Annual review December 2017

NOTE: This piece is now out of date. More current information on our plans and impact can be found on our Evaluations page.

Summary

This year, we focused on “upgrading” – getting engaged readers into our top priority career paths.

We do this by writing articles on why and how to enter the priority paths, providing one-on-one advice to help the most engaged readers narrow down, and introductions to help them enter.

Some of our main successes this year include:

- We developed and refined this upgrading process, having been focused on introductory content last year. We made lots of improvements to coaching, and released 48 pieces of content.

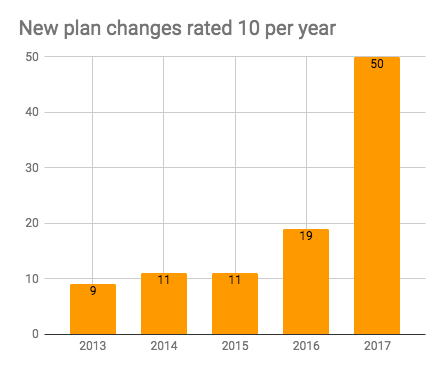

- We used the process to grow the number of rated-10 plan changes 2.6-fold compared to 2016, from 19 to 50. We primarily placed people in AI technical safety, other AI roles, effective altruism nonprofits, earning to give and biorisk.

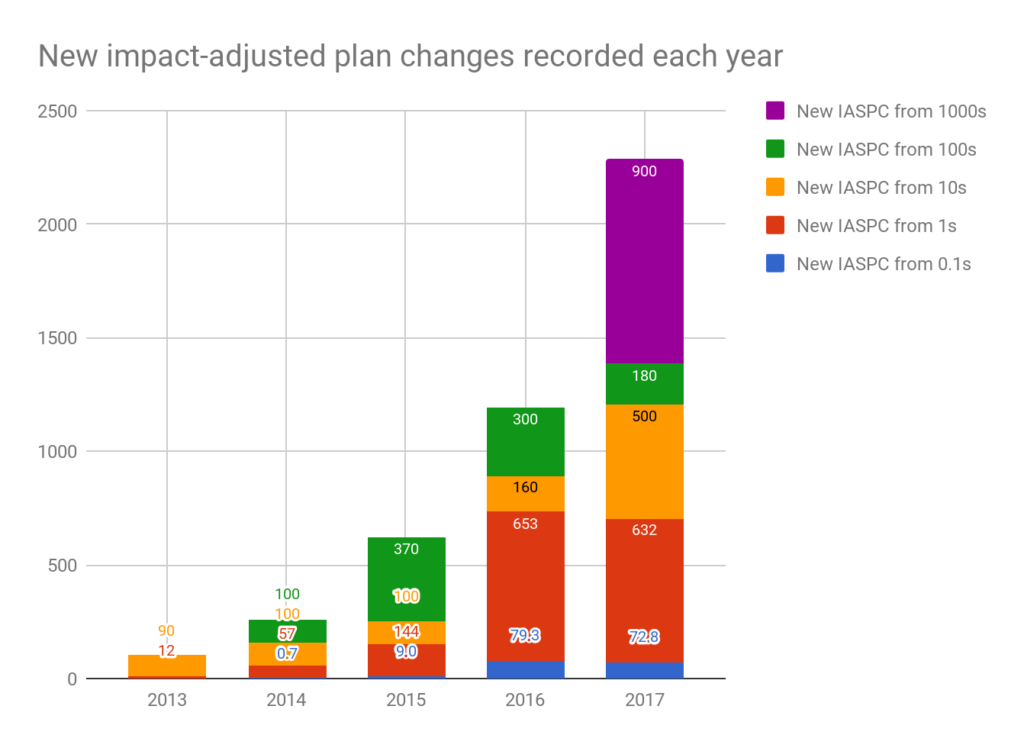

We started tracking rated-100 and rated-1000 plan changes. We recorded 10 rated-100 and one rated-1000 plan change, so with this change, total new impact-adjusted significant plan changes (IASPC v2) doubled compared to 2016, from roughly 1200 to 2400. That means we’ve grown the annual rate of plan changes 23-fold since 2013. (If we ignore the rated-100+ category, then IASPCv1 grew 31% from 2017 to 2016, and 12-fold since 2013.)

This meant that despite rising costs, cost per IASPC was flat. We updated our historical and marginal cost-effectiveness estimates, and think we’ve likely been highly cost-effective, though we have a lot of uncertainty.

We maintained a good financial position, hired three great full-time core staff (Brenton Mayer as co-head of coaching; Peter Hartree came back as technical lead; and Niel Bowerman started on AI policy), and started training several managers.

Some challenges include: (i) people misunderstand our views on career capital so are picking options we don’t always agree with (ii) we haven’t made progress on team diversity since 2014 (iii) we had to abandon our target to triple IASPC (iv) rated-1 plan changes from introductory content didn’t grow as we stopped focusing on them.

Over the next year, we intend to keep improving this upgrading process, with the aim of recording at least another 2200 IASPC. We think we can continue to grow our audience by releasing more content (it has grown 80% p.a. the last two years), getting better at spotting who from our audience to coach, and offering more value to each person we coach (e.g. doing more headhunting, adding a fellowship). By doing all of this, we can likely grow the impact of our upgrading process at least several-fold, and then we could scale it further by hiring more coaches.

We’ll continue to make AI technical safety and EA nonprofits a key focus, but we also want to expand more into other AI roles, other policy roles relevant to extinction risk, and biorisk.

Looking forward, we think 80,000 Hours can become at least another 10-times bigger, and make a major contribution to getting more great people working on the world’s most pressing problems.

We’d like to raise $1.02m this year. We expect 33-50% to be covered by Open Philanthropy, and are looking for others to match the remainder. If you’re interested in donating, the easiest way is through the EA Funds.

If you’re interested in making a large donation and have questions, please contact [email protected].

If you’d like to follow our progress during the year, subscribe to 80,000 Hours updates.

Table of Contents

- 1 Summary

- 2 Key summary metrics

- 3 What is 80,000 Hours?

- 4 How our strategy and plans changed over the year

- 5 Progress 1: upgrading programmes

- 6 Progress 2: introductory programmes

- 7 Progress 3: research

- 8 Progress 4: capacity-building

- 9 Historical cost-effectiveness

- 10 Marginal cost-effectiveness

- 11 Mistakes and issues

- 11.1 People misunderstand our views on career capital

- 11.2 Not prioritising diversity highly enough

- 11.3 Set an unrealistic IASPC target

- 11.4 Not increasing salaries earlier

- 11.5 Rated-1 plan changes from online content not growing

- 11.6 Accounting behind

- 11.7 Not being careful enough in communication with the community

- 11.8 Poor forecasting of our coaching backlog

- 11.9 Maybe not focusing enough on “rated-1000” plan changes

- 11.10 Maybe not focusing enough on maintaining credibility as opposed to getting traffic

- 12 Risk-analysis: how might 80,000 Hours have a negative impact?

- 13 Plan for the next year

- 14 Financial report

- 15 Why donate to 80,000 Hours

- 16 Next steps

In the rest of this review, we cover:

- A summary of our key metrics.

- What we do, and how our plans changed over the year.

- Our progress over the year, split into upgrading, introductory, research and capacity building.

- Updated estimates of our historical and marginal cost-effectiveness.

- Mistakes, issues and risks.

- Our plan for the next year.

- Our financial situation and fundraising targets.

See our previous annual reviews.

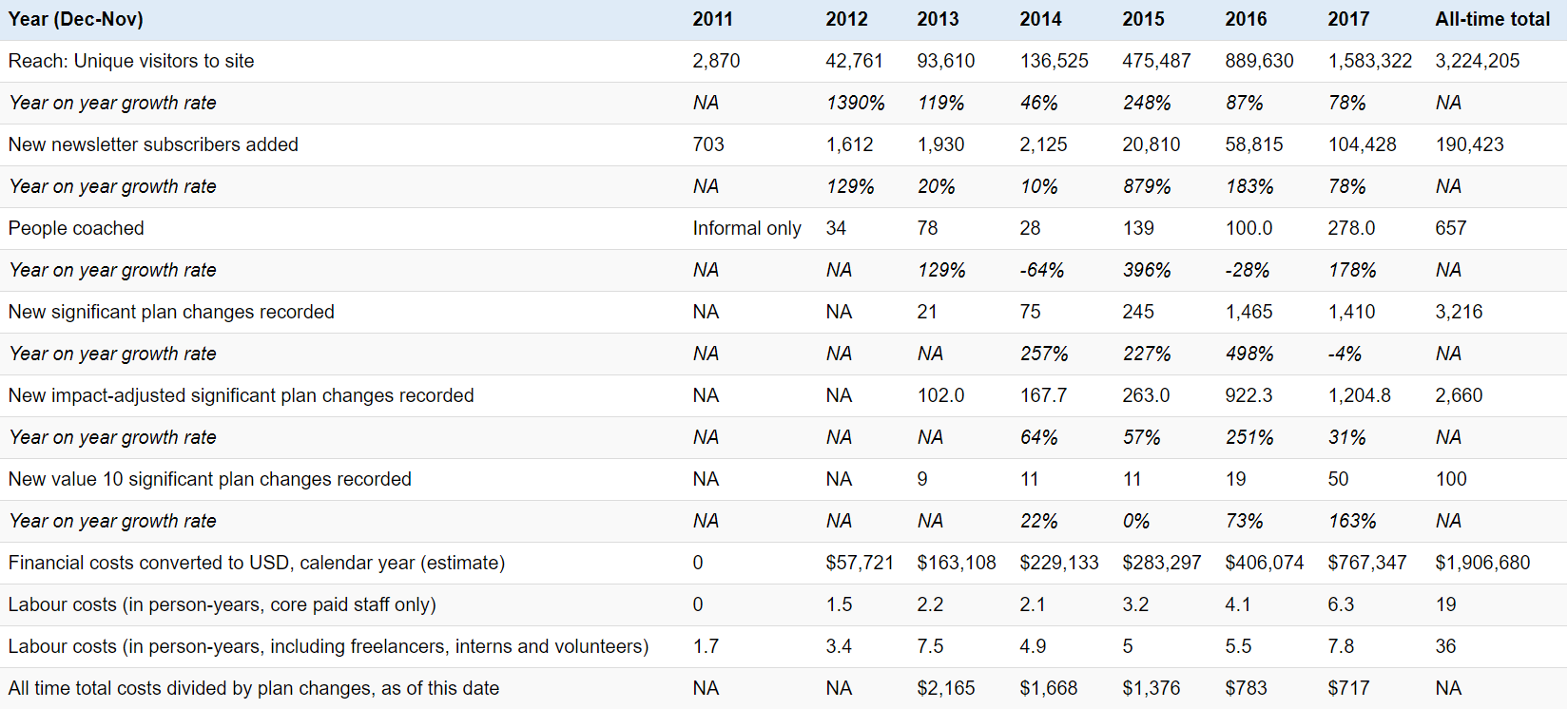

Key summary metrics

Plan changes

Our key metric is “significant plan changes”. We count one when someone tells us they switched their plans from path A to B due to us, and expect to have a greater social impact as a result.

