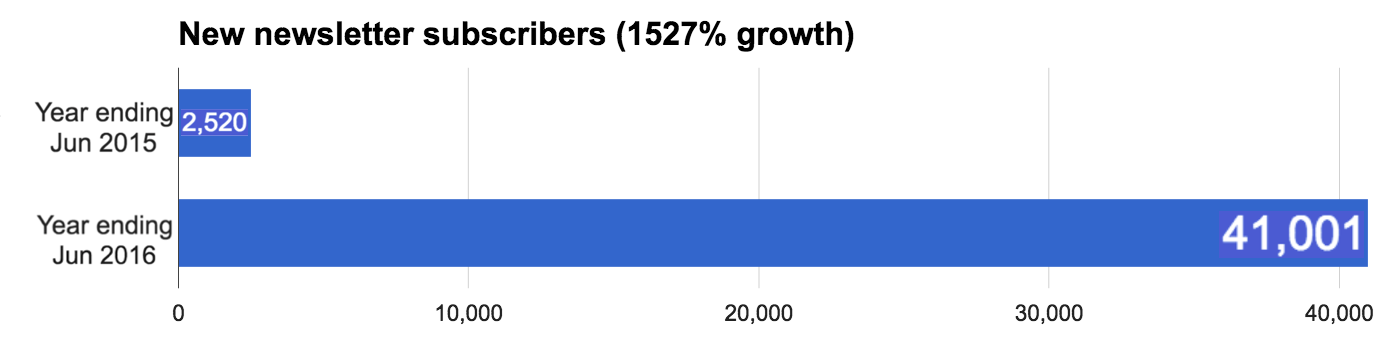

How much should you believe the numbers in figures like this?

How much should you believe the numbers in figures like this?

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king – or so the saying goes. In his new book, Deep Work, Cal Newport argues that when it comes to deep concentration, we have become the land of the blind.

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king – or so the saying goes. In his new book, Deep Work, Cal Newport argues that when it comes to deep concentration, we have become the land of the blind.