We track the total number, but we also rate the plan changes 0.1 / 1 / 10 depending on their size and expected impact, and track the total in each category. Read more about the definition of significant plan change, and impact-adjustment.

This year, we decided to focus on plan changes rated 10, and we grew these 163% from 19 newly recorded in 2016 to 50 recorded this year.

However, plan changes rated 0.1 and 1 declined 8% and 3% respectively as we stopped focusing on them.

We also track the “impact-adjusted” total (the weighted sum), which grew 31%. However, this year we became more confident that the plan changes rated 10 are more than 10 times higher impact than those rated 1, perhaps 100 times more, so this undercounts our growth.

See a summary of all these metrics in the table below. Bear in mind, they’re highly imperfect proxies of our impact — we go into more detail in the full section on historical cost-effectiveness.

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | All time total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total new significant plan changes | 21 | 75 | 245 | 1465 | 1410 | 3216 |

| Yearly growth rate | 257% | 227% | 498% | -4% | ||

| Rated 0.1 | 0 | 7 | 90 | 793 | 728 | 1618 |

| Yearly growth rate | 1186% | 781% | -8% | |||

| Rated 1 | 12 | 57 | 144 | 653 | 632 | 1498 |

| Yearly growth rate | 375% | 153% | 353% | -3% | ||

| Rated 10 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 19 | 50 | 100 |

| Yearly growth rate | 22% | 0% | 73% | 163% | ||

| Impact-adjusted total | 102 | 168 | 263 | 922 | 1205 | 2660 |

| Yearly growth rate | 64% | 57% | 251% | 31% |

The reporting period ends in Nov each year

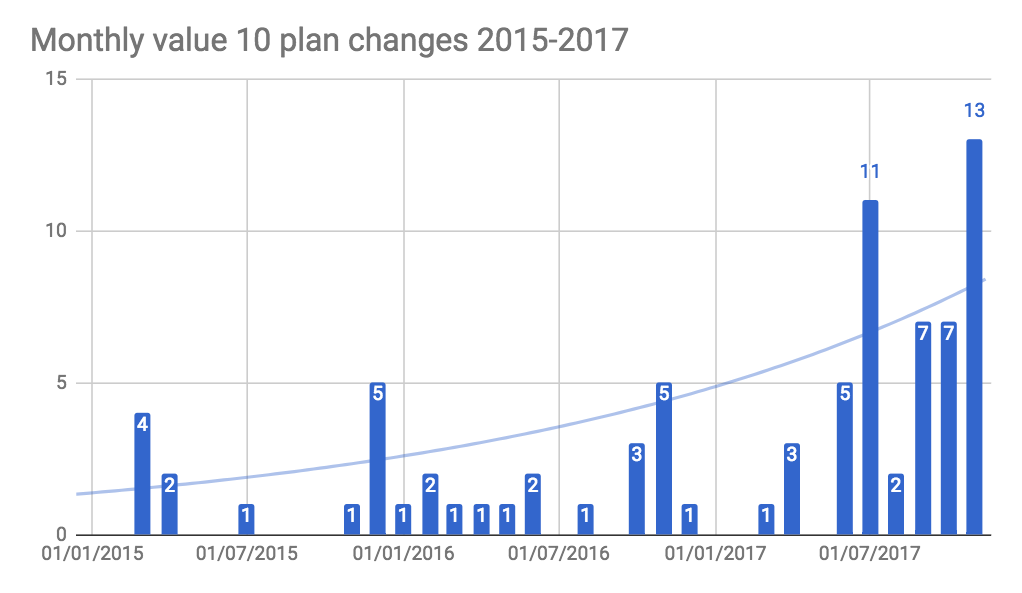

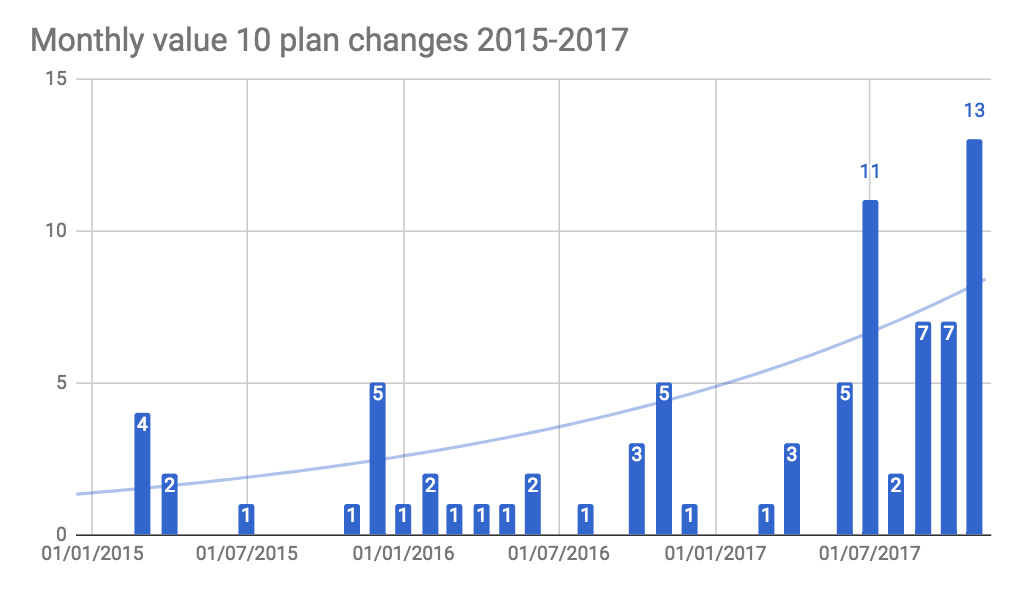

Here are annual and monthly growth charts for new plan changes rated 10.

Using a Dec-Nov year for these figures.

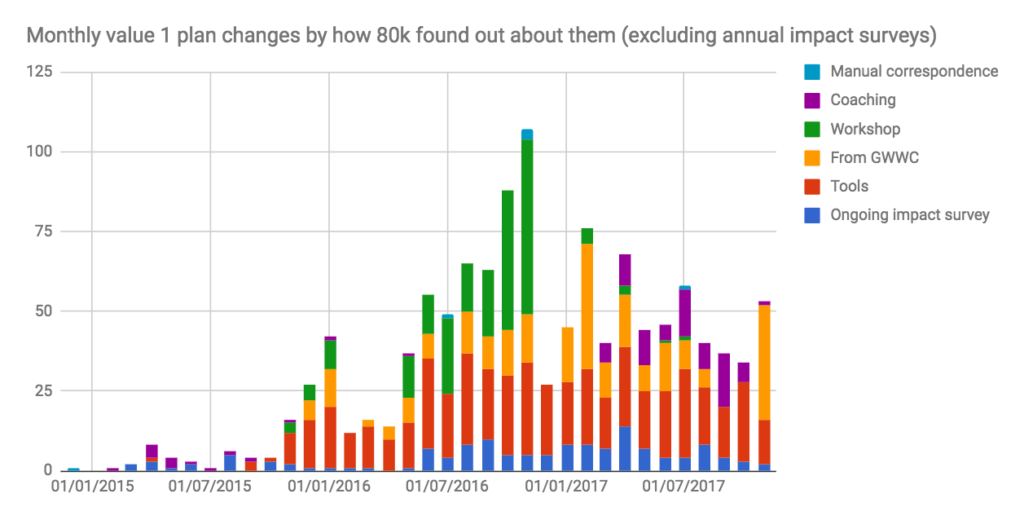

Below is the monthly growth chart for plan changes rated 1. As we stopped improving and driving traffic to our introductory content, plan changes driven by online sources stayed flat, while those from workshops went to zero because we stopped giving workshops.

Adjusted plan change weightings

This year we became more confident that the plan changes rated 10 should be split into 10/100/1000. Below, we have reconstructed our past metrics to show roughly how they would have looked if we’d used these categories too. (Note that if a change is recorded as 10 in 2015 and then re-rated 100 in 2016, it’ll appear in both years as +10 and +90)

| Plan change rating | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total significant plan changes | 21 | 75 | 248 | 1465 | 1414 | 3223 |

| Rated 0.1 | 7 | 90 | 793 | 728 | 1618 | |

| Rated 1 | 12 | 57 | 144 | 653 | 632 | 1498 |

| Rated 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 16 | 50 | 95 |

| Rated 100 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 11 | |

| Rated 1000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Summary funnel figures

The table below shows some key metrics earlier in the funnel (i.e. website visitors, new newsletter subscribers, people coached), and our financial and labour costs.

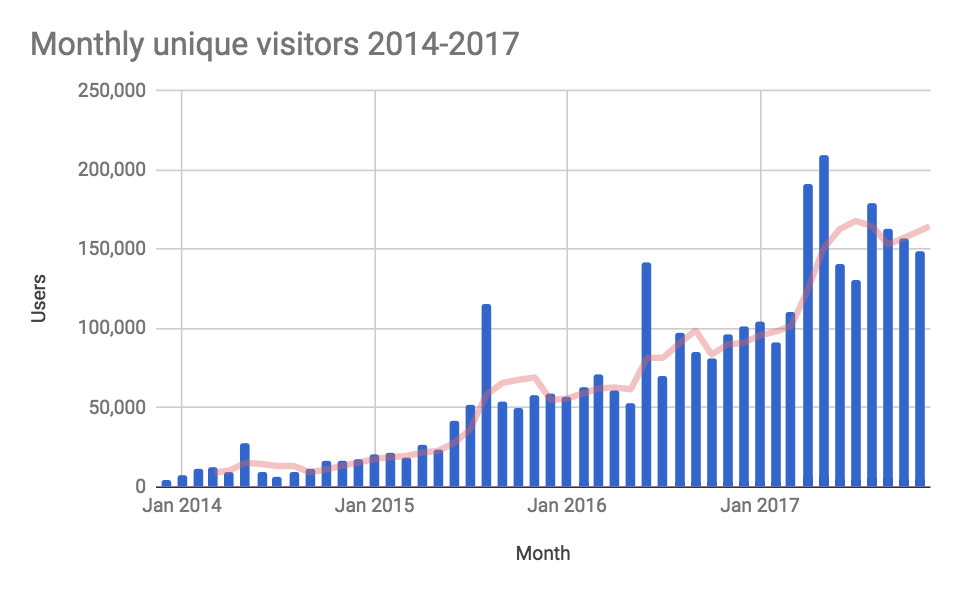

Traffic continued to grow as we released 48 new or updated pieces over the year – the most we’ve released in a year.

New newsletter subscribers grew 80%, but most of this was due to a spike in December 2016 – they have been flat otherwise because we’ve been directing traffic towards coaching rather than the newsletter.

The number coached almost tripled as we switched from workshops to coaching.

Our costs slightly more than doubled, as we grew the team (an average of 1.3 full-time staff extra over the year, as well as 1.5 full-time staff worth of freelancers), raised salaries and moved to the Bay Area.

The reporting period ends in Nov each year, apart from the last three rows which use a Jan-Dec reporting period.

What is 80,000 Hours?

80,000 Hours aims to get talented people working on the world’s most pressing problems.

Many people want to do good with their careers, but currently there’s no clear source of research-backed advice on how to do this most effectively.

We aim to provide this advice, by:

- Doing research to work out which career opportunities are highest-impact, and how individuals can fill them.

Producing online content to bring people to our site, and tell them about these opportunities and how to enter them.

Providing in-person advice to help our most engaged readers narrow down these options, enter them, and join the effective altruism community.

Each aspect is complementary with the next. The research informs the online content; the online content brings people into the in-person advice and makes it faster to give; and speaking in-person helps us prioritise the research.

We do this work in the context of the rest of the effective altruism community. We see our role in the community as helping to allocate human capital as effectively as possible, which we think is especially important because the community is currently more skill-constrained than funding constrained.1 We aim to be the “Open Philanthropy of careers”.

As part of our coordination with the community, we work closely with the Centre for Effective Altruism, and are legally part of the same entity, though for most intents and purposes operate as an independent organisation (fiscal sponsorship). Read CEA’s independent annual review.

Our programmes (online content and in-person advice) aim to take people all the way from the point at which they have a vague idea they want to do good but no specific plans, all the way to having a job in our priority career paths and in-depth knowledge of effective altruism.

Roughly, we divide this process into two stages, “introductory” and “upgrading”:

| Introductory stage | Upgrading stage | |

|---|---|---|

| How do we do it? | Online career guide | Advanced online content & one-on-one advice (inc. community introductions) |

| What changes in this stage? | ||

| Knowledge | Learn about the basic principles in our career guide. | Learn about our priority paths and advanced research. |

| Motivation | Become somewhat more focused on social impact. | Make social impact a key career goal. |

| Community connections | Make some initial connections. | Make several strong connections. |

| Recorded output: plan change | Report a small plan change (rated 1 or 0.1) e.g. change graduate programme, take the GWWC pledge, aim towards a priority path in 3yr. | Successfully enter one of our priority paths, or other high-impact option. Report a large plan change (rated 10) |

In 2016, we tripled the number of plan changes rated 1, while the number rated 10 only increased 73%, so we assessed that upgrading was the key bottleneck. So, in our 2016 annual review, we decided to focus on the upgrading stage rather than introductory.

How our strategy and plans changed over the year

There were two main ways our strategy changed: (i) we switched our target from tripling IASPC to growing rated-10 plan changes 2.5-fold, and (ii) in order to do this, we stopped giving workshops and resumed one-on-one coaching. We’ll explain each in turn.

Despite deciding to focus on upgrading, we set an aggressive target to triple the total number of impact-adjusted significant plan changes (IASPC), matching our performance in 2016.

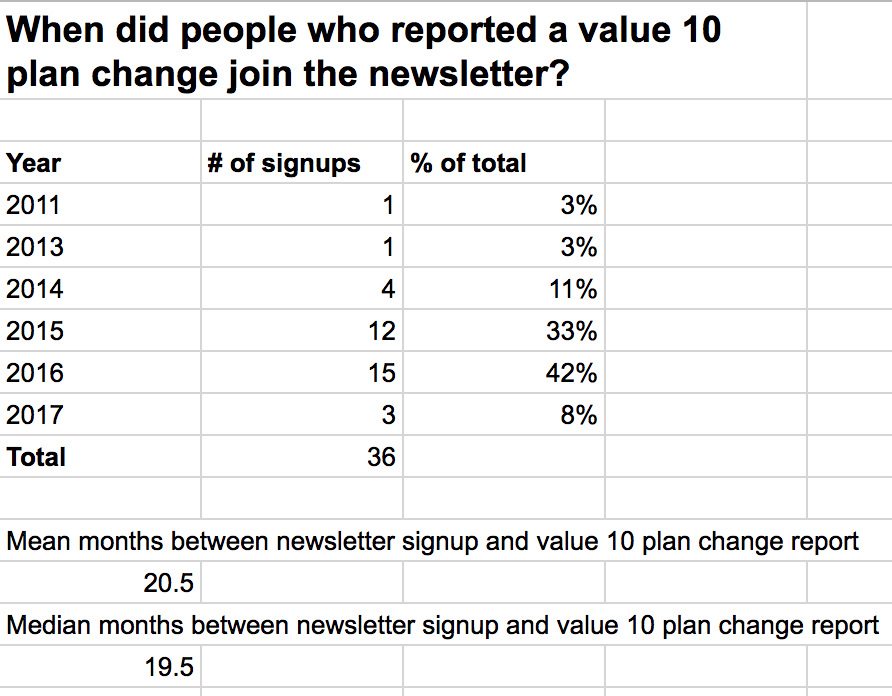

However, it takes a long time to get plan changes rated 10 (our latest estimate is about 2 years from joining the newsletter on average), and many of the projects we listed in the annual review were more helpful in finding rated-1 rather than rated-10 plan changes.

What’s more, we realised that some plan changes rated 10 are actually worth more like 100 times those rated 1. This meant that the IASPC metric, as defined at the start of 2017, undercounts the value of growth from plan changes rated 10.

As a result, we decided to drop the target, and we would have failed to make it. (Though, we did complete 4 out of 5 of the specific projects we listed in our 2016 plans – improving career reviews, mentor networks, user tracking and some efforts to make the guide more engaging; and in addition one major marketing experiment.)

Instead, from June 2017, we decided to only focus on growing the number of plan changes rated 10, setting a target of 40 over the year, up from 19 in 2016. We exceeded this target, reaching 50 by the end of November. Going forward, we also intend to revise the IASPC metric so that it better captures the value of the top plan changes, and then return to using IASPC to set our goals.

As part of this shift to rated-10 plan changes, in February we also decided to shift the in-person team fully towards one-on-one advice, and stop giving workshops. This was for a number of reasons.

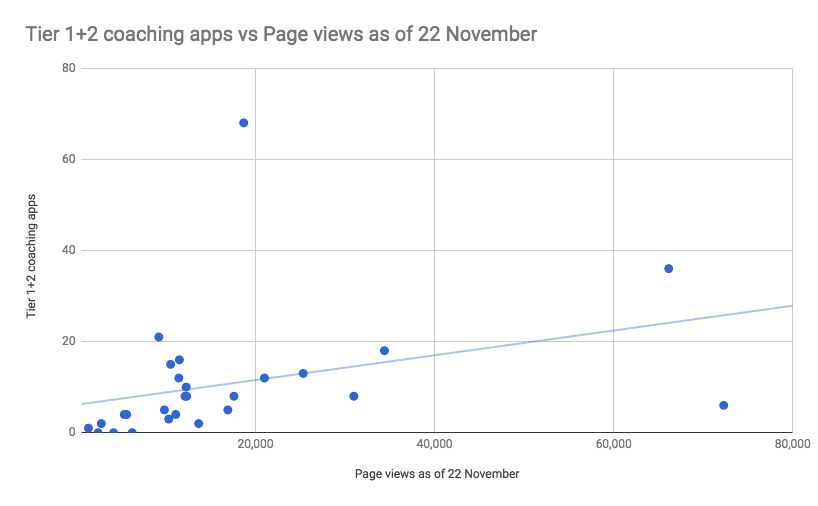

One was that we realised that if we put specific appeals on specialist content, we could find very high potential people to coach. For instance, at the end of our AI problem profile, we say “Want to work in AI safety? We can help.” Since this profile receives about 3000 unique views per month, this throws up 1-2 great coaching candidates each month.

We then found that if we coached these people, we’d get more impact-adjusted plan changes per hour than if we gave workshops, and many more plan changes rated 10. Although we can only deliver one-on-one advice to a smaller number of people, the narrower targeting turns out to more than offset this downside, making the one-on-one more effective overall.

After we realised this, we put two full-time staff on one-on-one advice, and made improving the process one of our top priorities.

Now we’ll outline the progress we made this year in more depth. Then we’ll analyse our cost-effectiveness and then plans for next year.

We divide our progress into four categories of work, which we cover in sequence:

- Upgrading – helping engaged users enter our priority career paths.

- Introductory – telling new people about our basic ideas.

- Research – to identify the highest-impact career opportunities.

- Capacity building – to increase the abilities of the team in the long-term.

Progress 1: upgrading programmes

What process did we focus on after June to help with upgrading?

Probably our most significant progress this year was developing the following upgrading process – in brief, we promote a list of priority paths, then give people one-on-one help entering them.

We think the process is cost-effective and scalable, and it drove 4.4-fold growth in how many plan changes rated 10 we track each month compared to the start of the year.

Here’s how the approach works in a little more depth:

- In our research, we agree on a list of ‘priority paths’ — career types we’re especially excited about that people usually don’t consider. See a rough list here.

- We write up online content that makes the case for these paths, and then explains who’s well suited and how to enter. These are mainly career reviews and problem profiles, as well as our podcast.

- Promote this content to our existing audience and the effective altruism community.

- Ask the readers to apply to coaching, and spot the people we can help the most.

- Give these people one-on-one help deciding which path to focus on, introductions to people in these areas, and help finding specific jobs and funding opportunities.

- Track plan changes from this group.

Here’s a rough user flow:

Here’s how the one-on-one advice works:

- People apply and we select those we’re best placed to help and who have the best chance of getting into our priority paths.

- They fill out preparatory work, writing out their plans and questions for us.

- We do a 30-60 minute call via Skype. Initially we focus on helping them answer key uncertainties to narrow down their options, and recommending further reading. Then, we focus on helping them take action, by making introductions to specialists in the area, as well as specific jobs and sources of funding.

- With some fraction, we continue to follow up via email, and may arrange further meetings.

- We aim for them to continue to engage with mentors and people in the effective altruism community.

Here are the key funnel metrics in Sept 2017, which was typical month near the end of the year.

| Stage | Number in Sept 2017 | Conversion rate from previous stage | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a) Reach - unique visitors to entire site | 162,640 | Note that 60% of these are new readers; while it takes over a year on average to make a big plan change. | |

| 2) Unique visitors who spent at least 5 mins reading a problem profile or career review | 3,042 | 2% | Note that not all of these are priority paths. |

| 3) Coaching applications | 225 | 7% | |

| 4) Tier 1 coaching applicants | 43 | 19% | The top ~20% of applicants that we want to coach. |

| 5) People coached | 41 | 95% | |

| 6a) Expected rated-10 plan changes in 6 months | 4.1 | 10% | Based on recent conversion rates this year |

| 6b) Expected rated-10 plan changes in 18 months | 8 | 20% | Rough estimate. We expect further increases after this. |

| 6c) Actual rated-10 plan changes recorded this month | 7 | 17% | Note that most of these were from coaching in previous months |

| Total financial costs per month/$ | 65,000 | Much of this spent on investment rather than getting short-term plan changes.. | |

| Ratio of costs per expected plan change rated 10 in 18 months/$ | 8100 | Overestimate of cost to cause a plan change (explained below under “costs”). |

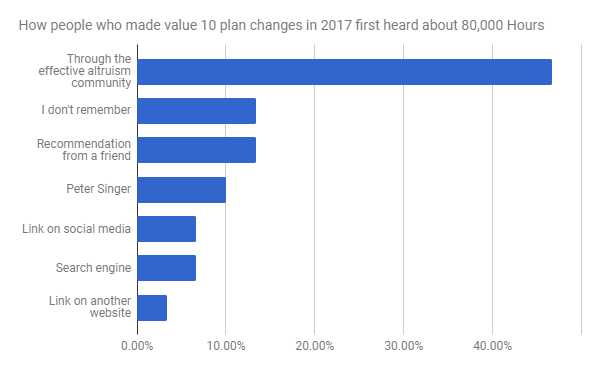

This is how people who made plan changes first found out about 80,000 Hours:

The EA community dominates because we mainly coach people who have some kind of involvement in the community (and only 10% of people involved in the community first found out about it from us).

On average it takes about 2 years between someone first engaging on the website and reporting a rated-10 plan change, so the people who are reporting plan changes today are those who first started reading in 2015 (when our traffic was about one third the size). This is both because it takes people time to change their minds and because it takes us time to learn about their shift.

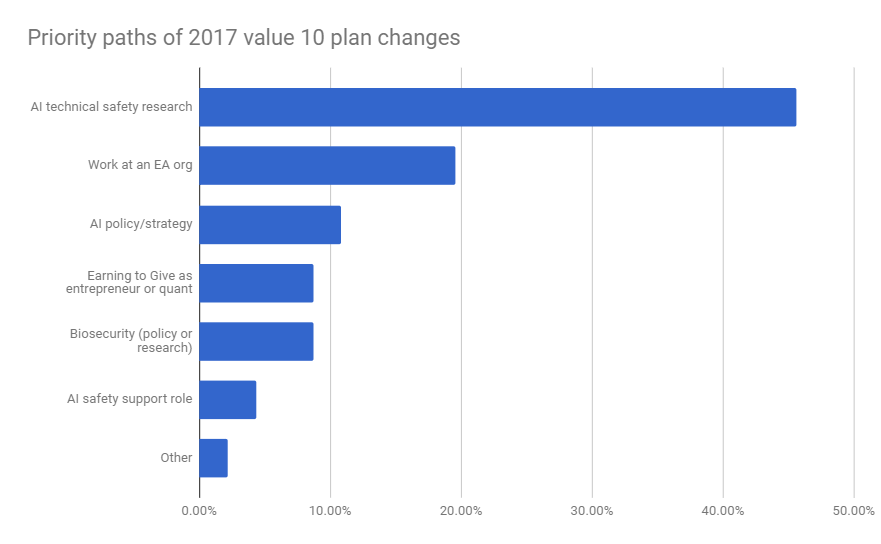

What did the plan changes consist of?

What follows is more explanation of what these shifts typically involve.

Our largest focus area this year was AI technical safety, since we thought it was the most urgent area where we could make a contribution.

Over half of the technical AI safety plan changes come from people with a pretty similar story. Typically, they’re in their early-mid 20’s and studied a quantitative subject at university. They’ve come across effective altruism before, but were not actively involved. They read our online content on AI safety and found it significantly more concrete in terms of next steps than other resources, decided they might be a good fit, and applied for coaching.

During coaching, we helped them think about their personal fit relative to other options, gave them further reading (such as our AI safety syllabus and CHAI’s bibliography) and introduced them to mentors and the AI safety community (e.g. David Kruger, a PhD candidate at MILA and FHI intern).

There are now over 15 people aiming to do technical AI safety research due to 80,000 Hours at graduate school, often at top labs (such as UC Berkeley’s CHAI). One has already published an AI safety paper and another three are working on their own. We can give further details on request.

Turning to AI policy/strategy, two were already working in government, but after reading our content (such as our AI policy guide) and speaking with us, they’re planning to focus more on AI safety. Three are at top universities, but have switched their focus to AI policy/strategy, and are already working with some of the leaders in the field (e.g. Allan Dafoe). Of these, two decided to get PhDs (in law and political science) to get into a better position to make a difference long-term.

AI support roles usually mean operations and management roles at AI research organisations. These people come from a wide variety of backgrounds. They have a similar degree of interest in AI safety, but have a more generalist skill-set as opposed to academic.

Outside of AI, the next largest group is people who took jobs at effective altruist organisations. Of the nine people working in effective altruist orgs, three were already fairly involved in the community – we helped by telling them about a job they might be a good fit for, which they landed. The other six attribute their plan changes to 80,000 Hours for a miscellaneous set of reasons, for instance, reading our website changed their minds about which problem to work on, we got them more involved in the community in general, and so on.

The biorisk plan changes are typically from people who weren’t planning on working in this field, had completed an undergraduate degree in a related area (e.g. medicine) and were already interested in effective altruism but not sure how to contribute. We told them about how to contribute (e.g. in our podcasts on biorisk) and put them into contact with people working in the area.

The final major category is people who switched to earning to give. Three of them are in tech entrepreneurship and one in quant trading.

Note that because so many of the plan changes are doing graduate study to enter research, many are not already having an immediate impact. We roughly estimate:

- 30% have changed their plans but not yet passed a major “milestone” in their shift. Most of these people have applied to a new graduate programme but not yet received an offer.

- 30% have reached a milestone, but are still building career capital (e.g. entered graduate school, or taken a high-earning job but not yet donated much).

- 40% have already started having an impact (e.g. have published research, taken a nonprofit job).

This is different from previous years, when fewer plan changes were focused on research, and so a greater fraction were able to have an impact right away. In 2016, we rated 18% as pre-milestone, 11% as post-milestone and 72% as already having an impact.

If you’re interested in making a donation over $100,000, we can provide detailed case studies of individual of plan changes (with permission of the people involved of course). Please contact [email protected].

Growth rates

At the start of the year, we were only tracking about one rated-10 plan change per month. Over 2016, our average was 1.6. We’ve now held above 7 the last three months, making for 4.4-fold growth compared to the start of 2017, comparing month on month (year on year growth was 2.6-fold).

Note that the months in which we recorded 11 and 13 were partly inflated because we made extra effort to assess our impact in these months, and we count plan changes on the month we find out about them (as opposed to the month we cause them). Excluding these extra efforts, they would have been in line with the other months at around 7 per month.

Costs and cost-effectiveness

This year, we put the bulk of core team time into this upgrading process. Here’s a breakdown of how we spent the time:

- Rob & Roman: producing and promoting online content on priority paths.

- Peter M & Brenton: giving and improving the one-on-one advice.

- Peter H: improving systems and metrics for the above.

- Ben: 35% managing the team; 35% external relations; 30% online content (a mixture of intro and advanced).

In the funnel table above, we estimated that our work in September 2017 will cause 8 value 10 plan changes within the next 18 months, compared to financial costs of $65,000, or $8,100 per change.

We expect the number and value of plan changes will continue to increase after this point, since we’ve seen many cases where it took more than 2 years to record a plan change. We also expect the efficiency of the process to continue to increase as we improve the coaching and content. So, we expect the costs to be below $8,100 per change longer term.

What’s the value of the plan changes? We’ll cover that later in this report. Additionally, bear in mind that we also produce plan changes rated 1, and other forms of value, such as growing the effective altruism community, which are being ignored here.

What were the main ways we improved the upgrading process during year?

Once the upgrading process was solidified around June, we made a number of improvements, including:

Released more online content on priority paths:

- 15 podcasts, of which 10 were on top priority paths.

- Relevant career reviews and articles:

- Relevant problem profiles:

- Other articles:

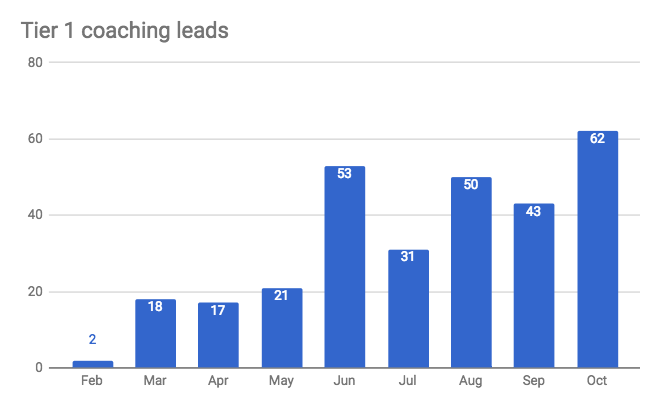

Most of this content contained appeals to apply to coaching. These appeals, combined with traffic growth, helped us to grow the number of “tier 1” coaching applications (the cutoff for receiving coaching, and roughly the top 20% of applicants) from zero to about 50 per month. Other major sources included EAG conferences and word-of-mouth.

| Source of tier 1 coaching leads | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Online call-to-action | 132 | 48% |

| EAG | 62 | 23% |

| Online plan change report | 17 | 6% |

| Referral | 15 | 5% |

| Asking them one-on-one | 8 | 3% |

| Unknown | 40 | 15% |

| Grand Total | 274 | 100% |

We also improved the one-on-one advice in several ways:

- Brenton started as a full-time coach in February, joining Peter, and was trained to the point where he gets similar results.

- Peter and Brenton were new to coaching at the start of the year, so have learned a lot about how to do it, and gained expertise on and connections within the priority paths.

- We iterated the application process, to get better at selecting people (though it’s too early to see clear results).

- We secured 3 extra paid specialist mentors (compared to 1 last year), who we refer people to after they get coaching.

- We started tracking coaching in our CRM (customer relationship manager system), which means that everyone on the team can see who has been coached, and we save all the key data, including how many hours we spend with each person, so we can estimate plan changes per hour.

- We made lots of tweaks to streamline the process, making it faster to assess applications, schedule coaching sessions and create prep documents.

We also ran several experiments of major new features:

- Peter M spent 3 weeks focused on headhunting for specific top jobs. This led to 2 successful job placements and seven trials, which was better than our expectations. So, we intend to put more effort into headhunting in the future, with an initial focus on collecting better data on the people we coach to make it easier to do an initial cut-down.

We launched a job board that highlights about 10 especially promising job opportunities. It’s received over 70,000 views, and now generates several applications for coaching each week. However, we’re not aware of any clear cases of people switching jobs due to it, so we don’t intend to increase investment in it.

We spent several weeks exploring the idea of turning the coaching into a “fellowship”, where we admit a smaller number of people who receive a greater level of ongoing support, as well as introductions to each other. We still think this is promising, and intend to do more experiments over the next year.

We hired Niel Bowerman to work full-time as an AI policy specialist, since it’s one of the highest-priority and most neglected areas. If this works well, it could be a route to scaling the process: we could have 2-3 “generalist” coaches, who send people on to “specialists” in several key areas.

We think there are many more avenues for making the process more efficient and scaling up its impact, as we cover in the plans section later.

Progress 2: introductory programmes

Upgrading was the main way we aimed to increase our impact this year, but as covered earlier, we also have additional impact through “introductory” programmes.

How do our introductory programmes work, and what impact do they have?

Our main introductory programme is our online career guide, which aims to introduce people to our key advice and effective altruism in general.

Here is an overview of the funnel, again for Sept 2017:

| Sept 2017 | Conversion from previous main step | |

|---|---|---|

| 1a) Reach - new visitors | 145,506 | |

| 1b) Reach - returning visitors | 41,255 | 28.4% |

| 2a) Engagement - Newsletter signups | 6,698 | 16.2% |

| 2b) Engagement - Unique visitors that spent more than 5 minutes reading career guide | 6,251 | 15.2% |

| 3a) Plan change reports (not via coaching or events) | 353 | 5.3% |

| 3c) Confirmed plan changes rated 1 | 37 | 0.6% |

| 3b) Confirmed plan changes rated 1 (not via coaching or events) | 20 | 0.3% |

| 3c) Confirmed plan changes rated 0.1 (not via coaching or events) | 46 | 0.7% |

The introductory programmes create value in several ways:

- Through the direct impact of extra donations and improved career choices.

- By finding people who later “upgrade”, as in the previous section. In 2017, 69% of plan changes rated 10 were previously rated 1, and on average people have read the site for two years before being confirmed as a rated-10 plan change.

- By introducing people to the effective altruism community and growing it.

On the latter, several surveys suggest 80,000 Hours is probably responsible for involving about 5-15% of the members of the effective altruism movement:

- The 2017 Effective Altruism survey found that 7.2% of respondents (94) first heard about EA from 80,000 Hours, and the annual rate had grown 4-fold since 2014. 80,000 Hours was also the third most important way people “got involved” in EA, after GiveWell and “books or blogs”.

As covered in the same post, in a poll on the EA Facebook group, 13% of respondents cited 80,000 Hours as the way they first found out about effective altruism.

In a survey of participants of EAG London 2017, 9% said they found out about EAG through 80,000 Hours, and we’ve been told similar or larger figures at previous EAG conferences.

If we look directly at the rated-1 and rated-0.1 plan changes, it seems likely that they include hundreds of people who became more involved in effective altruism due to 80,000 Hours (figures below). If there are several thousand “engaged” community members who have made significant changes to their lives, then this would again suggest 5-15% are due to 80,000 Hours.

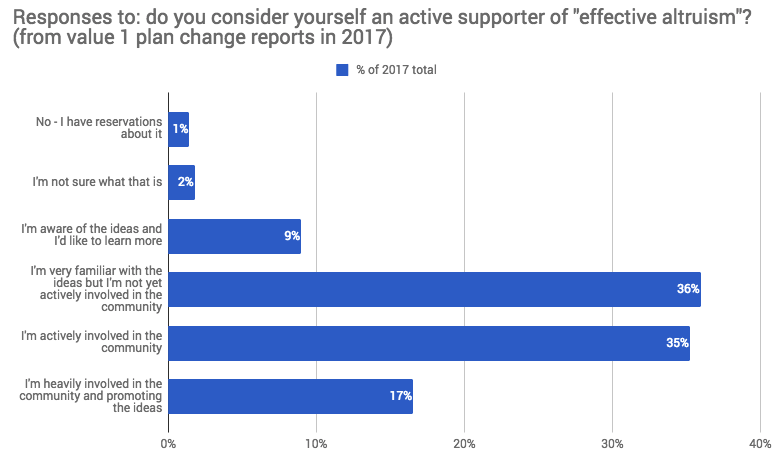

The results of our survey of rated-1 plan changes:

| Number | Percentage of previous category | |

|---|---|---|

| Rated-1 plan changes in 2017 | 612 | |

| Answered the question “do you consider yourself an active supporter of effective altruism?” | 453 | 74% |

| Said they’re “actively involved” in the community. | 148 | 33% |

| Answered the follow up question “Did you get involved in the effective altruism community because of 80,000 Hours?” | 70 | 47% |

| 1) Said "80,000 Hours made it more likely, but wasn’t the main reason I got involved" | 25 | 36% |

| 2) Said “Yes, 80,000 Hours is the main reason I got involved in the community" | 13 | 19% |

| 3) Said "No, 80,000 Hours did not play a role". | 32 | 46% |

Over our entire history, we’ve recorded about 1500 rated-1 plan changes and 1600 rated-0.1 plan changes. This survey suggests that of the rated-1 plan changes, about 12.5% of these are now actively involved and got more involved due to 80,000 Hours.

What progress did we make on introductory content in 2017?

New content released

We released several career guide articles, and supplementary articles (brackets show views over the previous 12 months):

- All the evidence-based advice we found on how to be more productive (new, 176,913)

- The world’s biggest problems (new, 85,401)

- 3 ways anyone can have more impact (updated, 30,967)

- How much difference can one person make? (updated but not promoted, 49,883)

- Introduction (updated, but not promoted, 63,844)

- Why join a community (new, 16,335)

- Which skills make you most employable? (new, 67,700)

- The 11 highest-paying jobs in America (new, 28,727)

See metrics on all our key 2017 content.

We also looked into re-releasing the book, and spoke to several editors, an agent and a bestselling author. We decided to deprioritise it for now, but improved our plans for the next iteration, which we still plan to do within 3 years.

Analytics upgrades

We made major upgrades to user data tracking, to make it easier to measure our impact. For instance, we now record prior involvement with effective altruism when people first sign-up to our newsletter, so we can better separate our impact from the rest of the community.

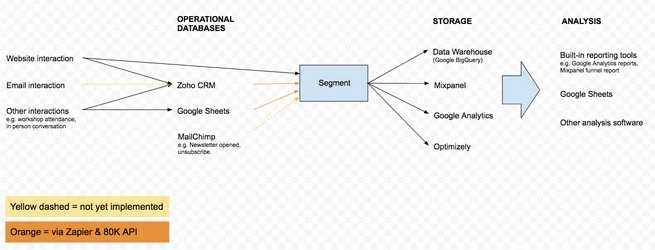

More generally, we now consolidate much more of our data, so we can analyse individual users from when they first give us their email address, to how they engage, all the way to recording plan changes. Here’s a sketch of the system:

Facebook advertising experiments

We performed an $11,000 experiment with Facebook adverts targeted at students and alumni of top universities in their 20s. We were able to gain about 3,500 newsletter subscribers (~$3/sub average, but more like $5 at the margin) after six months, leading to 13 coaching applications and 3 plan changes rated 1, as well as 8 flagged as “potential 10s”.

Our best guess is that the 2-year conversion rate of the subscribers to impact-adjusted significant plan changes will be 0.1 – 2%, making the cost of acquisition per IASPC $200-$3000.

If the costs of acquisition are 50% of total costs at the margin, the total cost per plan change would be $400-$6000. Given that our current cost is under $500, this method is probably not especially attractive.

So, we don’t intend to scale up these campaigns next year, though we are interested in running more experiments, especially with more narrowly targeted audiences.

Video guide experiment

Last year, we considered turning the career guide into a MOOC in order to increase audience size and completion rate. To test this idea, we turned one section of the guide into a 6 minute video, in the style of the Vox videos i.e. a mixture of talking to camera, archive footage and animation.

We created the video this year, but haven’t released it yet.

We learned that we can produce what we think is a high-quality video, but it took longer than we expected. In total, the cost was 2 weeks of Ben’s time, 4 months and $16,000 from the project lead (a freelancer with a film school background) and $6000 of other costs.

Many of these costs were due to set-up and learning how to make videos, so could probably be reduced by a factor of two, but turning the whole guide into videos of this style would still be a major project. Another option would be to make the videos less scripted, or to remove animation, but we think this would reduce quality significantly.

Given that we’re focused on upgrading rather than introductory content, we decided to deprioritise this project, though we’re still interested in doing it eventually.

Progress 3: research

Besides upgrading and introductory programmes, we also carry out research. Its aim is to improve the accuracy of our views about which career options and strategies are highest-impact, helping us direct people into more effective paths.

Most of our research is carried out in tandem with creating online content, and it’s hard to separate the two. We also pursue a small amount of open-ended research that isn’t related to anything we intend to publish. Overall, we’d estimate that about 5% of team time goes into research.

Here’s some of the main research progress we made this year, broken down into several categories.

Creating the priority path list

Our upgrading process (as above) focuses on certain priority paths, so it’s vital to choose the right ones.

This year, we created an explicit list for the first time. It was based on a variety of inputs, including the views of community leaders which we surveyed, and our own analysis of the key bottlenecks facing our top priority problems and an assessment where we can most easily help people enter.

As part of this, we added some roles we have not focused on as much in the past, including:

- AI safety policy

- AI safety strategy

- China expert

- Biorisk policy and research

- Decision-making psychology research and policy roles.

We also learned about many other high-level priorities for the community in our talent survey.

Improving our understanding of the priority paths

The bulk of our research efforts went into understanding the details of the priority paths, answering questions such as how to enter the path, who’s best suited to it, and what are the best sub-options.

We think this research is relatively tractable, there’s a lot more we could learn, and it has a major impact on what we advise people in-person. It could also eventually change our views about which paths to prioritise.

Most of the podcasts were in this category, as well as the career reviews and problem profiles we listed earlier in the upgrading section (and many unpublished pieces), though note that about 80% of the effort that goes into producing these is communication rather than research.

Here are some examples of questions where we improved our understanding, with relevant published work in brackets:

- What are the main pathways into AI policy? (AI policy guide)

- What are the major options in biosecurity and their pros and cons (podcasts with Howie Lempel and Beth Cameron)

- How to enter and test your fit for a Machine Learning PhD (career review)

Big picture research

We also do a little work on understanding major considerations that influence our advice. This year, we improved our understanding of the following issues (which haven’t already been covered above):

Published:

- What rules of thumb the members of a community should use to coordinate, and how they differ from what’s best if everyone acts individually. Read more (more detailed write-up still in draft)

What fraction of social interventions “work”. We found that the claim in our guide and the effective altruism community that “most social programs don’t work” is a bit overly simple and depends on the definition. Read more.

How non-consequentialists might analyse whether to take a harmful job in order to have a greater positive impact, and what to do all things considered. Read more

The degree of inequality in the global income distribution, and how it depends on the definition and dataset used. Read more

How most people think it’s incredibly cheap to save lives in the developing world, and that charities don’t differ much in effectiveness. Read more

What economists think the typical magnitude of externalities are for different jobs, and how this means they’re small compared to donations. Read more

Unpublished:

- How to quantitatively analyse replaceability using economics, and its overall decision-relevance.

When comparative advantage is important compared to personal fit, and how to evaluate it.

Progress 4: capacity-building

The capacity of the organisation is our ability to achieve our aims at scale. We break it into our team capacity and the strength of our financial situation. Recently, we’ve had a relatively strong financial situation, so team capacity is the more pressing bottleneck.

Progress on team capacity

The current team of 7 full-time core staff and Ben are satisfied and motivated. In a survey in Dec, on 1-5 point scale corresponding to very poor/poor/satisfactory/good/excellent, they answered 4.8/5 for satisfaction with their line manager, 4.8/5 for satisfaction with the organisation, and 4.5/5 for satisfaction with their role all considered.

We had several significant successes hiring full-time staff:

- Peter Hartree, our lead engineer, who was full-time on the team in 2015 but left, decided to return to near full-time.

- Brenton Mayer joined as co-head of in-person advice (along with Peter McIntyre) in February, was trained up to deliver similar results as Peter, and now plays a major role in running the service.

- Niel Bowerman, who was on the team in 2013, and then worked as Assistant Director of the Future of Humanity Institute, came back to work on AI policy. The aim of this role is to fill the most pressing talent gaps in this path, which we think is one of the highest-impact and most neglected areas.

However, we also lost one full-time staff member (Jesse, Head of Growth) as they realised the role wasn’t a good fit for their skills and interests.

We also carried out three trials with very strong candidates.

We hired several new freelancers, including:

- Richard Batty, who helped to found 80,000 Hours in 2012, and has already written several career reviews.

- Josh Lowe, an excellent editor, who’s a professional journalist.

- A research assistant & editor & writer.

- An office assistant and an office cleaner.

We completed our move to the Bay Area, securing visas for everyone on the team by April 2017, setting up our office, and doing the administration needed (though we’re yet to have the pleasure of filing our first personal US tax returns…).

We raised salaries, which we think has made the current team more satisfied and better able to save time, and also helped us to attract several potential hires.

Looking forward, Ben is near the limit of how many people he can effectively manage, so the next stage is to train other staff members as managers. We started doing that this year: Roman and Rob have started managing one freelancer, and Peter McIntyre has started managing Niel. If this goes well, we should have the option to double the size of the team over the next 1-2 years.

Progress on our financial situation

Our financial situation remains strong. In March, we achieved our expansion fundraising target of $2.1m. This gave us enough to cover our existing team, increase salaries, hire up to 4 new junior staff, expand our marketing budget, and have 12 months’ reserves at the end of 2017. So, we didn’t have to fundraise over the rest of the year.

For the first time, we also raised several commitments to donate again one year later. We intend to make greater use of multi-year commitments now we’re more established.

Making this target represented a major increase in our funding level, as shown by the following table (rough estimates of expenses and income by calendar year).2

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expenditure ($) | $57,721 | $163,108 | $229,133 | $283,297 | $406,074 | $767,347 | $1,906,680 |

| Income ($) | $70,285 | $237,074 | $325,686 | $355,689 | $388,020 | $1,989,462 | $3,366,216 |

Half of the funding came from Open Philanthropy, who made their first grant to us. Gaining them as a donor represents a major increase in our funding capacity. We also gained another new large donor ($70k+) and 15 new medium donors ($1k+).

Our funding base remains top heavy — the top 5 donors supplied 85% of the target, and almost everything came from the top 24 (who each gave over $1000). About 15% comes from former users, though we expect this to rise significantly as people get older.

Despite being top heavy, we think our funding base is strong. Many of the donors, especially Open Philanthropy, have the capacity to give much more, so could make up for the loss of one or two major donors, as well as grow our funding. Finally, we have tended to welcome one new large donor each year, and expect that to continue.

More importantly, we feel well-aligned with our donors — they’re members of our community, and if they stopped funding us, it would probably be for good reason.

Overall, we think our current donor community could, if appropriate, expand our funding several fold from today, and likely more. This means that while additional funding is helpful, we don’t see our funding model as a key bottleneck over the coming 2+ years. We discuss our fundraising targets in more detail later.

Historical cost-effectiveness

Has 80,000 Hours justified its costs over its history? We think it has, but it’s a difficult question, and we face a huge amount of uncertainty in our estimates.

In this section, we outline our total costs over history, and then outline several ways that we try to quantify our impact compared to costs. In the next section, we estimate future cost-effectiveness at the margin rather than historical. You can see our previous analysis here.

Years in vs. years out

One very rough way to estimate our effectiveness is to consider the ratio of years spent on the project to years of careers changed.

We’ve spent about 19 person-years of time on 80,000 Hours from the core team.

In that time, we’ve recorded over 3200 significant plan changes. Most of these people are in their twenties, so have over 30 more years in their careers, making for 96,000 years influenced, which is 5,000 times higher than our inputs.

You could convert this into a funding multiplier, by assigning a dollar value to each year of labour.

One response is that we mainly “speed-up” plan changes rather than causing them to happen at all, since these people might have been influenced by other groups in the community later, or come to the same conclusions on their own.3 If we suppose the average speed-up is two years (which we think is conservative), then 80,000 Hours has enabled 6,400 extra years of high-impact careers, which is 336 times inputs.

If we repeat the calculations only counting the one hundred rated-10 plan changes, then we’ve influenced 3,000 years counting 30 years each (158 times inputs) or 200 years with a two year speed-up (11 times inputs).

Given the size of these ratios, if you think our advice is better than what people normally receive, then it seems likely that we’ve been cost-effective.

However, we normally try to estimate our impact in a more precise way. In short, we try quantify all of our costs and the value of our plan changes in “donor dollars” — how much donors would have been willing to pay for them — and then compare the ratio. That’s what we’ll do in the following sections.

What (opportunity) costs has 80,000 Hours incurred?

We’ve spent about $1.9m over our history, of which over 60% was on staff salaries. See detail on historical costs.

Running 80,000 Hours also incurs an opportunity cost — our staff could have worked on other high-impact projects if they weren’t working here.

These costs are difficult to estimate, but it’s important to try if we’re to give a full picture of our cost-effectiveness.

Note that when most meta-charities report their cost-effectiveness ratio they don’t include the opportunity costs of their staff, making their cost-effectiveness ratio seem higher than it really is, especially if staff salaries are below market rates. If we correctly consider the full opportunity cost of our funding and staff, then any cost-effectiveness ratio above 1 means the project is worth doing.

How can we estimate staff opportunity costs? One method is to suppose that staff would have earned to give otherwise. In 2015, we asked our staff how much they would have donated if they were earning to give instead of working at 80,000 Hours. The average answer was $25,000 per year.

A likely better method is to suppose staff would have worked at other organisations in the community, and quantify the value they would have created there. In our 2016 community talent survey, respondents said they would have been willing to pay an average of $130,000 to have an extra year of time from their most recent hire. If 66% of our staff could have taken one of these jobs otherwise, the opportunity cost per year would be $86,000 per staff member. We assume 66% rather than 100% because 80,000 Hours creates some jobs that wouldn’t have existed otherwise.

In the 2017 survey, the organisations said they would have been willing to pay $3.6m for three extra years of senior staff time, or $1.2m per year. The equivalent for a junior staff member was $1.2m, or $400,000 per year. If we suppose 33% of our staff could have taken senior positions otherwise, 33% junior, and 33% something with low opportunity costs, then the average cost per year is $528,000 per staff member.

As a sense check, if we add $70,000 of salaries, this implies a total cost of $300 per staff hour, which seems high but not out of the question.

We also used an additional 16 years from volunteers, interns and freelancers, but these typically have lower opportunity costs relative to financial costs, so we’re not estimating them.

Putting these figures together:

| 2015 and before | 2016 | 2017 | Grand total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total full-time core staff/person-years | 9 | 4.1 | 6.3 | 19.4 |

| Opportunity cost per person-year/$ | 25,000 | 86,000 | 528,000 | |

| Total opportunity costs/$ | 225,000 | 352,600 | 3,326,400 | 3,904,000 |

| Total financial costs/$ | 733,259 | 406,074 | 767,347 | 1,906,680 |

| Total costs/$ | 958,259 | 758,674 | 4,093,747 | 5,810,680 |

Our estimates of opportunity costs have increased dramatically, and now account for far more than our financial costs. At least some of this is because the community has become much less funding constrained in recent years.

Note that technically we should calculate the present value of our costs, where costs incurred in earlier years are counted as higher, but because the majority of our costs were incurred in 2017, this won’t have much effect on the total.

Donations in kind

We also receive discounted services from companies (listed here), though for the most part, the value of these only accounts for a few percent of the budget.

One exception is that Google gives us $40,000 of free AdWords per month as part of their Grantspro program, which can be spent on keywords with a value up to $2. If valued at their nominal rate, this would be over half of our budget, though we’d never pay this much if they weren’t free.

We also receive free advice from many in the effective altruism community (many of whom are listed on our acknowledgements page), and in the past we’ve used the time of student group leaders and other volunteers. We haven’t tried to quantify these costs, and ignore donations in kind in the rest of the estimates.

Now, let’s compare these costs to our historical impact.

Value of top plan changes

The main way we estimate our impact is to try to identify the highest-impact plan changes we’ve caused, write up detailed case studies about them, quantify their value, and seek external estimates to cross-check against our own.

Since we think the majority of our impact comes from a small number of the highest-impact plan changes, this captures a good fraction of the total.

Examples of top plan changes

You can see some examples of top plan changes from previous years here:

- 5 examples of new plan changes recorded in 2016.

- Other examples of high-impact plan changes over our history, released in 2016.

- 27 studies of plan changes, released 2015 and now quite out of date.

Unfortunately, many of the details of the plan changes can’t be shared publicly due to confidentiality. If you’re considering donating over $100,000, we can share more details if you email [email protected].

How to quantify the value of top plan changes in donor dollars

One way we try to quantify the value of the plan changes is in “donor dollars” i.e. the value of a dollar to the next best place our donors could have donated otherwise at the current margin. To be more concrete, most of our funding would have gone to opportunities similar to those funded by the EA Community and Long-term funds.

This means that one way to quantify the value of the changes is to imagine the plan change never happened, but instead X additional dollars were given to the EA community or Long-term Fund. Then, we need to try to estimate of the value of X where this option is equally as good as the actual world in which the plan change did happen.

Our aim is to make an all-considered tradeoff, taking account of:

- The counterfactual – the chance that the person changed their plans anyway.

- Discounting – resources are worth less if they come in the future.

- Opportunity costs – the value of what the person would have done if they hadn’t made the change.

- Drop out – the chance that the person doesn’t follow through with their plan change.

Needless to say, this is extremely hard, but we need to try our best.

Another problem with the donor dollar metric is that additional money has diminishing returns, and other non-linearities, which means that summing the value of different plan changes can be misleading. It will also change from year-to-year as funding constraints vary, so we need to update our estimates each year.

This definition made, the question is whether each dollar of resources we’ve used has created more than one additional donor dollar of value.

What’s the value of the top plan changes in donor dollars?

We created a new list of our top 10 plan changes of all time, and made our own dollar estimates of their value, using the method above. In particular, we drew heavily on the figures provided in the 2017 talent survey by about 30 leaders in the effective altruism community.

In most cases, we also asked at least two people outside of 80,000 Hours to make their own estimates (ideally people who are familiar with the relevant area). We combined the estimates, arriving at the following results.

These results are only useful if you’re relatively aligned with us in choice of problem area, epistemology and the degree of talent-constraint in these areas.4 If you’re interested in donating to us, you might want to make your own estimates, and we can provide more details if you email [email protected].

Having said that, we have examples of plan changes of many different types (e.g. across global poverty and animal welfare as well as extinction risks), so even if you’re not fully aligned with us, 80,000 Hours can still be impactful.

Here are our estimates of the value of the top ten plan changes in donor dollars:

| Number | Best guess net present value in donor dollars | Bottom 10% confidence interval | Top 10% confidence interval | "Realised" value | Percentage realised | First recorded | Change this year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20,000,000 | 700,000 | 60,000,000 | 7,500,000 | 38% | 2016 | Major upgrade |

| 2 | 3,000,000 | -300,000 | 20,000,000 | 300,000 | 10% | 2014 | None |

| 3 | 2,500,000 | 0 | 10,000,000 | 43,000 | 2% | 2014 | None |

| 4 | 2,000,000 | 100,000 | 20,000,000 | 666,667 | 33% | 2016 | Upgrade |

| 5 | 2,000,000 | 200,000 | 10,000,000 | 500,000 | 25% | 2014 | Upgrade |

| 6 | 1,600,000 | 500,000 | 4,000,000 | 30,000 | 2% | 2014 | None |

| 7 | 1,100,000 | 200,000 | 8,000,000 | 100000 | 9% | 2015 | None |

| 8 | 1,000,000 | 0 | 10,000,000 | 0 | 0% | 2016 | None |

| 9 | 1,000,000 | 0 | 10,000,000 | 100,000 | 10% | 2016 | None |

| 10 | 1,000,000 | -200,000 | 5,000,000 | 1,000,000 | 100% | 2014 | None |

| TOTAL | 35,200,000 | 1,200,000 | 157,000,000 | 10,239,667 | 29% |

Plan change value is “realised” when the person contributes labour or money to a top problem area.

If we take these figures at face value, and sum them, then their total value is about $35m, 18.5 times higher than our financial costs, and 6.1 times higher than total costs including opportunity costs of $5.8m.

Note again that since most meta-charities don’t include opportunity costs in their multiplier estimates, you should use the higher figure if making a side-by-side comparison.

Value of plan changes outside of the top 10

We’ve recorded over 3,200 significant plan changes in total, so this estimate only considers 0.3% of the total. What might the value of the rest be?

We’ve recorded a further 90 plan changes rated 10. We think these have an average value of about $100,000, making for a further $9m.

Another 1,500 were rated 1. We took a random sample of 10 and made estimates, giving an average of $7,000, adding up to another $10.5m.

Another 1,600 were rated 0.1, which we think are worth about 10% as much, adding up to another $1.05m.

We also need to consider the value of plan changes we haven’t tracked, those that will be caused in the future due to our past efforts, and also those who made worse decisions as a result of engaging with us, but we’ve left these out for now. We’ll discuss some ways we might have a negative impact in a later section.

Putting these together:

| Best guess net present value summed in donor dollars | Percentage of total | |

|---|---|---|

| Top 1 | 20,000,000 | 36% |

| Next 9 | 15,200,000 | 27% |

| 90 more plan changes rated 10 | 9,000,000 | 16% |

| 1,500 plan changes rated 1 | 10,500,000 | 19% |

| 1,600 plan changes rated 0.1 | 1,120,000 | 2% |

| Untracked plan changes | ??? | |

| Future plan changes resulting from past activity | ??? | |

| Negative value plan changes | ??? | |

| Total | 55,820,000 | 100% |

The sum of $55.8m is 29.3 times higher than financial costs, and 9.6 times higher if we also add opportunity costs.

There is a great deal to dispute about these estimates, but they provide some evidence that 80,000 Hours has been a highly effective use of resources so far.

We can also try to increase the robustness of these estimates by comparing them to some different methods, which is what we’ll cover next.

Increasing the capacity of the effective altruism community

Another way 80,000 Hours has an impact is by introducing people to the ideas of effective altruism, and helping them get involved with the community. If you think building effective altruism community is valuable, this could be a large source of impact, which is also somewhat independent from the direct value of the plan changes as covered above.

We argued earlier that plausibly 5-15% of the current membership of the community can be attributed to 80,000 Hours. We can then multiply this by the total value of the community to make an estimate of our impact.

For the value of the community, we’d encourage you to make your own estimate. Our own (not at all robust) estimate is that the present value of the community is over $1bn donor dollars, with an 80% range of at least $100m – $10bn (even if we completely exclude Open Philanthropy). One reason we think it’s this high is because it seems likely that the community will raise at least a present value of $1bn in extra donations for effective altruism causes in the future by attracting a couple more HNW donors, or simply through the Giving What We Can pledge (which has already raised over $1bn of commitments), and we think the community will achieve much more than just raise money.

If the present value of the community is over $1bn, then 5-15% of that would be worth $50-$150m, or 8-26 times our total financial and opportunity costs.

To make a full estimate, however, we’d also need to consider negative effects 80,000 Hours might have had on the community. For instance, we might have made the community less welcoming by focusing on a narrow range of careers and causes, putting off people who would have otherwise become involved. Some have also argued that growing the number of people in the community can have negative effects since it makes coordination harder. We cover more ways we might have had a negative impact later.

Acting as a multiplier on the effective altruism community

Besides growing the capacity of the community, 80,000 Hours is also the main source of research on career choice that the community uses. If this research is useful, then it can make people in the community more effective.

If, as above, we think the community will have over $1bn of impact in donor dollars, and we’ve used $5.8m of resources, then we’d only need to increase the effectiveness of how these resources are used by 5.8/1000 = 0.58% to justify our costs.

In practice, we think 80,000 Hours has quite major impacts on the community, such as:

- Encouraging the idea that effective altruism should be about how to spend your time rather than only your money, and presenting evidence that talent gaps are more pressing than funding gaps.

- Helping to focus the community more on the long-term future and animal welfare rather than only global poverty, and helping to make AI technical / strategy / policy / support commonly considered career options in the community.

- Several other organisations have adopted our organisational practices. For instance, the plan change metric has been adopted by CFAR and considered by others; and we helped CEA enter Y Combinator and develop a more startup style strategy

Though, as in the previous estimate, we’d also need to subtract potential negative impacts.

Impact from Giving What We Can pledges

A minor way we have an impact is by encouraging people to take the Giving What We Can pledge and donate more to effective charities. We can use this to get a lower bound on our impact, especially if you’re more concerned by global poverty. We covered this method in more depth last year.

Over our entire history, we’ve encouraged 318 people to take the pledge, who say they likely wouldn’t have taken it without 80,000 Hours.

In Giving What We Can’s most recent published report, from 2015, they estimated that each person who takes the pledge donates an extra $60,000 to top charities (NPV, counterfactually and dropout adjusted). Note that we expect about 30% of this to go to long-term and meta charities, 10% animal welfare and 60% global poverty, so the units are not the same as the donor dollars earlier.

We think the $60,000 estimate might be a little high for new members, but even if we reduce it to $20,000, that’s $6.4m of extra donations to top charities.

This would be about 3 times our financial costs, and about equal to total costs including opportunity costs.

Marginal cost-effectiveness

If you’re considering donating to or working at 80,000 Hours, then what matters is the cost-effectiveness of future investment (at the margin), rather than what happened in the past. Historical cost-effectiveness is some guide to this, but it could easily diverge.

You’d then compare this cost-effectiveness to “the bar” for investment by the community, but we don’t do this here.

Unfortunately, estimating marginal cost-effectiveness is even harder than estimating historical, but below we cover several ways to go about it.

First, we’ll consider what our prior should be, then a “top down” method estimating our growth rate, then a “bottom up” method based on our recent activities, and then suggest a long-term growth oriented approach at the end.

Should we expect marginal cost-effectiveness to increase or decrease?

It’s often assumed that our cost-effectiveness ratio should decline over time, due to diminishing returns.

This is true in the long-term, however, over shorter time scales opposing effects can dominate, such as economies of scale and learning: over time we become better and better at causing plan changes with the same amount of resources.

Our expectation is that learning effects will continue to dominate over the next 1-3 years, decreasing the cost per plan change. Although we have taken some low hanging fruit (e.g. promoting some of the best paths we know about), we still see ways to become much more efficient. For instance, despite little increase in our number of staff, we’ve tripled our web traffic in three years — this roughly means that each piece of new content gets 3-times as many views as it did in the past, making work on content about 3-times more effective than in the past. We’ve also become quicker and better at writing, and we expect we can continue to improve. We cover more ways to improve efficiency in the plans section later.

Another difficulty is that much of our resources go into “investment” that we expect will continue to pay off many years in the future (e.g. we improve our research, grow our baseline traffic, train the team). Since these future plan changes have not been included in our impact estimates, they will increase our cost-effectiveness when they arrive in the future.

One consequence of this is that if we ramp up investment spending (as we did this year), it should temporarily drive down our cost-effectiveness ratio, but this shouldn’t be confused for a decrease in actual cost-effectiveness.

Top down: increase in total plan change value

These caveats in mind, one way to make a quantitative estimate of marginal cost-effectiveness is to compare our impact at the end of 2016 to our impact now, and then compare that to our increase in total costs.

Unfortunately, we didn’t make estimates using the same methods at the end of 2016, so we can’t make a side-by-side comparison. However, there are a couple of ways we can make a rough estimate.

One method is to put a dollar value on the different types of plan change (0.1/1/10/100/1000), assume they’re constant, and then compare the summed totals then and now:

| End of 2016 | End Nov 2017 | Growth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of plan changes number rated 1 | 866 | 1,498 | 73% |

| Average value of plan changes rated 1 | 7,000 | 7,000 | |

| Total number of plan changes rated 10 | 42 | 89 | 112% |

| Average value of plan changes rated 10/$ | 100,000 | 100,000 | |

| Total number of plan changes rated 100 | 7 | 9 | 29% |

| Average value of plan changes rated 100 | 1,600,000 | 1,600,000 | |

| Total number of plan changes rated 1000 | 0 | 1 | NA |

| Average value of plan changes rated 1000 | 20,000,000 | 20,000,000 | |

| Summed value in donor dollars | 21,462,000 | 53,786,000 | 151% |

| Total financial and opportunity costs/$ | 4,093,747 | 5,810,680 | 42% |

| Ratio | 5.2 | 9.3 |

This method suggests that our cost-effectiveness went up by almost a factor of 2 in 2017, though the increase is small compared to uncertainty in the estimate.

Moreover, much of the increase was due to adding one plan change rated 1000 in 2017. If we exclude this, the ratio was flat.

One complication is that many of the plan changes we recorded in 2017 were due to activities before 2017 (which would decrease the effectiveness in 2017). On the other hand, much of our spending in 2017 will produce plan changes in 2018 and beyond, and this would increase the estimate if included. It’s unclear which effect dominates.

Another way to make an estimate of our change in total impact is to look at changes in the top 10 list, since they account for about 60% of the value measured in donor dollars.

| Number | Best guess net present value in donor dollars | First recorded | Change this year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20,000,000 | 2016 | Major upgrade |

| 2 | 3,000,000 | 2014 | None |

| 3 | 2,500,000 | 2014 | None |

| 4 | 2,000,000 | 2016 | Upgrade |

| 5 | 2,000,000 | 2014 | Upgrade |

| 6 | 1,600,000 | 2014 | None |

| 7 | 1,100,000 | 2015 | None |

| 8 | 1,000,000 | 2016 | None |

| 9 | 1,000,000 | 2016 | None |

| 10 | 1,000,000 | 2014 | None |

| SUM | 35,200,000 |

Our estimate is that the plan change rated 1000 would have been valued at more like $3m in 2016, so it saw a $17m increase, or about 50% of the total.

However, even if we put this to one side and focus on the other nine, two of the plan changes were new, and two more were upgraded. That means that in 2016 there were about 5 plan changes valued at over $1m, whereas now there are 9. That’s an increase of 1.8-fold, roughly matching our other estimate of a 2-fold increase.

“Bottom up” estimate of recent activities

One weakness of the top down approach is that the nature of our activities and plan changes have changed over time. In particular, some of our most valuable plan changes in the past were caused by research and networking that we might not be able to repeat going forward, or won’t be aided by marginal donations.

So, an approach that might be more relevant to donors is to make a “bottom up” estimate of the cost-effectiveness of our marginal activities.

In the earlier section on our upgrading process, we estimated that in the last few months it has produced plan changes rated 10 within 18 months for about $8,100. We also think this process can be scaled at the margin, and likely made more efficient, and this ignores all our other forms of impact.

If we add opportunity costs at the 2017 ratio, that would be $42,000 per rated-10+ plan change.

The question then becomes whether recent plan changes rated 10 are worth this many donor dollars.

We tried to identify the top plan changes that were newly recorded in 2017. We excluded one that was due to networking, so doesn’t obviously reflect the impact of scalable activities. We made donor dollar estimates of the remainder, using the same process as above, finding a total value of just under $3m.

Given that there were 49 new rated-10 plan changes in total over 2017, that would imply their mean value is at least $60,000.

We also estimated that the lowest value plan change was worth about $50,000. Roughly, we can add this to the contribution from the top 8 plan changes, and estimate the mean is about $110,000.

$110,000 per rated-10 plan change is about 13.6-times higher than financial costs, and 2.6-times higher if opportunity costs are also included.

This is a little lower than our previous estimates, but is likely an underestimate, since the value of the plan changes tends to increase over time as we gain more information.

The growth approach to evaluating startup nonprofits

A final approach to estimating marginal cost-effectiveness would be to focus more on future benefits, rather than our 2017 impact.

We intend for the vast majority of the impact of 80,000 Hours to lie in the future. The methods above, however, only consider “banked” plan changes, leading to too much focus on the short-term. It’s like evaluating a startup company based on its current profits, when what actually matters is long-term return on investment.

Estimating cost-effectiveness based on future growth, however, is also very hard. We suggest some rules of thumb in this more in-depth article on the topic.

One way you could approach the estimate is to think about the total value 80,000 Hours will create if it succeeds in a big way, and then consider how marginal investment changes the chance of this happening, or brings forward this impact.

We think the potential upside of 80,000 Hours is high. For instance, if we can engage 5% of talented young people, then about 5% of political, business, and scientific leadership will have been readers, and this is a group that will influence hundreds of billions of dollars of resources per year in the US alone.

If you think there’s some non-tiny probability of this kind of scenario, then it’ll be highly effective to fund 80,000 Hours to a level that lets us grow at the maximum sustainable rate, bringing this impact as early as possible.

Mistakes and issues

The following are some mistakes we think we’ve made which became clear this year. We also list some problems we faced, even if we’re not sure they were mistakes at the time.

People misunderstand our views on career capital

In the main career guide, we promote the idea of gaining “career capital” early in your career. This has led to some engaged users to focus on options like consulting, software engineering, and tech entrepreneurship, when actually we think these are rarely the best early career options if you’re focused on our top problems areas. Instead, it seems like most people should focus on entering a priority path directly, or perhaps go to graduate school.

We think there are several misunderstandings going on:

- There’s a difference between narrow and flexible career capital. Narrow career capital is useful for a small number of paths, while flexible career capital is useful in a large number. If you’re focused on our top problem areas, narrow career capital in those areas is usually more useful than flexible career capital. Consulting provides flexible career capital, which means it’s not top overall unless you’re very uncertain about what to aim for.

You can get good career capital in positions with high immediate impact (especially problem-area specific career capital), including most of those we recommend.

Discount rates on aligned-talent are quite high in some of the priority paths, and seem to have increased, making career capital less valuable.

However, from our career guide article, some people get the impression that they should focus on consulting and similar options early in their careers. This is because we put too much emphasis on flexibility, and not enough on building the career capital that’s needed in the most pressing problem areas.

We also enhanced this impression by listing consulting and tech entrepreneurship at the top of our ranking of careers on this page (now changed), and they still come up highly in the quiz. People also seem to think that tech entrepreneurship is a better option for direct impact than we normally do.

To address this problem, we plan to write an article in January clarifying our position, and then rewrite the main guide article later in the year. We’d also like to update the quiz, but it’s lower priority.

We’ve had similar problems in the past with people misunderstanding our views on earning to give and replaceability. To some extent we think being misunderstood is an unavoidable negative consequence of trying to spread complex ideas in a mass format – we list it in our risks section below. This risk also makes us more keen on “high-fidelity” in-person engagement and long format content, rather than sharable but simplified articles.

Not prioritising diversity highly enough

Diversity is important to 80,000 Hours because we want to be able to appeal to a wide range of people in our hiring, among users of our advice, and in our community. We want as many talented people as possible working on solving the world’s problems. A lack of diversity can easily become self-reinforcing, and if we get stuck in a narrow demographic, we’ll miss lots of great people.

Our community has a significant tilt towards white men. Our team started with only white men, and has remained even more imbalanced than our community.

We first flagged lack of team diversity as a problem in our 2014 annual review, and since then we’ve taken some steps to improve diversity, such as to:

- Make a greater effort to source candidates from underrepresented groups, and to use trial work to evaluate candidates, rather than interviews, which are more biased.

- Ask for advice from experts and community members.

- Add examples from underrepresented groups to our online advice.

- Get feedback on and reflect on ways to make our team culture more welcoming, and give each other feedback on the effect of our actions in this area.

- Put additional priority on writing about career areas which are over 45% female among our target age ranges, such as biomedical research, psychology research, nursing, allied health, executive search, marketing, nonprofits, and policy careers.

- During our next round of board reform, we’ve found a highly qualified woman who we have asked to join.

- Do standardised performance reviews, make salaries transparent within the team, and set them using a formula to reduce bias and barriers.

- Have “any time” work hours and make it easy to remote work.

- Implement standard HR policies to protect against discrimination and harassment. We adopted CEA’s paid maternity/paternity leave policy, which is generous by US standards.

Our parent organisation, CEA, has two staff members who work on diversity and other community issues. We’ve asked for their advice, and supported their efforts to exclude bad actors, and signed up to their statement of community values.

However, in this time, we’ve made little progress on results. In 2014, the full-time core team contained 3 white men, and now we have 7. The diversity of our freelancers, however, has improved. We now have about 9 freelancers, of which about half are women, and two are from minority backgrounds.

So, we intend to make diversity a greater priority over 2018.